[Updated 29 March 2024: Capital city per-capita charts updated using estimated residential population data for June 2023]

What’s the latest data telling us about transport trends in Australia?

The Australian Bureau of Infrastructure and Transport Research Economics (BITRE) have recently published their annual yearbook full of numbers, and this post aims to turn those (plus several other data sources) into information and insights about the latest trends in Australian transport.

This is a long and comprehensive post (67 charts) covering:

- vehicle kilometres travelled

- passenger kilometres travelled

- public transport patronage (new this year)

- public transport mode share

- road deaths (new this year)

- freight volumes and mode split

- driver’s licence ownership

- car ownership

- vehicle fuel types (new this year)

- motor vehicle sales (new this year)

- emissions

- transport consumer costs

I’ve been putting out similar posts in past years, and commentary in this post will mostly be around recent year trends. See other similar posts for a little more discussion around historical trends (December 2022, January 2022, December 2020, December 2019, December 2018).

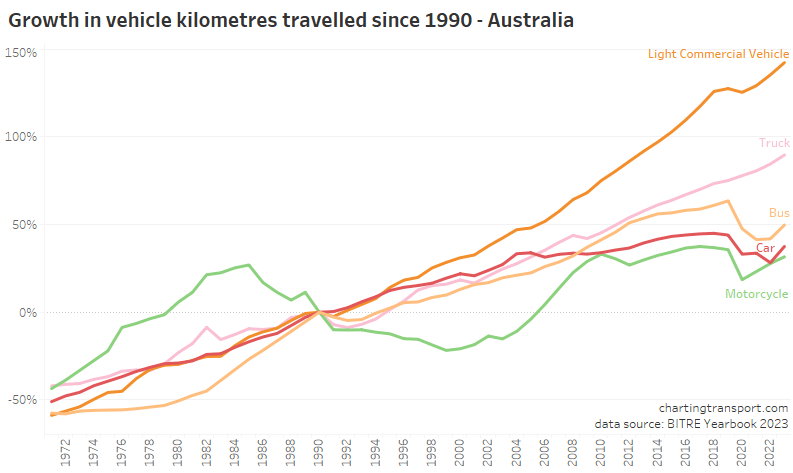

Vehicle kilometres travelled

Vehicle and passenger kilometre figures were significantly impacted by COVID lockdowns in 2020 and 2021 which has impacted financial years 2019-20, 2020-21, and 2021-22. Data is now available for 2022-23, the first post-pandemic year without lock downs.

Total vehicle kilometres for 2022-23 bounced back but were still lower than 2018-19:

The biggest pandemic-related declines in vehicle kilometres were in cars, motorcycles, and buses:

All modes showed strong growth in 2022-23.

Here’s the view on a per-capita basis:

Vehicle kilometres per capita peaked around 2004-05 and were starting to flatline in some states before the pandemic hit with obvious impacts. In 2022-23 vehicle kilometres per capita increased in all states and territories except the Northern Territory and Tasmania.

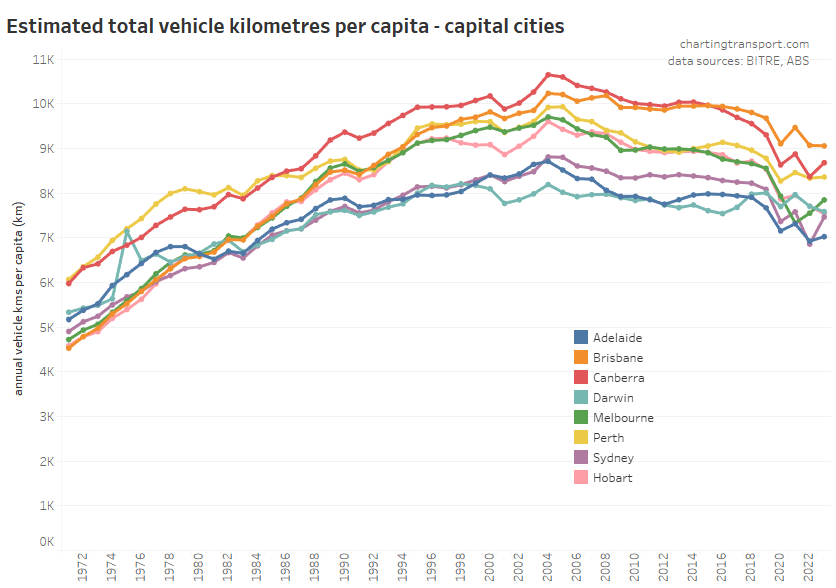

Here is the same data for capital cities:

Cities with COVID lockdowns in 2021-22 (Melbourne, Sydney, Canberra) bounced up in 2022-23, while Brisbane and Perth were relatively flat, Adelaide was slightly up, and Darwin slightly down. All large cities are still well below 2018-19 levels, consistent with an underlying long-term downwards trend.

Canberra has dramatically reduced vehicle kilometres per capita since around 2014 leaving Brisbane as the top city.

