[updated 12 January 2015]

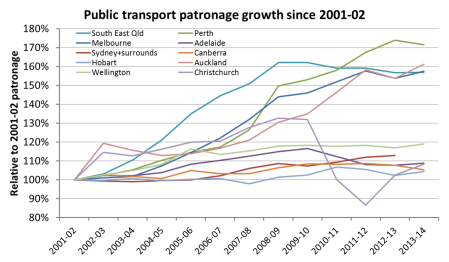

With some effort and assistance from others, I’ve managed to compile public transport patronage data for major cities in Australia and New Zealand. What follows are trends on what I do have, including figures for 2013-14 for most cities.

A large number of caveats are required around the data (particularly Sydney). I have used South East Queensland (the TransLink service area) and what I am calling Sydney and surrounds (the catchment for CityRail including Sydney, Newcastle/Hunter, and Wollongong/Illawarra). See below for full details.

Overall Patronage growth

This chart shows growth in patronage since 2001-02 (an arbitrary start year).

Observations:

- Several cities have shown very strong growth:

- In Perth part of this can be attributed to the opening of the Mandurah rail line in late 2007.

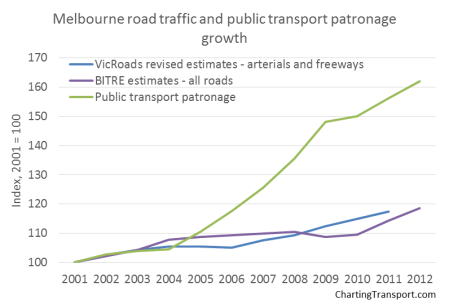

- Melbourne saw strong patronage growth between 2004 and 2011, with a particularly big jump in 2008-09.

- South East Queensland invested in bus services between 2003 and 2009, including radial busways to the Brisbane CBD. However patronage peaked in 2009-10, and has been flat or declining since. This may be impacted by the floods and associated free travel periods (not counted as patronage), and recent above-CPI fare price rises. Also train patronage under the old paper ticketing system may have been overestimated – creating an inconsistency in the time series as people transition to Go Card.

- Auckland and Christchurch had very strong growth to a peak in 2002-03 (attributed by some to a boom in international students), a lull and then strong growth again from 2007. Christchurch patronage fell dramatically in 2010-11 following a major earthquake that closed large parts of the CBD (where PT probably had a high mode share) and led to population decline.

- The other cities are languishing significantly behind:

- Sydney’s problems with public transport are often discussed, and I understand there has been relatively little expansion in services in recent years. Some modest growth is evident from 2010 onwards. It is very difficult to obtain Sydney bus patronage data, and I do not have a 2013-14 data point.

- Adelaide has not been investing significantly in bus or train services in recent years (although that is now changing). Patronage peaked in 2009-10. The completion of recent rail upgrades may see rises in the coming years.

- Canberra has seen both funding cuts and increases over the years.

- Hobart is included for completeness. I cannot comment on reasons for patronage trends there. Their annual report does.

- Wellington has also had only modest patronage growth, although it maintains the strongest rate of public transport use in New Zealand.

Note:

- Greater Sydney data is very difficult to obtain – mostly because private bus, ferry and light rail data is not published in any consistent form. In the above I have used a dataset prepared by BITRE and data published by the NSW Bureau of Transport Statistics.

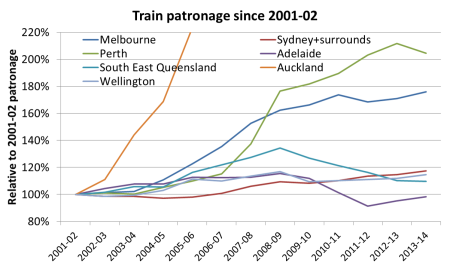

Train patronage

- Auckland train patronage growth is off the chart. 2013-14 patronage was around 508% higher than 2001-02 patronage, following 10 consecutive years of annual growth above 10% (there was actually a decline in patronage in 2012-13 of 8.3% but growth rebounded in 2013-14 to 14.4%). Auckland has been heavily investing in services, a new city terminal, and electrification. Patronage growth is off a very small base, such that percentage growth rates are very large.

