Relatively dense suburban employment clusters can deliver more knowledge-based jobs closer to people living in the outer suburbs. Sydney has many such clusters, and Melbourne is now aiming to develop “National Employment and Innovation Clusters” as part of the city’s land use strategy, Plan Melbourne.

So what can we learn about existing employment clusters in Australian cities, particularly in regards to journeys to work? Can relatively dense suburban employment clusters contribute to more sustainable transport outcomes? Do such clusters have lower private transport mode shares than other parts of cities? How are mode shares changing for these clusters? How far do people travel to work in these clusters? Is there a relationship between job density, parking prices, and mode shares? How well served are these clusters by public transport? How do these clusters compare between cities?

This post investigates 46 existing clusters in Australia’s six largest cities. This is a longer post (there is a summary at the end), but I hope you find at least half as interesting as I do.

What’s a dense suburban employment cluster?

That’s always going to be an arbitrary matter. For my analysis, I’ve created clusters based on destination zones that had at least 40 employees per hectare in 2011 or 2016, were more than 4km from the city’s main CBD, and where collectively at least around 6,000 employees travelled on census day in 2016.

Unfortunately I can only work with the destination zone boundaries which may or may not tightly wrap around dense employment areas. Also, in order to ensure reasonable comparisons between census years, I’ve had to add in some otherwise non-qualifying zones to keep the footprints fairly similar. To mitigate potential issues with low density zones being included, I’ve used weighted employment density for each cluster in my analysis. But still, please don’t get too excited by differences in weighted job density as it’s far from a perfect representation of reality.

In particular, the following clusters include destination zones comprising both dense employment and non-employment land and so will potentially have understated weighted job density:

- Nedlands

- Fremantle

- Bedford Park

- Tooronga

- Camberwell Junction

- Hawthorn

- Belconnen

- Campbelltown

- Hurstville

- Kogarah

- Randwick

- North Ryde (quite significant – actual density is probably double)

- Macquarie Park (a destination zone for the university includes large green areas)

- Rhodes (significant residential area)

- Parramatta (includes parkland)

- Penrith (residential areas)

- Bella Vista – Norwest – Castle Hill (includes a golf course)

Some of these clusters are a little long and thin and so are literally stretching things a little (eg Bella Vista – Norwest – Castle Hill, and Alexandria – Mascot), but it’s hard to cleanly break up these areas.

I think my criteria is a fairly low threshold for suburban employment clusters, but raising the criteria too much would knock out a lot of clusters. I should note that some potential clusters might be excluded simply because they did not contain small destination zones concentrated on more dense areas.

Belmont in Perth was the lowest density cluster to qualify (weighted jobs density of 42 jobs / ha). Here’s what it looks like (in 3D Google Maps in 2018):

Chatswood in Sydney was the highest density cluster – with a weighted job density of 433 jobs / ha. Here’s what it looks like (in 3D Apple Maps in 2018):

Apologies if your favourite cluster didn’t make the criteria, or you don’t like my boundaries. You can look up the 2016 boundaries for each cluster here, or view them all through Google maps.

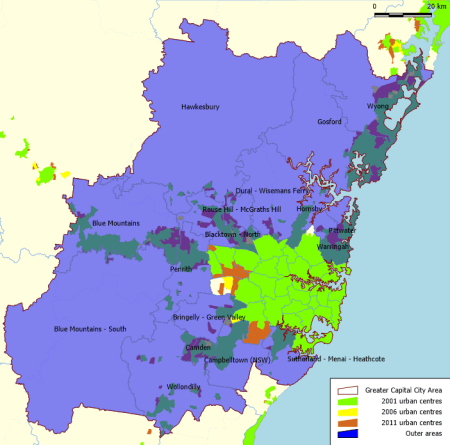

Where are these clusters?