Passenger kilometres travelled

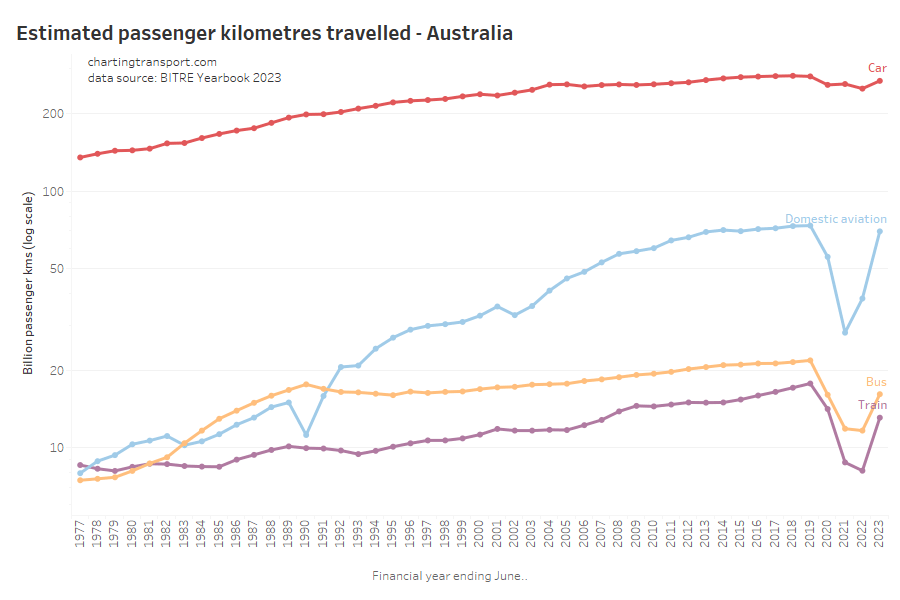

Here are passenger kilometres travelled overall (log scale):

The pandemic had the biggest impact on rail, bus, and aviation passenger kilometres. Aviation has bounced back to pre-COVID levels while train and bus are still down (probably due to working from home patterns, reduced total bus vehicle kilometres, amongst other reasons).

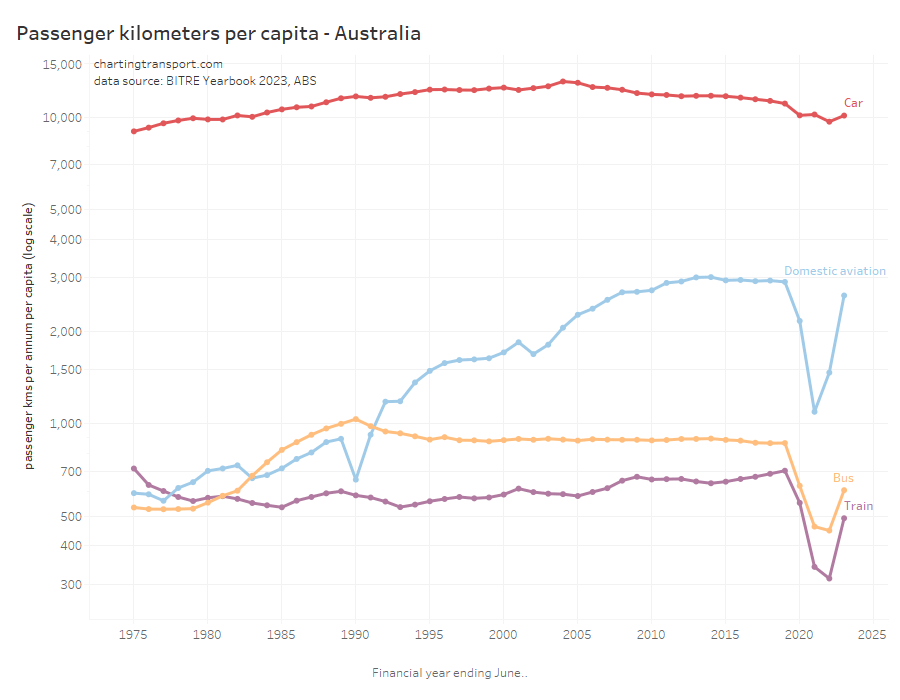

Here is the same on a per-capita basis which shows very similar patterns (also a log scale):

Car passenger kilometres per capita have reduced from a peak of 13,113 in 2004 to 10,152 in 2023.

Curiously aviation passenger kilometres per capita peaked in 2014, well before the pandemic. Rail passenger kilometres per capita in 2019 were at the highest level since 1975.

