Please refer to a fully revised second edition of this post – published in April 2019.

[Updated April 2017 with 2015-16 population estimates. First published November 2013]

While Australian cities have been growing outwards with new suburbia, they have also been getting denser in established areas, and the new areas on the fringe are often more dense than growth areas used to be (see last post). So what’s the net effect – are Australian cities getting more or less dense?

This post also explores measures of population-weighted density for Australian cities large and small over time. It also tries to resolve some of the issues in the calculation methodology by using square kilometre geometry, looks at longer term trends for Australian cities, and then compares multiple density measures for Melbourne over time.

Measuring density

Under the traditional measure of density, you’d simply divide the population of a city by the metropolitan area’s area (in hectares). As the boundary of the metropolitan areas seldom change, the average density would simply increase in line with population with this measure. But that density value would also be way below the density at which the average resident lives because of the inclusion of vast swaths of unpopulated land within “metropolitan areas”, and so be not very meaningful.

Enter population-weighted density (which I’ve looked at previously here and here). Population-weighted density takes a weighted average of the density of all parcels of land that make up a city, with each parcel weighted by its population. One way to think about it is the residential density in which the “average resident” lives.

So the large low-density parcels of rural land outside the urbanised area but inside the “metropolitan area” count very little in the weighted average because of their small population relative to the urbanised areas. This means population-weighted density goes a long way to overcoming having to worry about the boundaries of the “urban area” of a city. Indeed, in a previous post I found that removing low density parcels of land had very little impact on calculations of population-weighted density for Australian cities. However, the size of the parcels of land used in a population-weighted density calculation will have an impact, as we will see shortly.

Calculations of population-weighted density can answer the question about whether the “average density” of a city has been increasing or decreasing. But as we will see below, using geographic regions put together by statisticians based on historical boundaries is not always a fair way to compare different cities.

Population-weighted density of Australian cities over time

Firstly, here is a look at population-weighted density of the five largest Australian cities (as defined by ABS Significant Urban Areas), measured at SA2 level (the smallest geography for which there exists a good consistent set of time-series estimates). SA2s roughly equate to suburbs.

According to this data, most cities bottomed out in density in the mid 1990s. Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane have shown the fastest rates of densification in the last three years.

What about smaller Australian cities? (120,000+ residents in 2014):

Darwin comes out as the third most dense city in Australia on this measure, with Brisbane rising quickly in recent years into fourth place. Most cities have shown densification in recent times, with the main exception being Townsville. On an SA2 level, population weighted density in Perth hardly rose at all in 2015-16 (a year when 92% of population growth was in the outer suburbs)

However, we need to sanity test these values. Old-school suburban areas of Australian cities typically have a density of around 15 persons per hectare, so the values for Geelong, Newcastle, Darwin, Townsville, and Hobart all seem a bit too low for anyone who has visited them. I’d suggest the results may well be an artefact of the arbitrary geographic boundaries used – and this effect would be greater for smaller cities because they would have more SA2s on the interface between urban and rural areas (indeed all of those cities are less than 210,000 in population).

For reference, here are the June 2014 populations of all the above cities:

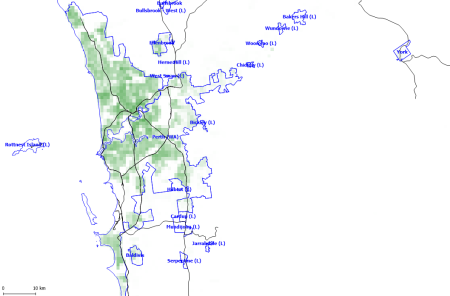

The following map shows Hobart, with meshblock boundaries in black (very small blocks indicate urban areas), SA2s in pink, and the Significant Urban Area (SUA) boundary in green. You can see that many of the SA2s within the Hobart SUA have pockets of dense urban settlement, together with large areas that are non-urban – ie SA2s on the urban/rural interface. The density of these pockets will be washed out because of the size of the SA2s.

Reducing the impact of arbitrary geographic boundaries

As we saw above, the population-weighted density results for smaller cities were very low, and probably not reflective of the actual typical densities, which might be caused by arbitrary geographic boundaries.