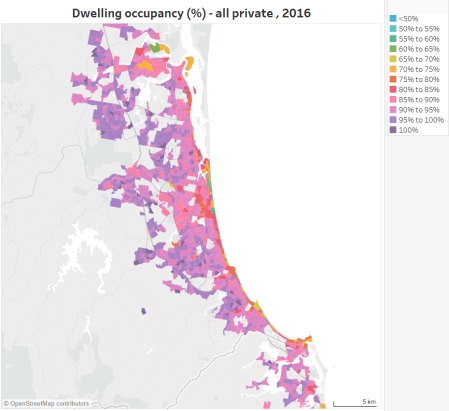

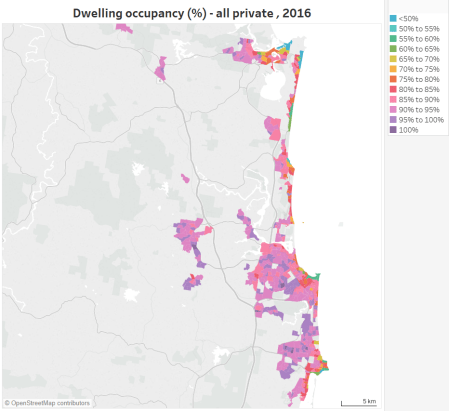

On the following maps I’ve scaled the clusters by employment size and used pie charts to show the modal split for journeys to work in 2016. All pie charts are to the same scale across the maps (the size of the pie charts is proportional to the number of journeys to the cluster in 2016).

Note that North Sydney is excluded because it is within 4 km of the CBD.

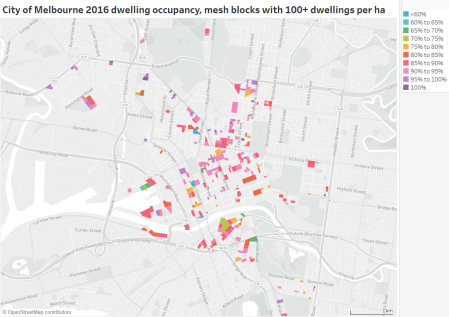

All of Melbourne’s clusters are east of the CBD, with Clayton the largest. Places just missing out on the cluster criteria include parts of the Tullamarine industrial area (5271 jobs at 55 jobs/ha), Doncaster (around 5000 jobs at 40+ jobs/ha), Chadstone Shopping Centre (5375 jobs at 105 jobs/ha), and La Trobe (around 7700 jobs but low density – and even if there was a destination zone tightly surrounding the university campus I suspect it would still not qualify on density ground).

Only three suburban clusters qualified in Brisbane.

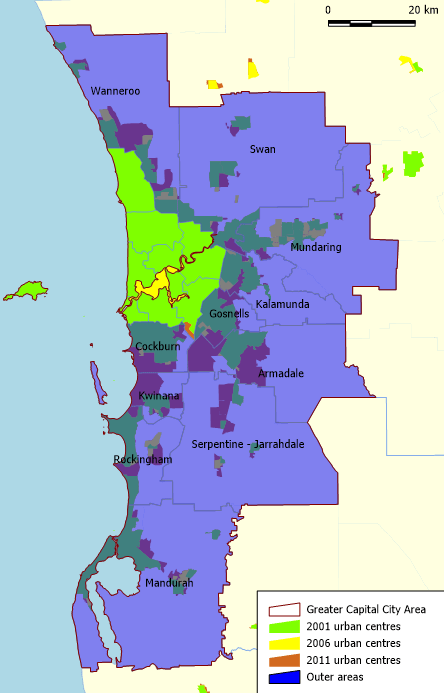

Note: the Nedlands and Murdoch clusters are essentially the hospital precincts only and do not include the adjacent university campuses.

Adelaide only has one suburban cluster that qualifies – Bedford Park – which includes the Flinders University campus and Flinders Medical Centre.

The Canberra clusters cover the three largest town centres, each containing at least one major federal government department head office.

What proportion of jobs are in these dense suburban employment clusters?

The following chart shows that Sydney and Canberra have been most successful at locating jobs in suburban employment clusters (well, clusters that meet my arbitrary criteria anyway!):

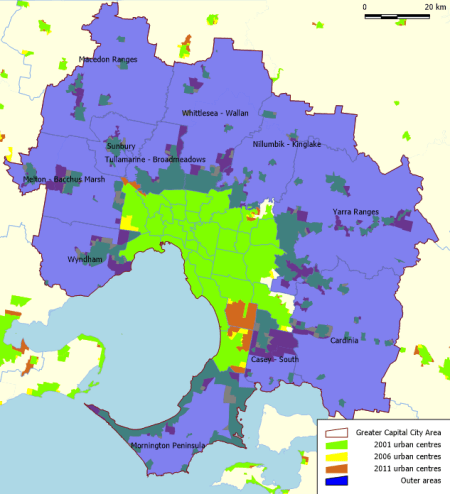

The proportion of jobs not in the inner 4km or a suburban employment cluster increased between 2011 and 2016 in all cities except Sydney (although the shift was very small in Melbourne).