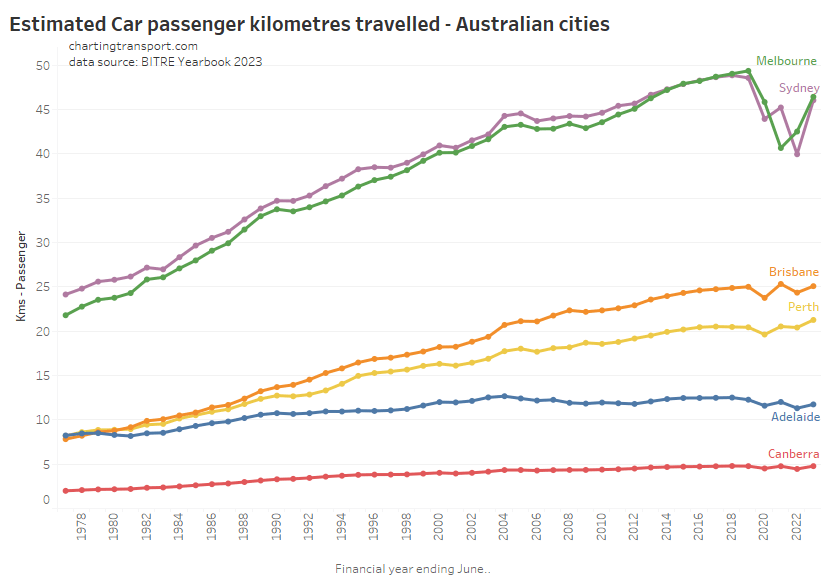

Here’s total car passenger kilometres for cities:

The COVID19 pandemic certainly caused some fluctuations in car passenger volumes in all cities for 2019-20 to 2021-22. In 2022-23, Sydney and Melbourne had not recovered to pre-pandemic levels, while Perth hit a new high.

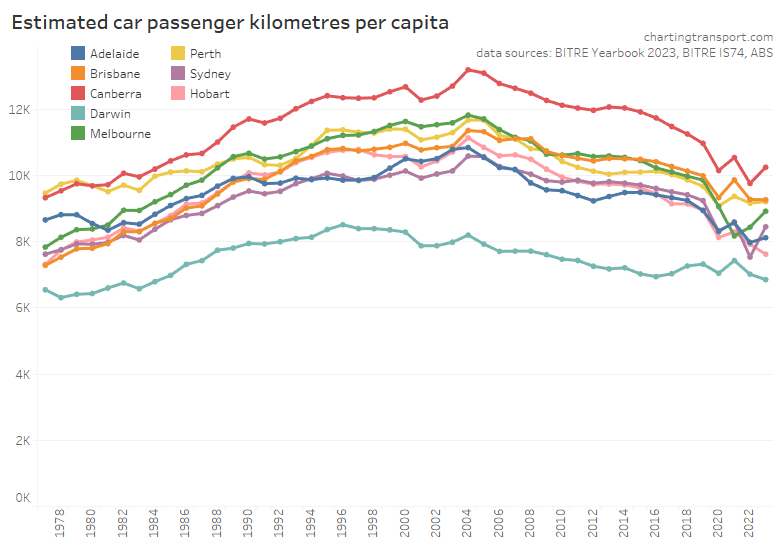

Here are per capita values for cities:

Car passenger kilometres per capita bounced back in Sydney, Melbourne, and Canberra – however most cities had 2022-23 figures that were in line with a longer-term downward trend – if you disregard the COVID years.

Public transport patronage

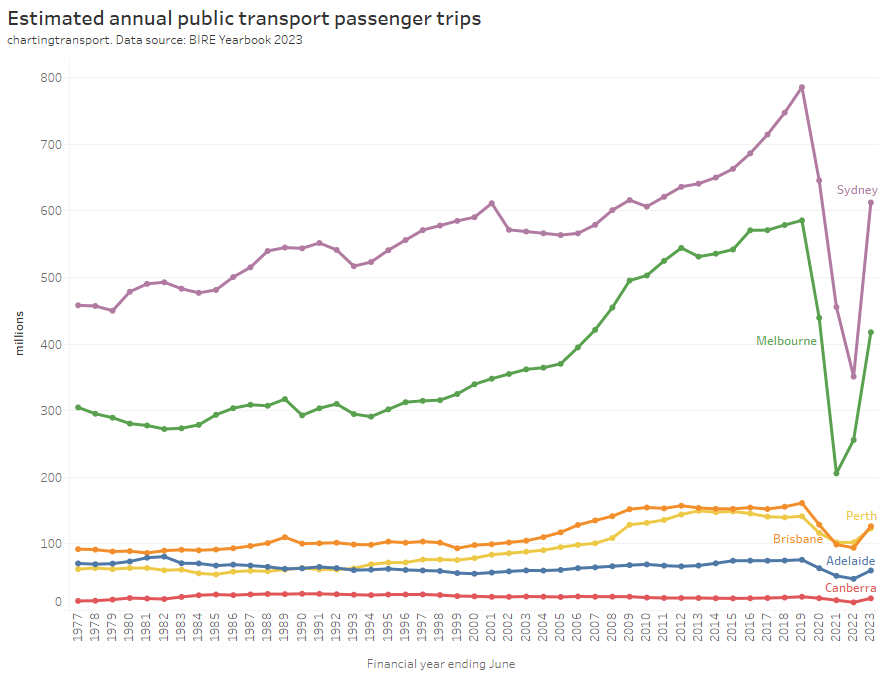

BITRE are now reporting estimates of public transport passenger trips (as well as estimated passenger kilometres). From experience, I know that estimating and reporting public transport patronage is a minefield especially for boardings that don’t generate ticketing transactions. While there are not many explanatory notes for this data, it appears BITRE have estimated capital city passenger boardings, which will be less than some ticketing region boardings (Sydney’s Opal ticketing region extends to the Illawarra and Hunter, and South East Queensland’s Go Card network includes Brisbane plus the Sunshine and Gold Coasts). I’ll report them as-is, but bear in mind that they might not be perfectly directly comparable between cities.

