[updated March 2016 to add Canadian and New Zealand cities]

Just how much denser are European cities compared to Australian cities? What about Canadian and New Zealand cities? And does Australian style suburbia exist in European cities?

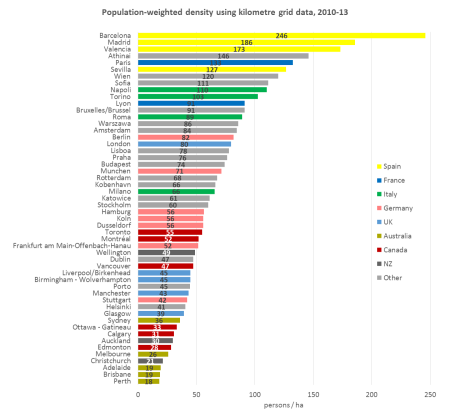

This post calculates the population-weighted density of 53 Australian, European, and Canadian cities with a population over 1 million, plus the three largest New Zealand cities (only Auckland is over 1 million population). It also shows a breakdown of the densities at which these cities’ residents live, and includes a set of density maps with identical scale and density shading.

Why Population Weighted Density?

As discussed in previous posts, population-weighted density attempts to measure the density at which the average city resident lives. Rather than divide the total population of a city by the entire city area (which usually includes large amounts of sparsely populated land), population weighted density is a weighted average of population density of all the parcels that make up the city. As I’ve shown previously, the size of the parcels used makes a big difference in the calculation of population-weighted density, which makes comparing cities difficult internationally.

To overcome the issue of different parcel sizes, I’ve used kilometre grid population data that is now available for both Europe and Australia. I’ve also generated my own kilometre population grids for Canadian and New Zealand cities by proportionally summing populations of the smallest census parcels available.

Some measures of density exclude all non-residential land, but the square kilometre grid approach means that partially populated grid parcels are counted, and many of these parcels will include non-residential land, and possibly even large amounts of water. It’s not perfect, particularly for cities with small footprints. For example, here is a density map around Sydney harbour (where light green is lower density, dark green is medium density and red is higher density):

You can see that many of the grid cells that include significant amounts of water show a lower density, when it fact the population of those cells are contained within the non-water parts of the grid cell. The more watery cells, the lower the calculated density. This is could count against a city like Sydney with a large harbour.

Defining cities

The second challenge with these calculations is a definition of the city limits. For Australia I’ve used Urban Centre boundaries, which attempt to include contiguous urbanised areas (read the full definition). For Europe I’ve used 2011 Morphological Urban Areas, which have fairly similar rules for boundaries. For Canada I’ve used Population Centre, and for New Zealand I’ve used Urban Areas.

These methodologies tend to exclude satellite towns of cities (less so in New Zealand and Canada). While these boundaries are not determined in the exactly the same way, one good thing about population-weighted density is that parcels of land that have very little population don’t have much impact on the overall result (because their low population has little weighting).

For each city, I’ve included every grid cell where the centroid of that cell is within the defined boundaries of the city. Yes that’s slightly arbitrary and not ideal for cities with dense cores on coastlines, but at least I’ve been consistent. It also means some of the cells around the boundary are excluded from the calculation, which to some extent offsets the coastline issues. It also means the values for Australian cities are slightly different to a previous post.

All source data is dated 2011, except for France which is 2010, and New Zealand which is 2013.

Comparing population-weighted density of Australian, European, Canadian and New Zealand cities

You can see the five Australian cities are all at the bottom, most UK cities are in the bottom third, and the four large Spanish cities are within the top seven.

Sydney is not far below Glasgow and Helsinki. Adelaide, Perth and Brisbane are nothing like the European cities when it comes to (average) population-weighted density.

Three Canadian cities (Vancouver, Toronto and Montreal) are mid-range, while the other three are more comparable with Australia. Of the New Zealand cities, Auckland is surprisingly more dense than Melbourne. Wellington is more dense that Vancouver (both topographically constrained cities).

But these figures are only averages, which makes we wonder…

How much diversity is there in urban density?

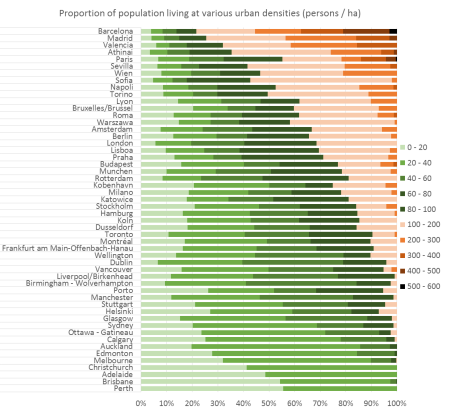

The following chart shows the proportion of each city’s population that lives at various urban density ranges:

Because of the massive variations in density, I had to break the scale interval sizes at 100 persons per hectare, and even then, the low density Australian cities are almost entirely composed of the bottom two intervals. You can see a lot of density diversity across European cities, and very little in Australian cities, except perhaps for Sydney.

You can also see that only 10% of Barcelona has an urban density similar to Perth or Adelaide. Which makes me wonder…

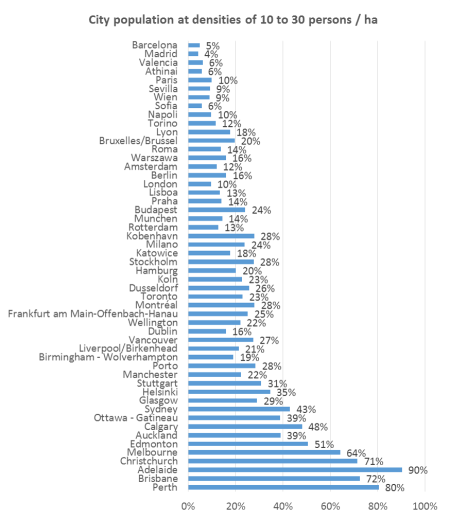

Do many people in European cities live at typical Australian suburban densities?