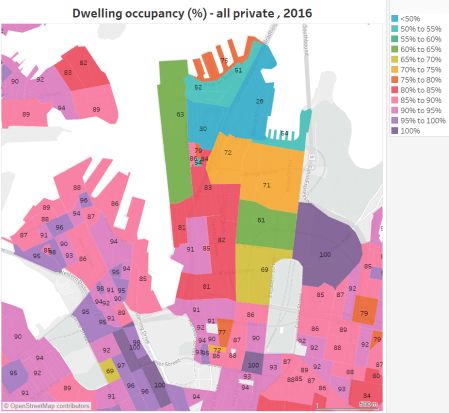

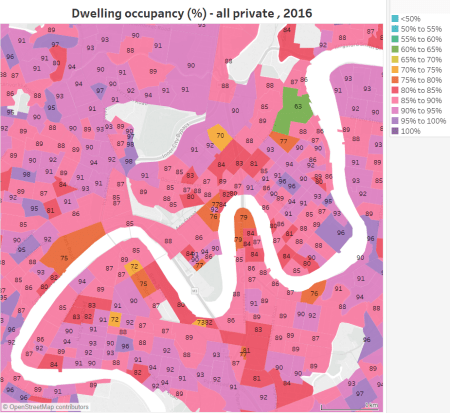

Here’s a summary of private transport mode shares for the clusters, versus the inner city versus everywhere else:

Inner city mode shares vary considerably between cities, in order of population size. Total job cluster private mode shares are only 4-7% lower than elsewhere in most cities, except for Sydney where they are 17% lower.

Sydney’s clusters combined also have a significantly lower private mode share of 68% – compared to 84-89% in other cities.

How do the clusters compare?

Here is a chart showing their size, distance from CBD, and private transport mode share for journeys to work in 2016:

Next is a chart that looks at weighted job density, size, and private mode share for 2016. Note I’ve used a log scale on the X axis.

(Unfortunately the smaller Kogarah dot is entirely obscured by the larger Alexandria – Mascot dot – sorry that’s just how the data falls)

There is certainly a strong relationship between weighted job density and private mode shares (in fact this is the strongest of all relationships I’ve tested).

Sydney has many more clusters than the other cities (even Melbourne which has a similar population), it has much larger clusters, it has more dense clusters, and accounts for most of the clusters in the bottom-right of the chart.

And there’s just nothing like Parramatta in any other city. It’s large (~41,000 jobs in 2016), has relatively low private transport mode share (51%), is about 20 km from the Sydney CBD, and has a high jobs density.

Melbourne’s Clayton has about three-quarters the jobs of Parramatta, is around the same distance from its CBD, but is much less dense and has 90% private mode share for journeys to work.

Curiously Sydney’s Macquarie Park – which on my boundaries has about the same number of jobs as Parramatta – is closer to the Sydney CBD and has a much higher private transport mode share and a lower job density. However it’s rail service is relatively new, opening in 2009.

Perth’s Joondalup and Murdoch are relatively young transit oriented developments with relatively new train stations (opening 1992 and 2007 respectively), however they also have very high private transport mode shares, which I think highlights the challenge of creating suburban transit-adjacent employments clusters surrounded by low density suburbia.

Also, many of Sydney’s suburban clusters have a lower private mode share than that of the overall city (67.6%). That’s only true of Hawthorn and Camberwell Junction in Melbourne, Fremantle in Perth, and Woden and Belconnen in Canberra.

Some outliers to the top-right of the second chart include Heidelberg (in Melbourne), Liverpool (in Sydney), and Nedlands (in Perth). The Heidelberg and Nedlands clusters are relatively small and are dominated by hospitals, while 37% of jobs in Liverpool are in “health care and social assistance”. Hospitals employ many shift workers, who need to travel at times when public transport is less frequent or non-existent which probably explains their relatively high private transport mode shares. Heidelberg is located on a train line, and is also served by several relatively frequent bus routes, including one “SmartBus” route, but still has a very high private transport mode share of 85%.

Outliers to the bottom-left of the second chart include Randwick, Burwood, and Marrickville (all in Sydney). While these are less dense clusters, I suspect their relatively low private transport mode shares are because they are relatively inner city locations well served by public transport.

As an aside, if you were wondering about the relationship between job density and private mode shares for inner city areas, I think this chart is fairly convincing:

Of course this is not to say if you simply increase job density you’ll magically grow public transport patronage – there has to be capacity and service quality, and you probably won’t get the density increase without better public transport anyway.

How well connected are these job clusters to public transport?

Arguably the presence of rapid public transport is critical to enabling high public transport mode shares, as only rapid services can be time competitive with private transport. By “rapid” I consider services that are mostly separated from traffic, have long stop spacing, and therefore faster average speeds. For Australian cities this is mostly trains, but also some busways and light rail lines (but none of the clusters are served by what I would call “rapid” light rail). Of course there is a spectrum of speeds, including many partly separated tram and bus routes, and limited stops or express bus routes, but these often aren’t time competitive with private cars (they can however compete with parking costs).