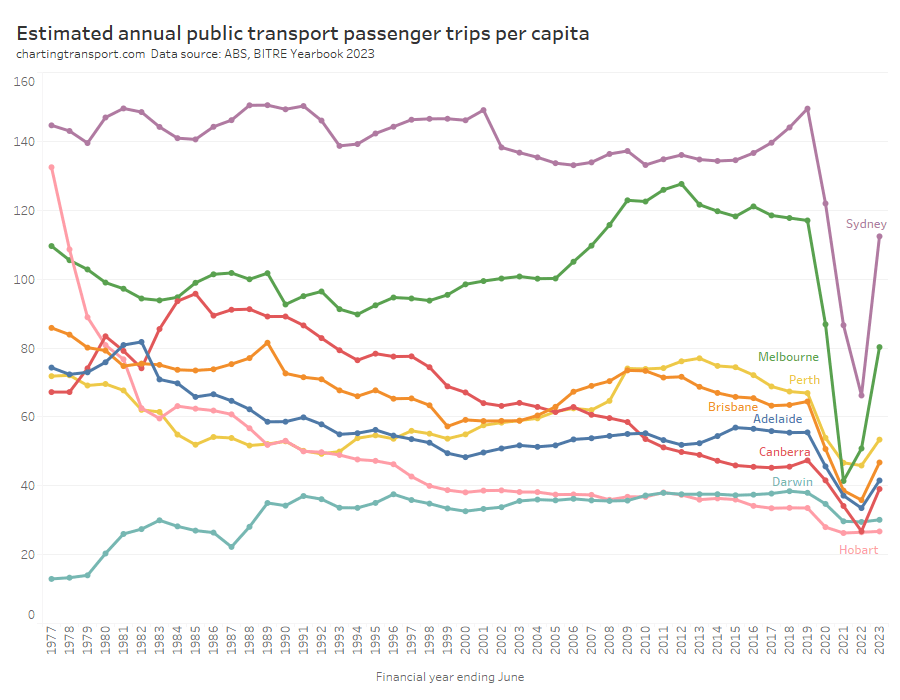

Of course bigger cities tend to generate more boardings, so it’s probably worth looking at passenger trips per capita per year:

This chart produces some unexpected outliers. Hobart shows up with very high public transport trips per capita in the 1970s, which might be relate to the Tasman Bridge Disaster which severed the bridge between 1975 and 1977 and resulted in significant ferry traffic for a few years (over 7 millions trips in 1976-77). Canberra also shows up with remarkably high trips per capita in the 1980s for a relatively small, low density, car-friendly city, but has been in steady decline since.

Canberra, Sydney, and Brisbane were seeing rising patronage per capita up to June 2019, just before the pandemic hit.

Most cities (except Darwin and Hobart), showed a strong bounce back in public transport trips per capita in 2022-23, although none reached 2018-19 levels.

There are further reasons why comparing cities is still not straight forward. Smaller cities such as Darwin, Canberra, and Hobart are almost entirely served by buses, and so most public transport journeys will only require a single boarding. Larger cities have multiple modes and often grid networks that necessitate transfers between services for many journeys, so there will be a higher boardings to journeys ratio. If a city fundamentally transforms its network design there could be a sudden change in boardings that doesn’t reflect a change in mode share.