- You can see the significant surge in Perth train patronage following the opening of the Mandurah line in late 2007. Patronage has more than doubled in 10 years, although curiously declined in 2013-14.

- Melbourne saw a steady increase in train patronage between 2005 and 2011, an easing in 2011-12, but further growth since then.

- South East Queensland train patronage figures dropped after 2009. TransLink make a comment about a change of ticketing system impacting these figures in their tracker report (previous estimates probably being inflated), so it is unclear what the “real” trend is.

- Adelaide train patronage dropped until 2012 as lines closed for extended periods to enable electrification works. Lines have reopened and electric services are running, with a bounce in patronage evident from 2012.

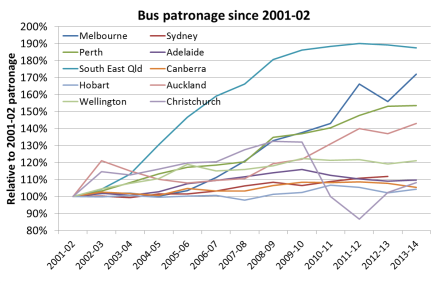

Bus patronage

- South East Queensland is by far the standout for bus patronage growth, which has followed substantial investment in busways and increases in bus frequency. Patronage almost doubled to 2012 on SEQ buses, although there has been a decline post 2012.

- Melbourne’s bus patronage has grown significantly since 2006-07 onwards, although with a difficult to explain spike in 2011-12.

- Perth’s bus patronage is an interesting story. Between 2007-08 and 2009-10, patronage increased by 14%, while timetabled kms only increased by 2.8%. When the Mandurah line was opened in late 2007, buses that previously travelled into the city were converted into rail feeder buses. This significantly reduced the bus trip lengths and hence passenger trip lengths for people who now transfer onto trains (the introduction of transfers might also have increased total boardings more than the total number of “journeys”). Presumably it meant that bus frequencies could be improved and/or buses were reconfigured to meet travel demands that were not well catered for previously.

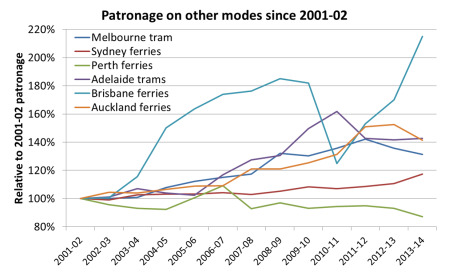

Ferry and light rail patronage

- Brisbane ferry patronage almost doubled between 2002-03 and 2008-09, collapsed in 2010-11 following service suspensions and cutbacks resulting from flood damage, and then bounced back from 2011 and is growing stronger still. The strong growth to 2008-09 followed increased services, and fare integration with other modes.

- Adelaide tram patronage grew significantly following the tram extensions into the city that opened in 2007 and 2010 (travel within the CBD area being free). For reasons better known to others, Adelaide tram patronage has declined since 2011.

- Sydney ferry patronage has been mostly flat until 2013 (note: at the time of writing I did not have a good estimate of private ferry patronage (approx 9% of all ferry patronage) – from 2009-10 onwards I have simply assumed no change in those numbers for want of something better).

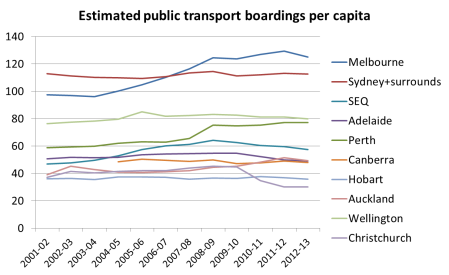

Boardings per capita

Trends in public transport patronage will of course be impacted by population growth, so the ratio of the two can be a good indicator of system performance.