I have classified each cluster by their access to rapid transit stations, with trains trumping busways (note Parramatta, Blacktown, Westmead, and Liverpool have both), and some clusters sub-classified as “edge” where only some edge areas of the cluster are within walking distance of a rapid transit station (although that’s not clear cut, eg Murdoch). Here are the public transport mode shares, split by whether journeys involved trains or not:

It’s probably of little surprise that all of the high public transport mode share centres are on train lines (except Randwick), and that most public transport journeys to these clusters involve trains. However the presence of a train station certainly does not guarantee higher public transport mode share.

Only four clusters have some degree of busway access (Chermside and Randwick are not actually on a busway but have a major line to them that uses a busway). Only Upper Mount Gravatt has a central busway stations, and it has the third highest non-train (read: bus) access share of 12%.

Randwick is an interesting exception – the University of New South Wales campus in this cluster is connected to Central (train) Station by high frequency express bus services which seem to win considerable mode share. A light rail connection is being constructed between Randwick and the Sydney CBD.

Non-rail (essentially bus) public transport mode shares are also relatively high in Bondi Junction (15%), Parramatta (11%), Belconnen (10%), Brookvale (10%), Woden (10%), Fremantle (9%), Macquarie Park (9%). These are all relatively strong bus nodes in their city’s networks.

Clayton and Nedlands are not on rapid transit lines, but both have high frequency bus services to nearby train stations which results in slightly higher train mode shares (4% and 5%). For Clayton, only the Monash University campus is connected by a high frequency express bus and it had a 17% public transport mode share, whereas the rest of the cluster had public transport mode shares varying between 3 and 7%.

The Bedford Park cluster is frustratingly just beyond reasonable walking distance of Tonsley Railway Station (12 minutes walk to the hospitals and almost half an hour’s walk to the university campus) – so only about 10 people got to work in the cluster by train in 2016. However that’s going to change with an extension of the train line to the Flinders Medical Centre.

The train-centred clusters with low public transport mode shares are mostly not in Sydney, and/or towards outer extremities of the train network (except Box Hill and Heidelberg in Melbourne). So what is it about Sydney’s trains that makes such a difference?

Sydney’s train network is distinctly different to all other Australian cities in that there are many more points where lines intersect (outside the central city), creating many “loops” on the network (for want of a better expression). In all other cities, lines only generally intersect in the central city and where radial lines split into branches, and cross city trips by public transport generally only possible by buses (in mixed traffic). In Sydney lines do branch out then but then often bend around to intersect other neighbouring lines. This provides significantly more connectivity between stations. For example, you can get to Parramatta from most lines directly or with a single transfer somewhere outside central Sydney. Indeed, Sydney is the only city with a regular non-radial train service (T5 Leppington – Richmond, although it only runs every half-hour).

I’ve roughly overlaid Sydney’s dense suburban job clusters (in red) on its rail network map, and then marked the train mode shares:

While some clusters can only be accessed by a radial train line (or are off-rail), many are at intersection points, and most can be accessed by multiple paths along the network. The 29%+ train mode shares for Chatswood, Parramatta, St Leonards, Burwood, and Rhodes might be partly explained by these being highly accessible on the train network.

Here are Melbourne’s dense suburban employment clusters and train mode shares overlaid on Victoria’s rail network map:

The clusters connected to more train lines (Hawthorn and Camberwell) have higher train mode shares, although they are also closer to the city.

The Spatial Network Analysis for Multimodal Urban Transport Systems (SNAMUTS) methodology (led by Professor Carey Curtis and Dr Jan Scheurer) uses graph-based analysis of public transport networks to develop several indicators of network performance. One indicator that measures network accessibility is closeness centrality, which looks and speed and frequency of services to connect to other nodes in the network (it actually uses inter-peak frequencies and speeds, but they probably correlate fairly well with services in peak periods). A lower score indicates better accessibility.

I’ve extracted the closeness centrality scores for public transport nodes in each employment clusters (from the nearest available data to 2016 at the time of writing, some as old as 2011 so not perfect) and compared this with private transport mode shares to these clusters:

Some clusters were not really centred on a public transport node in the SNAMUTS analysis (eg Osborne Park in Perth, Clayton in Melbourne) and hence are not included in this analysis. These clusters have very high private transport mode shares, and would likely be towards the top right of the chart.