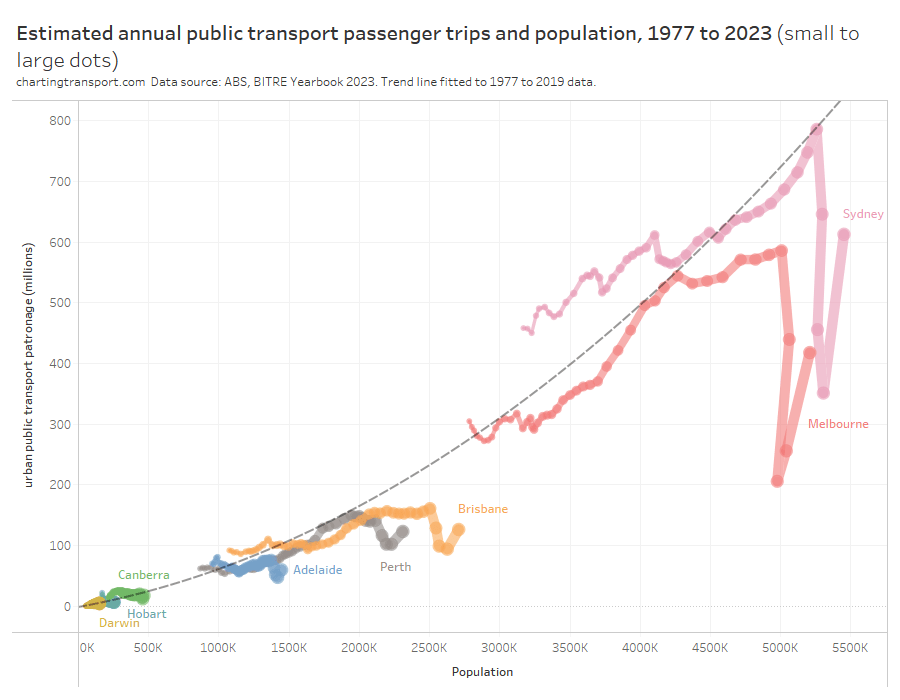

Indeed, here is the relationship between population and boardings over time. I’ve drawn a trend curve to the pre-pandemic data points only (up to 2019).

Larger cities are generally more conducive to high public transport mode share (for various reasons discussed elsewhere on this blog) but also often require transfers to facilitate even radial journeys.

So boardings per capita is not a clean objective measure of transit system performance. I would much prefer to be measuring public transport passenger journeys per capita (as opposed to boardings) which might overcome the limitations of some cities requiring transfers and others not.

The BITRE data is reported as “trips”, but comparing with other sources it appears the figures are boardings rather than journeys. Most agencies unfortunately don’t report public transport journeys at this time, however boardings to journeys ratio could be estimated from household travel survey data for some cities.