Do many Europeans living in cities live in detached dwellings with backyards, as is so common in Australian cities?

To try to answer this question, I’ve calculated the percentage of the population of each city that lives at between 10 and 30 people per hectare, which is a generous interpretation of typical Australian “suburbia”.

It’s a minority of the population in all European cities (and even for Sydney). But it does exist. Here are examples of Australian-style suburbia in outer Hamburg, Berlin, London, Milan, and even Barcelona (though I hate to think what some of the property prices might be!)

How different is population-weighted density from regular density?

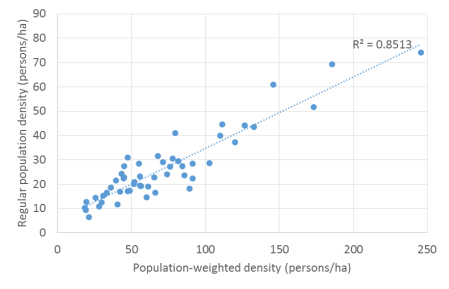

Now that I’ve got a large sample of cities, I can compare regular density with population weighted densities (PWD):

The correlation is relatively high, but there are plenty of outliers, and rankings are very different. Rome has a regular density of 18, but a PWD of 89, while London has a regular density of 41 and PWD of 80. Dublin’s regular density of 31 is relatively close to its PWD of 47.

Wellington’s regular density is 17, but its PWD is 49 (though the New Zealand cities regular density values are impacted by larger inclusions of non-urbanised land within definitions of Urban Areas).

So what does the density of these cities look like on a map?

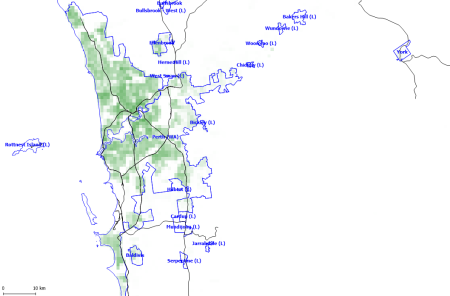

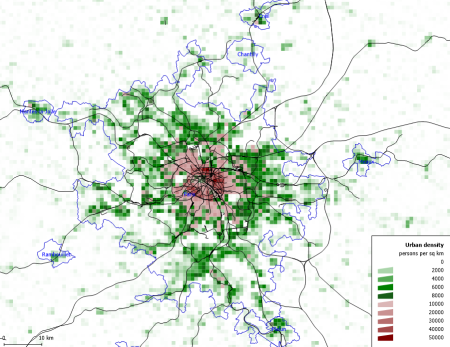

The following maps are all at the same scale both geographically and for density shading. The blue outlines are urban area boundaries, and the black lines represent rail lines (passenger or otherwise, and including some tramways). The density values are in persons per square kilometre (1000 persons per square kilometre = 10 persons per hectare). (Apologies for not having coastlines and for some of the blue labels being difficult to read).

Here’s Barcelona (and several neighbouring towns), Europe’s densest large city, hemmed in by hills and a coastline:

At the other extreme, here is Perth, a sea of low density and the only city that doesn’t fit on one tile at the same scale as the other cities (Mandurah is cut off in the south):

Here is Paris, where you can see the small high density inner core matches the high density Metro railway area:

Similarly the dense inner core of London correlates with the inner area covered by a mesh of radial and orbital railways, with relatively lower density outer London more dominated by radial railways:

There are many more interesting patterns in other cities.

What does this mean for transport?

Few people would disagree that higher population densities increase the viability of high frequency public transport services, and enable higher non-car mode shares – all other things being equal. But many (notably including the late Paul Mees) would argue that “density is not destiny” – and that careful design of public and active transport systems is critical to transport outcomes.

Zurich is a city often lauded for the high quality of its public transport system, and its population weighted density is 51 persons/ha (calculated on the kilometre grid data for a population of 768,000 people) – which is quite low relative to larger European cities.

In a future post I’ll look at the relationship between population-weighted density and transport mode shares in European cities.

All the density maps

Finally, here is a gallery of grid density maps of all the cities for your perusing pleasure (plus Zurich, plus many smaller neighbouring cities that fit onto the maps). All maps have the same scale and density shading colours.

Please note that the New Zealand and Canada maps do not include all nearby urbanised areas. Apologies that the formats are not all identical.

- Adelaide

- Amsterdam Rotterdam

- Athens

- Auckland

- Barcelona

- Berlin

- Birmingham

- Brisbane

- Brussels

- Budapest

- Calgary

- Christchurch

- Cologne Essen Dusseldorf

- Copenhagen

- Dublin

- Edmonton

- Frankfurt

- Glasgow

- Hamburg

- Helsinki

- Katowice

- Lisbon

- Liverpool-Manchester

- London

- Lyon

- Madrid

- Melbourne

- Milan

- Montreal

- Munich

- Naples

- Ottawa

- Paris

- Perth

- Porto

- Prague

- Rome

- Seville

- Sofia

- Stuttgart

- Stockholm

- Sydney

- Toronto

- Turin

- Valencia

- Vancouver

- Vienna

- Warsaw

- Wellington

- Zurich

Posted by chrisloader

Posted by chrisloader