There’s clearly a relationship between the closeness centrality and private mode shares, with low private more shares only occurring where there is high accessibility by public transport. But it’s not super-strong, so there are other factors at play.

Some of the outliers in the bottom right of the distribution include Upper Mount Gravatt (based on a large shopping centre but also on a busway), Murdoch (dominated by hospitals a moderate walk from the station), Nedlands (also dominated by hospitals), Chermside (a combination of hospital and large shopping centre, with the bus interchange remote from the hospital), and Bedford Park (where 63% of jobs are in health) . Again, the pattern of higher private transport mode shares to hospitals is evident.

So do you need strong public transport access to support higher job densities? Here’s the relationship between closeness centrality and weighted job density:

There are no clusters with poor public transport access and high job density, which is not surprising. But this does suggest it could be difficult to significantly increase job densities in clusters currently in the top left of this chart without significantly improving public transport access.

Interestingly, Box Hill in Melbourne does have a similar closeness centrality score to Parramatta and Chatswood in Sydney, suggesting it might be able to support significantly higher job density. However, it only has rapid (train) public transport from two directions. It might be more challenging to maintain bus and tram travel times from other directions if there is significant jobs growth.

Melbourne’s largest cluster – Clayton – is not on the chart because it is not centred on a public transport node. There is however a bus interchange on the southern edge of the cluster at Monash University, which has a relatively low closeness centrality score of 64. I suspect the main employment area would probably have a higher closeness centrality score if it were to be measured because it not connected to the train network by a high frequency express shuttle service and has fewer bus routes. That would place it in the top-left part of the above chart (2016 weighted job density being 63 jobs/ha).

Do higher density clusters have fewer car parks?

The higher density centres certainly tended to have lower private mode shares, but does that mean they don’t have much car parking?

Well I don’t know how many car parking spaces each centre had, but I do know how many people travelled to work by car only, and from that I can calculate a density of car-only journeys (and I’ve calculated a weighted average of the destination zones in each centre). That’s probably a reasonable proxy for car park density.

Here’s how it compares to jobs density (note: log scales on both axes):

There is a very strong correlation between the two – in general centres with higher job density also have higher car density. The strongest correlation I can find is for a quadratic curve that flattens out at higher job densities (as drawn, with R-squared = 0.77), which simply suggests you get lower private mode shares in higher density clusters (in general).

The clusters on the bottom side of the curve have lower car mode shares, and so have a lower car density. Many are inner city locations with better public transport access, but also many nearby residents.

Heidelberg (a hospital-based cluster in Melbourne), has the highest car density of all centres and a high job density, but isn’t a large centre.

Do walking mode shares increase when there are many nearby residents?

If there are many residents living within walking distance of a cluster, relative to the size of that cluster, then you might expect a higher walking mode share, as more employees of the cluster are likely to live nearby.

I’ve roughly summed the number of residents who travelled to work (anywhere) and lived within 1km of each cluster. I’ve then taken the ratio of those nearby working residents to the number of journeys into the cluster, and then compared that with walk-only mode shares for 2016:

Yes, there’s definitely a relationship (although not strong), and this may explain some of the outliers in the previous charts such as Randwick, Marrickville, St Leonards and Bondi Junction.

Is there a relationship between parking costs and mode shares?

It’s quite difficult to definitively answer this question because I don’t have parking prices for 2016, and many car commuters might not be paying retail prices (eg employer-provided free or subsidised parking).

I’ve done a quick survey using Parkopedia of parking prices for parking 8:30 am to 5:30 pm on Monday 2 July 2018, and picked the best price available in each cluster. Of course not everyone will be able park in the cheapest car park so it’s certainly not an ideal measure. An average price might be a slightly better measure but that would be some work to calculate.

But for what it worth, here is the relationship between July 2018 all day parking prices and 2016 private transport mode shares:

You might expect an inverse correlation between the two. Certainly clusters with very cheap or free parking had very high private transport mode shares, but other centres are scattered in the distribution.

Looking at outliers in the top right: I suspect Bedford Park (63% health workers), Heidelberg (hospital precinct), Tooronga (with one major employer being the Coles HQ), Chermside (including Prince Charles Hospital), and Rhodes will have significantly cheaper parking for employees (with visitors paying the prices listed on Parkopedia). Indeed, I could not find many parking prices listed for Rhodes, but there are clearly multi-storey parking garages near the office towers not on Parkopedia.

Looking at outliers in the bottom left: Relatively cheap $15 parking is available at multiple car parks in Bondi Junction. The $10 price in Chatswood was only available at one car park, with higher prices at others, so it is probably below the average price paid. Maybe traffic congestion is enough of a disincentive to drive to work in these centres?