However, it is not necessarily fair to compare cities. The Sydney transit area includes many urban areas significantly detached from the main Sydney metropolitan area, including the cities of Newcastle and Wollongong. South East Queensland includes the Gold and Sunshine Coasts. But the Melbourne catchment does not include Victoria’s equivalent city of Geelong. The boardings per capita figure for the main Sydney and Brisbane metropolitan areas would likely be higher than the figures here. So it is more important to look at trends (household travel survey mode share figures may be a better method of comparison).

- This chart shows Melbourne as the stand-out in terms of increasing boardings per capita, a trend that started in 2004-05 (as many other of my posts have shown), although with some decline in 2012-13.

- South East Queensland showed an increasing trend between around 2003-04 and 2008-09 but has since been in decline.

- Perth had a significant increase in 2008-09, following the opening of the Mandurah rail line.

- Adelaide has declined in recent years (in part due to rail works) while Canberra and Hobart remain flat.

- Sydney+surrounds has bucked the trend of the larger cities, with no great increase in boardings per capita.

- Wellington has the highest boardings per capita in New Zealand (notionally higher than most Australian cities). When you take into account that Wellington does not have a heavily transfer-orientated PT network, a figure for PT “journeys” per capita for Wellington is likely to be very competitive with Melbourne and Sydney.

- Auckland has seen some steady growth in recent years from a low base.

- Christchurch had seen some small growth to 2009-10, but collapsed in 2010-11, after major earthquake disruptions in the city. They appear to have arrested the decline in 2012-13.

Again, I must stress that it is dangerous to read too much into comparisons between cities because of the somewhat arbitrary definitions of transit system area boundaries.

For New Zealand, I have used “service area population” estimates kindly provided to me by Ian Wallis and Associates (for up to 2009-10) and then applied district population growth rates to estimate 2010-11 (and subsequent) service area populations.

A slightly better measure than public transport boardings per capita might be public transport journeys (or linked trips) per capita. This is something I would like to explore more in a future post.

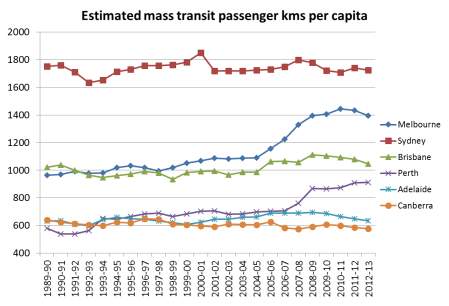

The BITRE yearbook includes data on passenger kms per mode per city. From this data it is possible to obtain estimates of mass transit passenger kms per capita (I say mass transit, as they do not distinguish public and private bus). Here’s a chart using the 2014 yearbook data:

The trends are not dissimilar to my chart above. The BITRE figures are presumably a multiplication of estimated boardings (very similar data to mine) by estimated average route length (I suspect highly accurate time series, data on this is hard to find), or similar.

Long term patronage data

David Cosgrove from BITRE recently collated annual data on public transport patronage for all Australian capital cities, right back to 1900. His very interesting ATRF 2011 paper is here. He includes several summary charts which I won’t repeat here. What follows is some further analysis of this particular dataset.

The following chart shows estimated public transport trips per capita over 110 years:

Note BITRE used Sydney statistical division population with all Cityrail patronage, which is different to my approach above. It probably explains why Sydney figures are much higher.

Public transport usage rates grew until Word War 1, dropped in the Great Depression, peaked during petrol rationing in World War 2, and then declined until around 1980. In the bottom right corner you can see several cities trending upwards in recent times.

It is interesting to see Canberra had comparatively very low rates of public transport use until the 1980s – perhaps the product a low density car-based city from the start? Although public transport was clearly important leading up to Word War 2.

The Darwin figures are even lower – I’m not sure of the history but perhaps Darwin only became big enough to need public transport in the 1950s, a time when the car was becoming widely affordable.