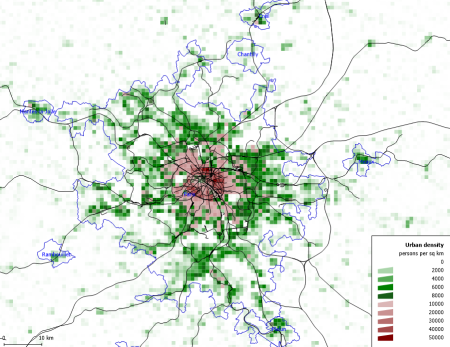

Thankfully ABS have followed Europe and released of a square kilometre grid density for Australia which ensures that geographic zones are all the same size. While it is still somewhat arbitrary where exactly this grid falls on any given city, it is arguably less arbitrary than geographic zones that follow traditional notions of area boundaries.

Using that data, I’ve been able to calculate population weighted density for the larger cities of Australia. The following chart shows those values compared to values calculated on SA2 geography:

You’ll see that the five smaller cities (Newcastle, Hobart, Geelong, Townsville and Cairns) that had very low results at SA2 level get more realistic values on the kilometre grid.

You’ll notice that most cities (except big Melbourne and Sydney) are in the 15 to 18 persons per hectare range, which is around typical Australian suburban density.

While the Hobart figure is higher using the grid geography, it’s still quite low (indeed the lowest of all the cities). You’ll notice on the map above that urban Hobart hugs the quite wide and windy Derwent River, and as such a larger portion of Hobart’s grid squares are likely to contain both urban and water portions – with the water portions washing out the density (pardon the pun!). While most other cities also have some coastline, much more of Hobart’s urban settlement is near to a coastline.

But stepping back, every city has urban/rural and/or urban/water boundaries and the boundary has to be drawn somewhere. So smaller cities are always going to have a higher proportion of their land parcels being on the interface – and this is even more the case if you are using larger parcel sizes. There is also the issue of what “satellite” urban settlements to include within a city which ultimately becomes arbitrary at some point. Perhaps there is some way of adjusting for this interface effect depending on the size of the city, but I’m not going to attempt to resolve it in this post.