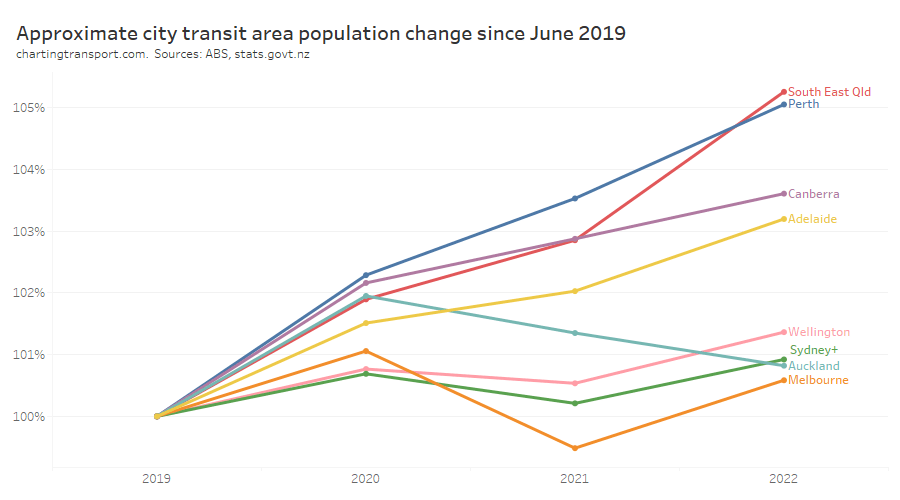

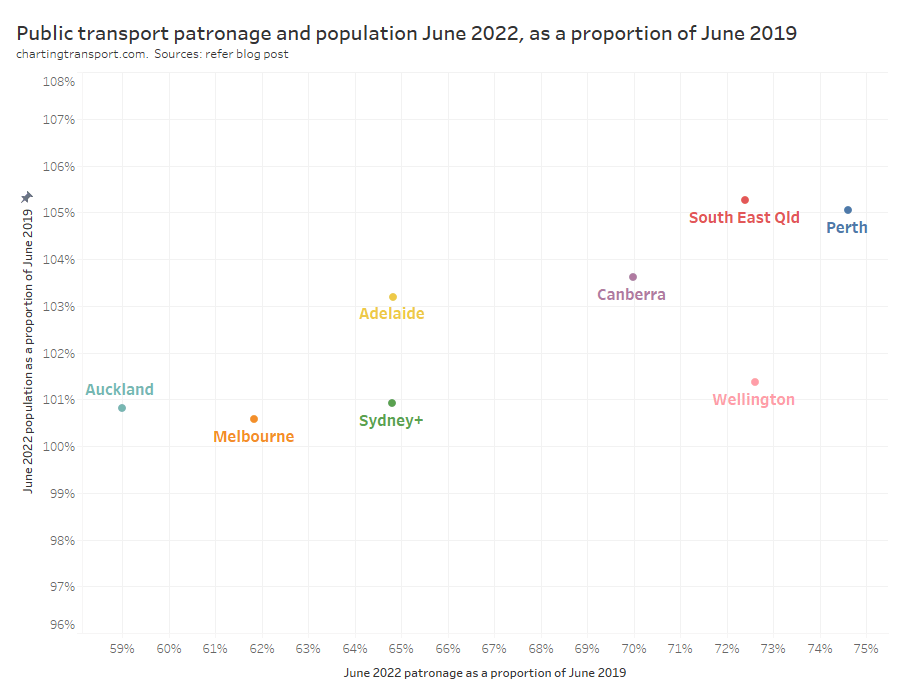

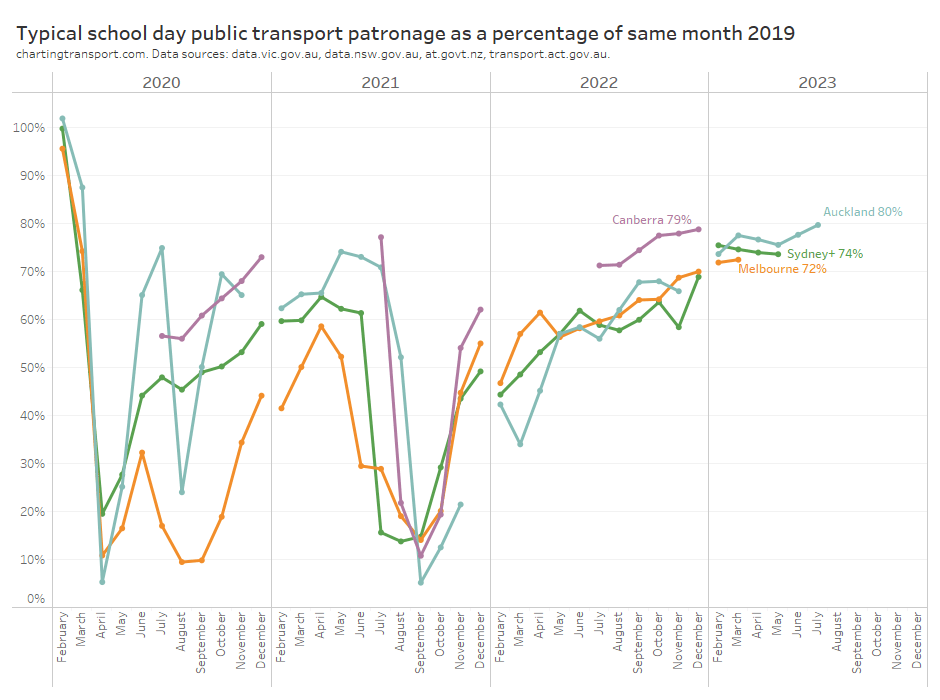