You can see a spike in Hobart PT use from 1975 to 1977 – when the Tasman Bridge connecting the two sides of the city was severed after being struck by a ship.

The paper also includes estimates of passenger kms by mode since 1945. Here is a chart showing public transport mode share of motorised passenger kms:

Again I think the Sydney figures are inflated by non-Sydney Cityrail patronage.

More BITRE analysis is available in this 2014 paper.

Caveats and Disclaimers

This stuff is important, particularly for Sydney figures. (Similar caveats would apply to the long-term data from BITRE immediately above)

- Patronage is invariably an estimation exercise, as not all passengers buy or validate a ticket when they board. The methodology used by agencies probably varies quite a bit. For example, Translink don’t seem to estimate free trips. The figures I have presented however are estimates of boardings (including boardings on journeys involving transfers). As far as I am aware, they include school children travelling on government funded bus services.

- I have adjusted official Melbourne bus patronage figures to account for a change in estimation methodology.

- Sydney bus patronage is very difficult to estimate, as figures are not routinely published for private operators. I’ve used a BITRE time series for Greater Sydney bus patronage (related to this paper).

- The Sydney ferries figures include private operators (maybe 1-2 million per year), but I have had to estimate figures post 2009-10.

- Sydney Metro light rail don’t generally publish their patronage figures to great precision. The 2008-09 figure I have is 7 million (rounded to the nearest million).

- I have calculated the population of “Sydney+surrounds” as a combination of SA3 areas covering metropolitan Sydney, Newcastle, the Hunter Valley and Illawarra region. Here’s a map. Unfortunately it’s not a perfect match for the footprint of CityRail and “outer metropolitan” bus services, but I think reasonably close, particularly for trend analysis purposes.

- South East Queensland includes Greater Brisbane Statistical Area plus the SA4 areas of Sunshine Coast and Gold Coast.

- For other cities I have used population figures for Greater Perth (which includes Mandurah), Greater Adelaide and the Melbourne Statistical Division (estimated for 2011-12 based on an SA2 mapping, as towns within the “Greater Melbourne” Statistical Area that are not in the old Melbourne Statistical Division are not counted in official metropolitan bus and train patronage figures).

- For all financial year population figures I have averaged the June 30 estimates at either end of each financial year.

- I have not included:

- Hobart ferries (with limited commuter services)

- Queanbeyan buses (which connect Canberra with the satellite town of Queanbeyan, just over the border in NSW)

- Metropolitan V/Line services in Melbourne: diesel train services currently operate to Melton which is in the Melbourne Statistical Division and has bus patronage that is counted as “metropolitan”. In previous years, V/line diesel trains also serviced the metropolitan area between St Albans and Sunbury and between Broadmeadows and Craigieburn (until these sections were electrified). I understand the metropolitan patronage on these services is in the order of a few million boardings per year, which is less than 1% of total Melbourne public transport patronage.

- School holidays typically impact on public transport patronage (particularly suburban buses), and not all financial years contain the same number of (high patronage) school days as school holidays often straddle the June/July break of month. Different states have holidays in different weeks. This means that the individual growth figure for one year in one city might be impacted by up to 1-2% away from the underlying trend. However, this should wash out over several years for index values.

- Compiling patronage figures is a very messy business. I’ve done the best I can, but I cannot guarantee that there are no omissions or calculation errors.

Data sources:

- Data compiled by the “Federal Department of Transport” and the West Australian newspaper (credit to Andrew Probyn).

- Victorian Department of Transport

- Victorian Budget Papers

- Metlink (Vic), now absorbed by PTV

- PTAWA annual reports and TransPerth statistics

- DTEI and DPTI (SA) annual reports, media reports and personal communications

- NSW Bureau of Transport Statistics

- Metro Tasmania Annual Report

- TAMS annual reports (ACT)

- BITRE

- Translink (QLD)

- Ian Wallis and Associates (NZ)

- New Zealand Ministry of Transport, Transport Monitoring Indicator Framework

Posted by chrisloader

Posted by chrisloader