For interest, here’s the relationship between weighted car density and parking prices:

The relationship is again not very strong – I suspect other factors are at play such as unlisted employer provided car parking, as discussed above.

So does job growth in suburban employment clusters lead to lower overall private transport mode shares?

Here is a chart showing the effective private mode share of net new trips in each job cluster, plus the inner 4 km of each city:

(Fremantle, Dandenong, Burwood, and Woden had a net decline in jobs between 2011 and 2016 and so have been excluded from this chart)

The chart shows that although many suburban jobs clusters had a low private mode share of net new trips, it was always higher than for the inner 4 km of that city.

Here’s a summary of net new trips for each city:

So every new 100 jobs in suburban employment clusters did generate many more private transport trips than new jobs in the inner city, particularly for Sydney (45 : 10), Melbourne (68 : 13), and Canberra (84: 18). But then new jobs in suburban employment clusters had significantly lower private transport mode shares than new jobs elsewhere in each city.

So arguably if you wanted to minimise new private transport journeys to work, you’d aim for a significant portion of your employment growth in the central city, and most of the rest in employment clusters (ideally clusters that have excellent access by rapid public transport). Of course you would also want to ensure your central city and employment clusters were accessible by high quality / rapid public transport links (not to forget active transport links for shorter distance commutes).

One argument for growing jobs in suburban employment clusters is that new public transport trips to suburban employment clusters will often be on less congested sections of the public transport network – particularly on train networks (some would even involve contra-peak travel relative to central city). On the other hand, new jobs in the central city have much higher public transport mode shares, but relatively expensive capacity upgrades may be required to facilitate the growth.

New active transport trips to the central city and employment clusters probably requires the least in terms of new infrastructure, and there are probably very few congested commuter cycleways in Australian cities at present.

Another argument for suburban employment clusters is to bring jobs closer to people living in the outer suburbs.

Are new private transport trips to suburban employment clusters much shorter than new private transport trips to the central city, and therefore perhaps not as bad from a congestion / emissions point of view?

Certainly many of these clusters will have congested roads in peak periods, but the distance question is worth investigating.

So how far do people travel to work in different employment clusters?

The 2016 census journey to work data now includes on-road commuting distances (thanks ABS!).

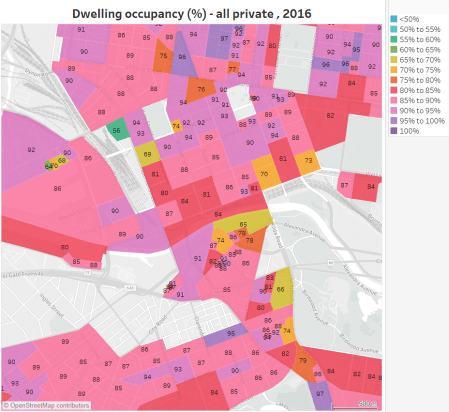

Of course for any jobs cluster there will be a range of people making shorter and longer distance trips and it is difficult to summarise the distribution in one statistic. Averages are not great because they are skewed by a small number of very long distance commutes. For the want of something better, I’ve calculated medians, and here are calculations for Sydney job clusters:

(I’ve added a “Sydney” jobs cluster which is the “Sydney – Haymarket – The Rocks” SA2 that covers the CBD area).

There’s a lot going on in this data:

- Median distances for private transport commutes to most employment clusters are longer than to the CBD (particularly the big clusters of Macquarie Park and Parramatta).

- The clusters of Brookvale, Bondi Junction, and Randwick near the east coast have lower medians for motorised modes, probably reflecting smaller catchments. Randwick and Brookvale also do not have rail access, which might explain their low median public transport commute distances.

- Public transport median commute distances were longer in the rail-based near-CBD clusters of Bondi Junction, Alexandria – Mascot, and St Leonards, but also in some further out rail-based clusters, including Parramatta, Westmead and Penrith.

- Penrith – the cluster furthest from the Sydney CBD – curiously had the longer public transport median commute distance, which probably reflects good access from longer distance rail services (but public transport mode share was only 14%).

- Active transport medians vary considerably, and this might be impacted by the mix of shorter walking and longer cycling trips. For example, North Ryde saw more cycling than walking trips, but also had only 1% active transport mode share.

Here’s the same for Melbourne (with a cluster created for the CBD):

Clayton, Dandenong, and Melbourne CBD median commute distances were very similar, whereas median commutes to other clusters were mostly shorter.