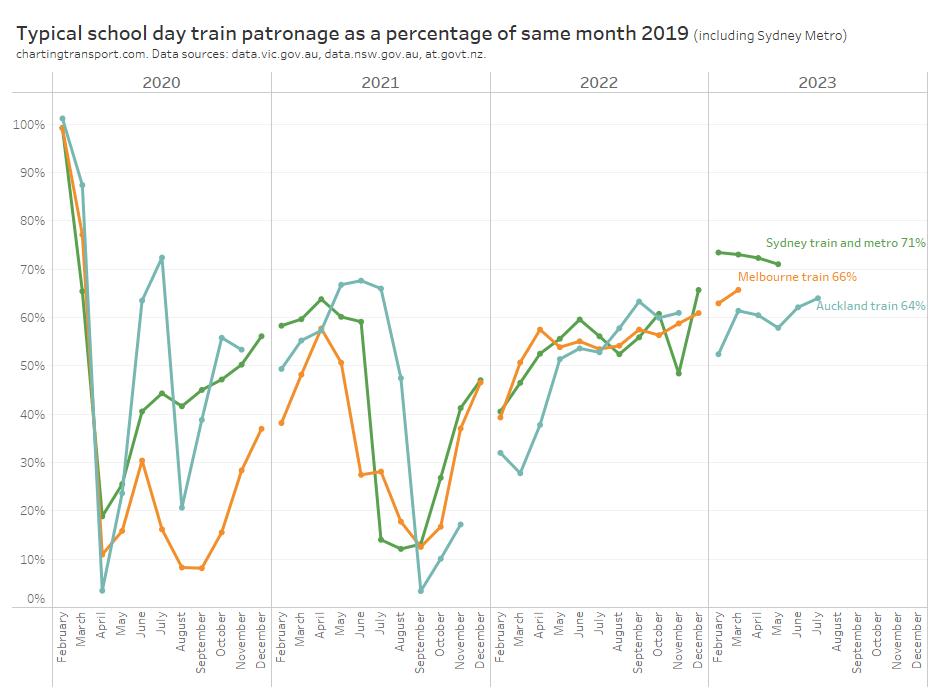

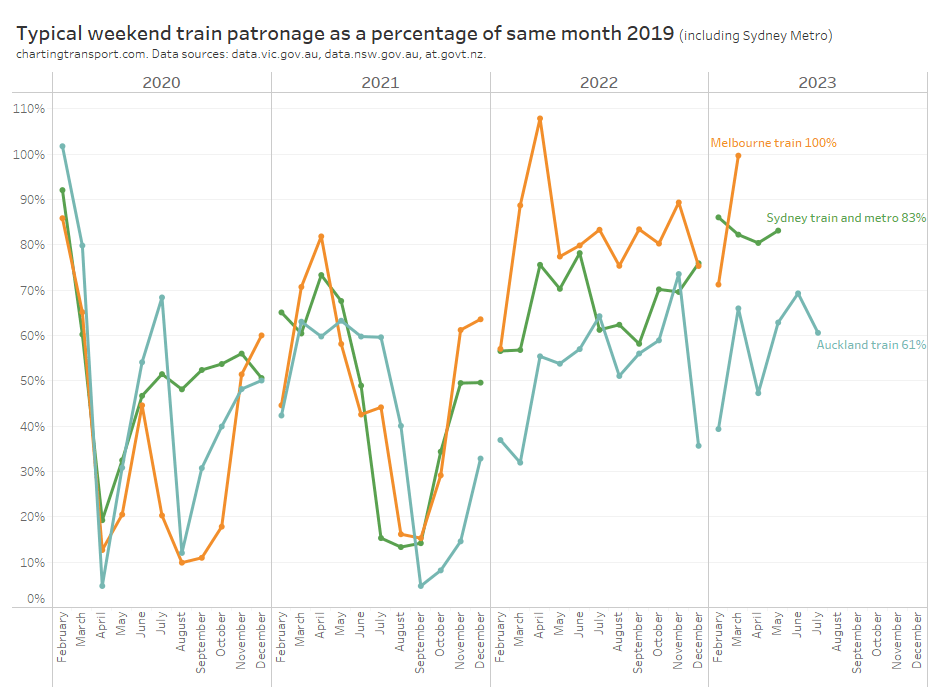

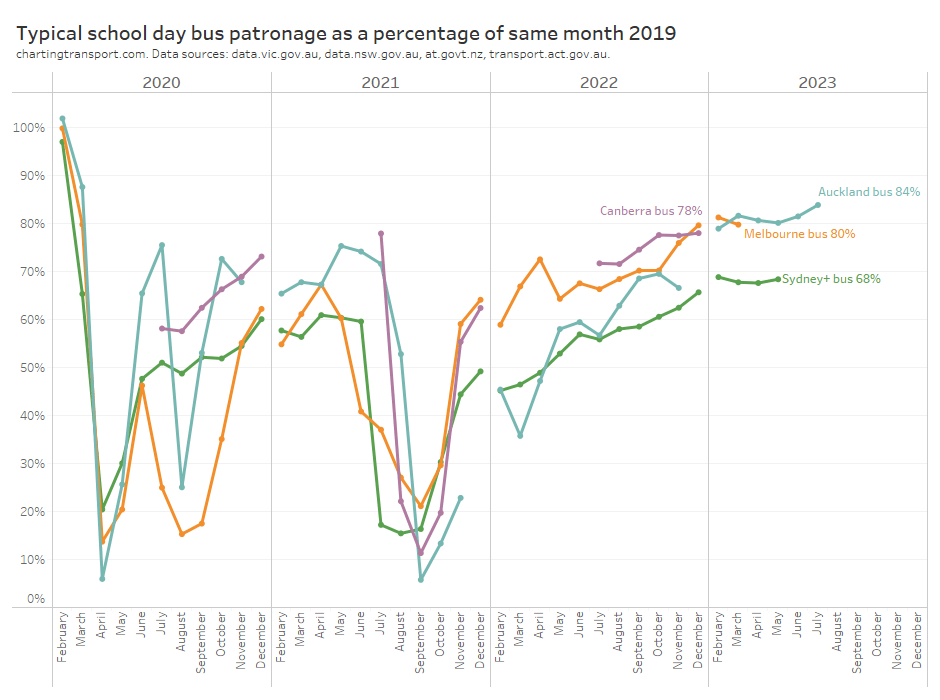

