I’ve looked at Melbourne residential density in detail, so what about other Australian cities? Is population weighted density a useful measure? Does population weighted density help explain differences in public transport mode shares?

For this exercise, I’ve looked at 2011 census data at the Statistical Area Level 1 (SA1) geography (currently the smallest geography for which population data is available) for Greater Capital City Statistical Areas (which include large tracts of rural hinterland). I’ve sometimes applied an arbitrary threshold of 3 persons per hectare to define urban residential areas.

Measures of overall density

Population weighted density is a weighted average of the density of all the parcels of land in the city, with the population of each parcel of land providing the weighting. This provides a figure indicative of the residential density of the “average person”, although that’s still a little abstract. A city where a large proportion of people live in dense areas will have a much higher weighted population density than average population density.

Average density is simply the total population divided by the area of the city (or if you like, the average density weighted by the areas of each parcel of land). In calculating average residential density (which I’m doing in this post), the area would only include residential areas (I’ve arbitrarily used a threshold of SA1s with at least 3 persons per hectare).

Another measure is urban density, which considers all the land that makes up the urban city, including non-residential areas, but excluding the rural land that makes up large parts of most metropolitan areas when defined by administrative boundaries. I have not attempted to measure ‘urban’ density in this post.

Firstly here’s a table of data for the six largest Australian cities with three different measures of 2011 residential density:

| Greater Capital City Statistical Area |

Pop |

Pop (>3/ha) |

Area, square km (>3/ha) |

Pop-weighted density, persons/ ha (all SA1s) |

Pop-weighted density, persons/ ha (SA1s >3/ha) |

Average residential density, persons/ ha (SA1s >3/ha) |

| Greater Sydney |

4391578 |

4225278 |

1530 |

50.2 |

52.1 |

27.6 |

| Greater Melbourne |

3999924 |

3832366 |

1812 |

31.8 |

33.1 |

21.1 |

| Greater Brisbane |

2066134 |

1866794 |

1127 |

22.6 |

24.8 |

16.6 |

| Greater Perth |

1728567 |

1639849 |

963 |

21.6 |

22.7 |

17.0 |

| Greater Adelaide |

1225136 |

1161668 |

644 |

21.2 |

22.3 |

18.0 |

| Australian Capital Territory |

356563 |

350917 |

221 |

20.5 |

20.8 |

15.9 |

You’ll notice that Melbourne has a lower population than Sydney, but the total land area above 3 persons/ha is much larger.

Here are those densities in chart form:

You can see Sydney has around double the population weighted density of most other cities, but its average density is only about 60% higher. These figures show Sydney has a very different density pattern compared other Australian cities.

You can also see very little difference in weighted density whether you exclude low density land parcels or not (the blue and red bars). The density is brought down only slightly by the relatively small number of people living in very low density areas (below 3 persons/ha) within the statistical geography. Thus weighted average density is a good way to get around arguments about the boundary of the “urban” area. But then we are only measuring residential density here – and the large unoccupied spaces between residents of a city are very important when it comes to transport issues.

Can you compare population weighted density of Australian cities with international cities? Yes, but only if the parcels of land used are of a similar size and created in a similar fashion. The more fine-grained the geography (ie smaller the parcels of land), the more non-residential pockets of land will be excluded from the calculation. Anyone doing an international comparison should compare how the ABS create their geography at SA1 level with approaches of other statistical agencies. And please comment below if you get a set of comparable figures.

Density by distance from the CBD

The differences in density can be seen a little more clearly when you look at weighted average density by distance from the city centre:

(note: I’ve chopped the vertical scale at 100 persons/ha so parts of central Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane are off the scale).

For Perth, Adelaide, Brisbane and Canberra (ACT) you can see a weighted average density in the mid to low 20s for large areas of the city, indicating large tracts of what you might describe as traditional Australian suburbia. In Canberra this kicks in at just 2 km from the CBD, and in Adelaide it kicks in 3 km from the city.

In Melbourne the weighted average density doesn’t get below 30 until 9 kms from the CBD indicating a larger denser inner area, and in Sydney it doesn’t drop below 30 until you are 39 km from the CBD!

Distribution of population at different densities

Here’s a frequency distribution of densities in the cities:

I’m using an interval of 1 person/ha, and the figures are rounded down to form the values on the X axis (ie: the value you see at 20 persons/ha is the proportion of the population living between 20 and 21 persons/ha).

You can see Sydney has the flattest distribution of all – indicating it has the widest range of densities of any city. Melbourne is not far behind, whereas Canberra has a lot of people living in areas between 12 and 24 persons/ha.

Note that many cities have a significant proportion of the population living at rural densities (0 to 1 person per hectare), particularly Greater Brisbane.

Another way to look at this data is a cumulative frequency distribution:

You can read off the median densities for the cities: Sydney 33, Melbourne 28, Brisbane 22, Perth 22, Adelaide 22, Canberra 19.

You can also see that 30% of people in Sydney live in densities of 44 persons/ha or more – compared to only 12% of Melburnians, 5% of Brisbanites, and less than 2% of people in the other cities.