Here are results for clusters in the smaller cities:

In Perth, Joondalup had shorter median commuter distances, while Osborne Park and Murdoch (both near rapid train lines) had the longest median public transport journey distances (but not very high public transport mode shares: 7% and 15% respectively). Half of the suburban clusters had a longer median private transport distance than the CBD, and half were shorter.

In Brisbane, median private commute distances were shorter in Chermside, but similar to the city centre for other clusters.

Coming back to our question, only some suburban employment clusters have shorter median private transport commute distances. I expect the slightly shorter distances for those clusters would not cancel out the much higher private transport mode shares, and therefore new suburban cluster jobs would be generating more vehicle kms than new central city jobs.

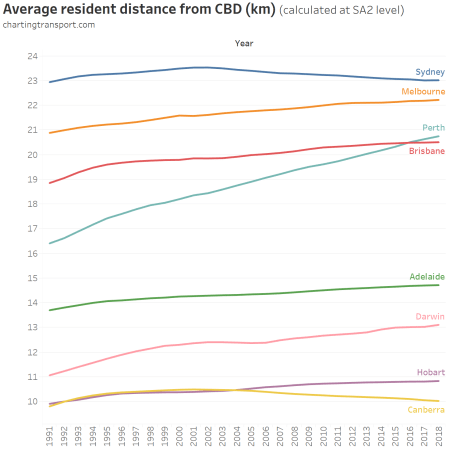

But perhaps what matters more is the distance travelled by new commuters. New trips from the growing urban fringe to a CBD would be very long in all cities. While ABS haven’t provided detailed journey distance data for 2011, some imperfect analysis of 2011 and 2016 straight line commuter distances between SA2s (sorry not good enough to present in detail) suggests average commuter distances are increasing by 1-2 kms across Sydney and 2-3 kms across Melbourne, and these increases are fairly consistent across the city (including the central city). This may reflect urban sprawl (stronger in Melbourne than Sydney), with new residents on the urban fringe a long way from most jobs.

So did private transport mode shares reduce in suburban employment clusters?

Yes, they did reduce in most clusters, but some saw an increase of up to 2%.

The cluster with the biggest shift away from private transport was Rhodes in Sydney (relatively small and only moderately dense), followed by Perth’s fastest growing hospital cluster of Murdoch.

But perhaps more relevant is how fast each cluster is growing and the mode share of new jobs:

If you want to reduce private transport travel growth, then you don’t want to see many clusters in the top right of this chart (growing fast with high dependency on private transport). Those centres could be experiencing increasing traffic congestion, and may start to hit growth limits unless they get significantly improved public transport access.

Of the cluster in the top-right:

- Bella Vista – Norwest – Castle Hill will soon have a rapid rail service with Sydney Metro.

- Murdoch’s high private transport mode share might reflect the fairly long walking distance between the station and hospitals (up to 10 minutes through open space with no tree canopy), but also hospital shift workers who may find private transport more convenient.

- Clayton might reflect most jobs being remote from the train line (although it is served by three SmartBus routes that have high frequency and some on-road priority). Note: my Monash cluster unfortunately does not include the Monash Medical Centre that is closer to Clayton Station and very job dense. The hospital precinct had its own destination zone in 2016 with 88% private transport mode share, but was washed out in a larger destination zone in 2011 which made it difficult to include in the cluster (for the record, that 2011 destination zone also had an 88% private transport mode share).

- Joondalup is a large but not particularly dense employment area, and I suspect many jobs are remote from the train/bus interchange, and some local bus frequencies are low.

Can you predict mode shares with a mathematical model?

I have put the data used above into a regression model trying to explain private transport mode shares in the clusters. I found that only weighted job density, walking catchment size, and distance from CBD were significant variables, but this might be for want of a better measure of the quality of public transport accessibility (SNAMUTS Closeness Centrality scores are not available for many centres).

I also tested the percentage of jobs in health care and social assistance (looking for a hospital effect), the surrounding population up to 10km (nearby population density), median travel distances, and the size of clusters, but these did not show up as significant predictors.

Can you summarise all that?

- Compared to other cities, Sydney has many more clusters and they are larger, more dense, and generally have much lower private transport mode shares.

- With the exception of Canberra, less than half of all jobs in each city were in either the inner city area or a dense suburban jobs cluster. In Perth it was as low as 32%, while Sydney was 45%, and Canberra 54%.

- Higher density clusters correlate with lower private transport mode shares.

- Only higher density clusters centred on train stations with strong connections to the broader train network achieve relatively high public transport mode shares of journeys to work.

- High quality bus services can boost mode shares in clusters, but the highest bus-only mode share was 15% (in 2016).