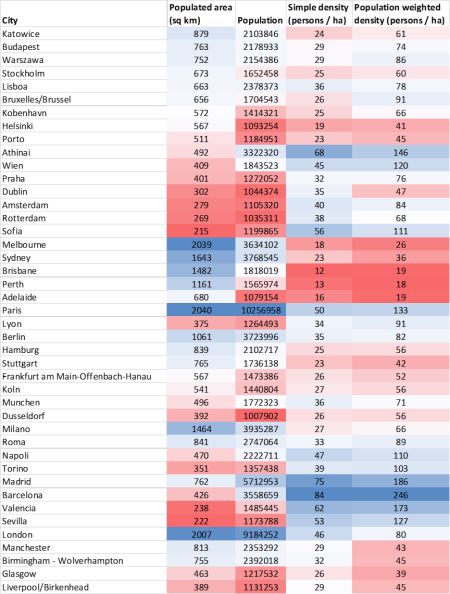

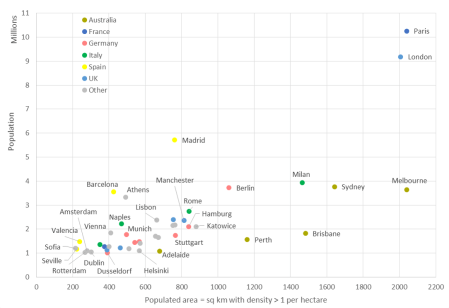

International comparisons of population-weighted density

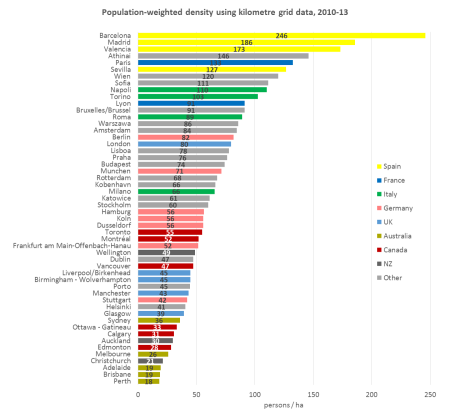

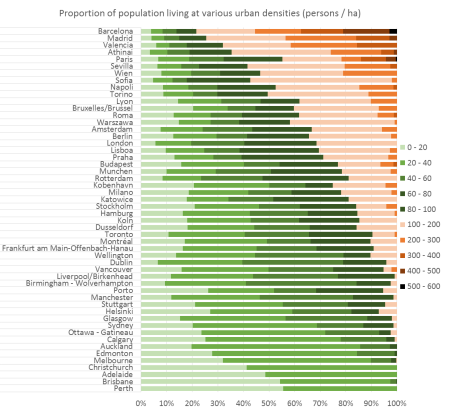

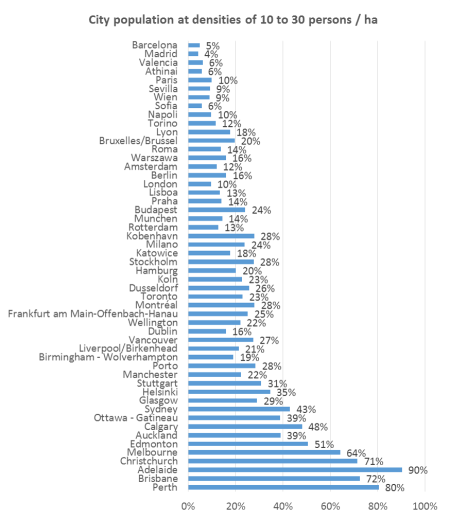

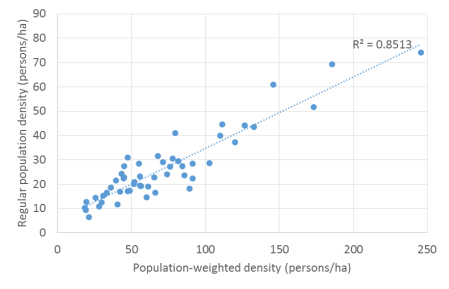

See another post for some international comparisons using square km grids.

Changes in density of larger Australian cities since 1981

We can also calculate population-weighted density back to 1981 using the larger SA3 geography. An SA3 is roughly similar to a local government area (in Melbourne at least), so getting quite large and including more non-urban land. Also, as Significant Urban Areas are defined only at the SA2 level, I need to resort to Greater Capital City Statistical Areas for the next chart:

This shows that most cities were getting less dense in the 1980s (Melbourne quite dramatically), with the notable exception of Perth. I expect these trends could be related to changes in housing/planning policy over time. This calculation has Adelaide ahead of the other smaller cities – which is different ordering to the SA2 calculations above.

On the SA3 level, Perth declined in population-weighted density in 2015-16.

When measured at SA2 level, the four smaller cities had almost the same density in 2011, but at SA3 level, there is more separating them. My guess is that the arbitrary nature of geographic boundaries is having an impact here. Also, the share of SA3s in a city that are on the urban/rural interface is likely to be higher, which again will have more impact for smaller cities. Indeed the trend for the ACT at SA3 level is very different to Canberra at SA2 level.

Melbourne’s population-weighted density over time

I’ve taken a more detailed look at my home city Melbourne, using all available ABS population figures for the geographic units ranging from mesh blocks to SA3s inside “Greater Melbourne” (as defined in 2011) or inside the Melbourne Significant Urban Area (SUA, where marked), to produce the following chart:

Note: I’ve calculated population-weighted density at the SA2 level for both the Greater Capital City Statistical Area (ie “Greater Melbourne”, which includes Bacchus Marsh, Gisborne and Wallan) and the Melbourne Significant Urban Area (slightly smaller), which yield slightly different values.

All of the time series data suggests 1994 was the turning point in Melbourne where the population-weighted density started increasing (not that 1994 was a particularly momentous year – the population-weighted density increased by a whopping 0.0559 persons per hectare in the year to June 1995 (measured at SA2 level for Greater Melbourne)).

You’ll also note that the density values are very different when measured on different geographic units. That’s because larger units include more of a mix of residential and non-residential land. The highest density values are calculated using mesh blocks (MB), which often separate out even small pockets of non-residential land (eg local parks). Indeed 25% of mesh blocks in Australia had zero population, while only 2% of SA1s had zero population (at the 2011 census). At the other end of the scale, SA3s are roughly the size of local councils and include parklands, employment land, rural land, airports, freeways, etc which dilutes their average density.

In the case of SA2 and SA3 units, the same geographic areas have been used in the data for all years. On the other hand, Census Collector Districts (CD) often changed between each five-yearly census, but I am assuming the guidelines for their creation would not have changed significantly.

Now why is a transport blog so interested in density again? There is a suggested relationship between (potential) public transport efficiency and urban density – ie there will be more potential customers per route kilometre in a denser area. In reality longer distance public transport services are going to be mostly serving the larger urban blob that is a city – and these vehicles need to pass large parklands, industrial areas, water bodies, etc to connect urban origins and destinations. The relevant density measure to consider for such services might best be based on larger geographic areas – eg SA3. Buses are more likely to be serving only urbanised areas, and so are perhaps more dependent on residential density – best calculated on a smaller geographic scale, probably km grid (somewhere between SA1 and SA2).

You may also like

Posted by chrisloader

Posted by chrisloader