If 15-30 persons per hectare is what you define as suburbia, then that’s 26% of Sydney, 37% of Melbourne, 44% of Brisbane, 55% of Perth, 57% of Canberra and 62% of Adelaide.

Spatial distribution of density

For the purest view of density you cannot get past a map. The following maps show a simple density calculation at the SA1 geography.

Update 22 Oct 2012: maps now include railway lines using OpenStreetMap data provided by Maps Without Borders. The data is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0, copyright OpenStreetMap and contributors.

Sydney

You can see vast areas of darker green (40+/ha), particularly between Sydney Harbour and Botany Bay. There are also quite a few green areas in the western suburbs, while the northern north shore has the lowest density. There are many concentrations of density around the passenger rail lines.

Melbourne (and Geelong)

You can see areas of dark green around the inner city, with large tracts of yellow and green in the suburbs (25-35 persons/ha). There are however areas of moderate green (30-40) in some of the newer outer growth areas to the west and north, reflecting recent planning. There’s a not a strong relationship to train lines, but this might reflect higher densities equally attracted to tram lines (not shown on the map).

Note this map is slightly different to that in a recent post where I masked out non-residential mesh blocks.

Brisbane

You can see dark green patches around the river/CBD, but then mostly medium to low densities in the suburbs. There’s very little evidence of higher densities in fringe growth areas. There are some denser areas around railway lines (note the map does not show Brisbane’s busway network).

Perth

You can see green patches around the city, but also in some fringe growth areas where new planning controls are presumably forcing up densities. There are however vast tracts of orange (15-25 persons/ha), and little evidence of higher density around the rail lines (note: a lot of the lines are freight only and the north-south passenger line has very broad station spacing and limited walking catchment as most of it is within a freeway median).

Adelaide

Adelaide some inner city blocks of high density, but once you get outside the green belt surrounding the city blocks, you fairly quickly head into suburban densities. There are only a few pockets of high density in the middle and outer suburbs, and very little relationship evident between density and the rail lines.

Canberra (and Queanbeyan)

Canberra has vast areas at low density, and only a few pockets with dark green. There are however green patches on the fringes (particularly in the far north and far south), perhaps again reflecting planning policies forcing up densities.

Sydney is really quite a different city compared to the rest of Australia, with a much larger share of the population living in high density residential areas (more than I had expected). Melbourne has a much lower population weighted density (still quite a few people living in high density areas, but much less so than Sydney), followed by four cities that aren’t that different when it comes to density: Brisbane, Perth, Adelaide and Canberra.

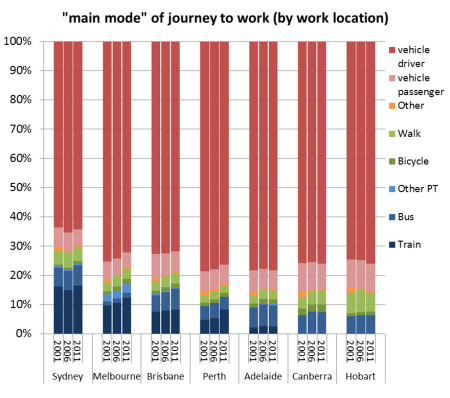

What about density and public transport use?

Here’s a comparison of density (measured as both average and population weighted) and the most recent estimate of public transport mode share of motorised passenger kms for Australian cities:

Population weighted density certainly shows a stronger relationship with public transport use than average density (r-squared of 0.89 versus 0.82 on a linear regression).

If you believe that higher population density will lead to higher public transport use (for a given level of public transport service), then you would expect Sydney to be well placed to have a higher public transport mode share. Which indeed it does, but does it have the same level of public transport supply as other cities, and are all other factors equal? That’s a very difficult question to answer.

You could measure public transport service kilometres per capita, but different modes have different speeds, stopping frequencies and capacities, public transport supply will vary greatly across the city, and some cities might have more effective service network designs that others.

If all cities had the same levels of public transport supply and all other things were equal, you might expect a straight line relationship (or perhaps an exponential relationship). But Brisbane and Melbourne (and to a small extent Perth) seem to be bucking what otherwise might be a linear pattern. Are these cities doing much better with quality and quantity of public transport supply? Or is it something else about those cities?

Car ownership rates do vary between Australian cities, but this might be more a product of public transport viability for particular residents:

Also, we know that car ownership doesn’t have a strong relationship with car use.

When working population census data comes out I would like to look at the distribution of employment within cities. We know that public transport use is highest for journeys to work in the CBD (as it usually competes strongly against the car), so the proportion of a city’s jobs that are in the CBD is likely to impact the public transport mode share (at least for journeys to work). Moreover, a higher average employment density in general might be easier to serve with competitive public transport, and thus lead to a higher public transport mode share. It will hopefully also be possible to calculate weighted density of employment (at least at the SA2 level).

Finally, I’d like thank Alan Davies (The Urbanist) for inspiring this post.

Other posts about density:

Posted by chrisloader

Posted by chrisloader