- High-frequency express shuttle bus services can boost public transport mode shares in off-rail clusters.

- Walk-only mode shares for journeys to work are generally very low (typically 2-5%) but generally higher in clusters where there are many nearby residents.

- Private transport mode shares are generally 90%+ in clusters with free parking.

- I suspect there is a relationship between parking prices and private mode share, but it’s hard to get complete data to prove this. Subsidised employer provided parking probably leads to higher private transport mode shares, and may be common at hospitals. However unexpectedly cheap parking in Bondi Junction and Chatswood needs to be explained (perhaps an oversupply, or just horrible traffic congestion?).

- There is some evidence to suggest hospitals are prone to having higher private transport mode shares, possibly due to significant numbers of shift workers who need to commute at times when public transport service levels are lower.

- Private transport shares in suburban clusters are much higher than central cities, but lower than elsewhere in cities. The private transport mode share of net new jobs in clusters is much higher than for central city areas, but generally lower than elsewhere in cities.

- High density clusters still have large amounts of car parking.

- Median commuter distances to suburban employment clusters are sometimes longer and sometimes shorter than median commuter distances to each cities CBD.

- The clusters of Joondalup, Clayton, Murdoch, and Bella Vista – Norwest – Castle Hill have grown significantly in size with very high private transport mode shares. These centres might be experiencing increased traffic congestion, and their growth might be limited without significant improvements in public transport access.

What could this mean for Melbourne’s “National Employment and Innovation Clusters”?

One motivation for this research was getting insights into the future of Melbourne’s National Employment and Innovation Clusters (NEICs). What follows is intended to be observations about the research, rather than commentary about the whether any plans should be changed, or certain projects should or should not be built.

Firstly, the “emerging” NEICs of Sunshine and Werribee didn’t meet my (arguably) low criteria for dense employment clusters in 2016 (too small). The same is true for the Dandenong South portion of the “Dandenong” cluster (not dense enough).

Parkville and Fishermans Bend would have qualified had I not excluded areas within 4km of the CBD.

Significant sections of the Parkville, Fishermans Bend, Dandenong, Clayton, and La Trobe NEICs are currently beyond walking distance of Melbourne’s rapid transit network. Of these currently off-rail clusters:

- Parkville: a new rail link is under construction

- Fishermans Bend: new light and heavy rail links are proposed. In the short term, paid parking is to be introduced in some parts in 2018 (which had commuter densities of 47-63 per hectare in 2016). The longer term vision is for 80% of transport movements by public or active transport.

- Clayton: New light and heavy rail links are proposed. The Monash University campus has had paid parking for some time, but there appears to be free parking for employees in the surrounding industrial areas to the north and east. It will be interesting to see if/when paid parking becomes a reality in the industrial area (commuter densities ranged from 48 to 74 jobs/ha in 2016, not dissimilar to Fishermans Bend). The Monash Medical Centre area is relatively close to Clayton train station, has very high commuter density (329 per hectare in 2016 before a new children’s hospital opened in 2017) and had 88% private transport mode share in 2016. No doubt car parking will be an ongoing challenge/issue for this precinct.

- La Trobe: No rapid transit links are currently proposed to the area around the university, which had an 83% private transport mode share in 2016. There is a currently a frequent express shuttle bus from Reservoir station to the university campus, and a high frequency tram route touches the western edge of the campus.

- Dandenong South: The area is dominated by industrial rather than office facilities, and the job density ranges from 7 to 33 commuters per hectare, which is relatively low compared to the clusters in my study. There are no commercial car parks listed on Parkopedia so I assume pretty much all employees currently get free parking. No rapid transit stations are proposed for the area. The area is served by a few bus routes, including one high frequency SmartBus route, but 98% of new jobs between 2011 and 2016 were accounted for by private transport trips. This suggests it is difficult even for high-frequency (but non-rapid) public transport to complete with free parking in such areas.

Another potential challenge is connectivity to Melbourne’s broader train network. Parkville (and Fishermans Bend should Melbourne Metro 2 be built) will be well connected to the broader network by the nature of their central location. The area around Sunshine station has excellent rail access from four directions (with a fifth proposed with Melbourne Airport Rail). Dandenong, La Trobe and Werribee are on or near 1 or 2 radial train lines.

You can read more about Melbourne’s employment clusters in this paper by Prof John Stanley, Dr Peter Brain, and Jane Cunningham, which suggests there would be productivity gains from improved public transport access to such clusters.

I hope this post provides some food for thought.

Posted by chrisloader

Posted by chrisloader