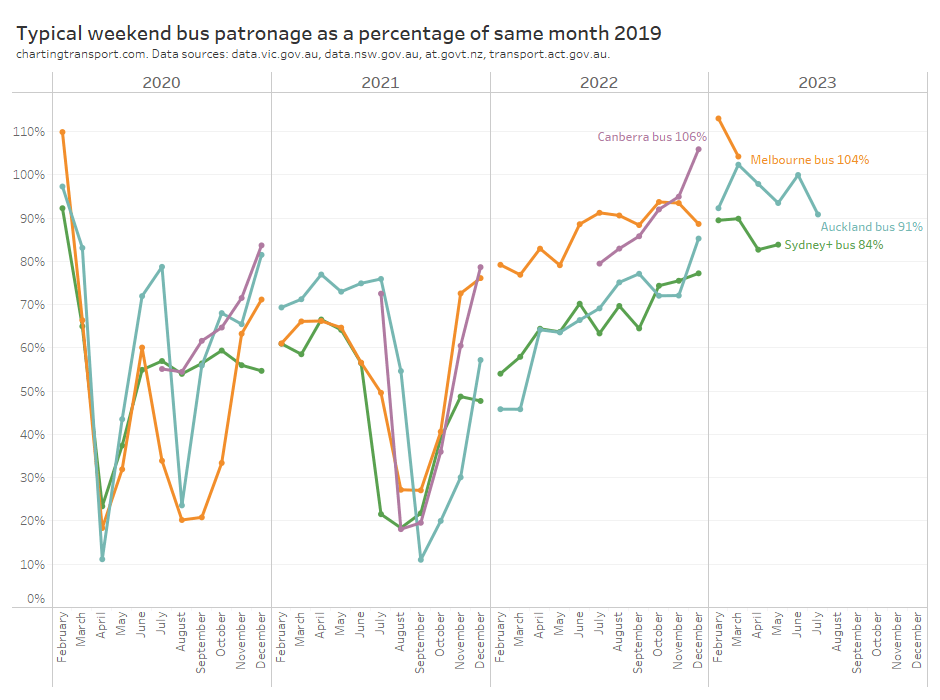

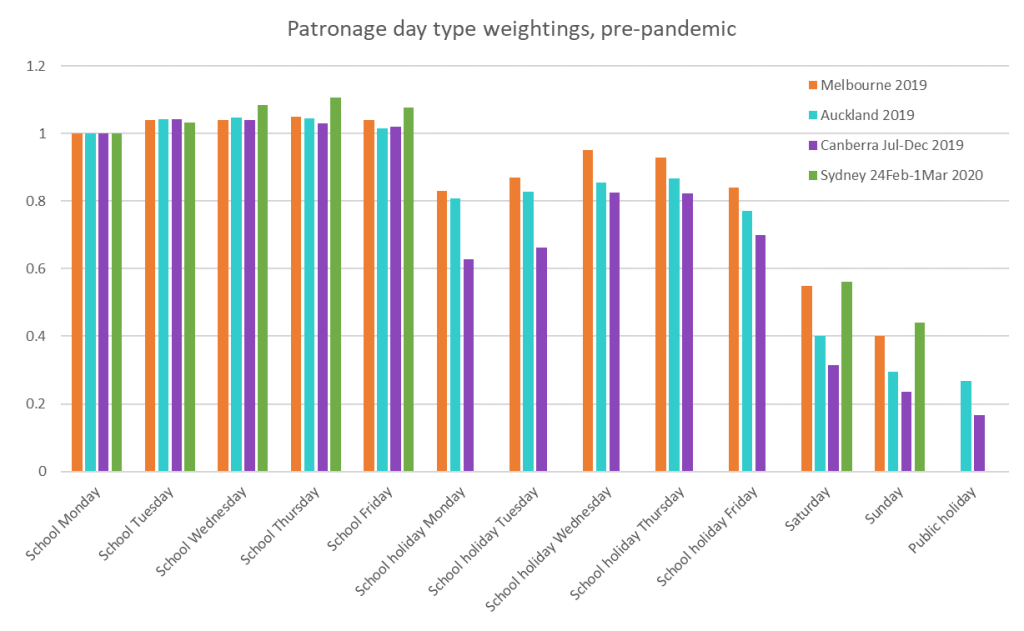

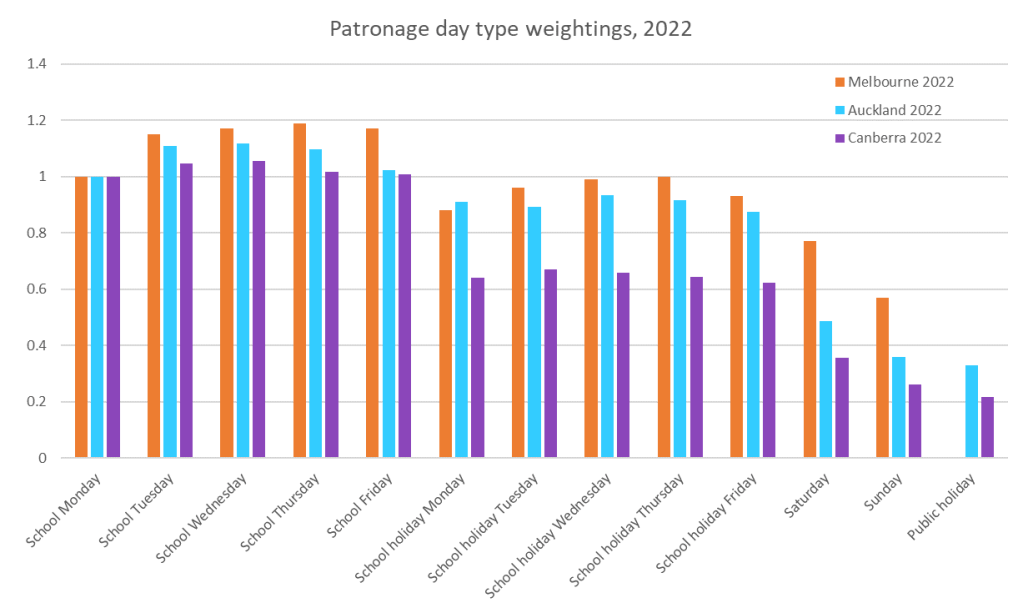

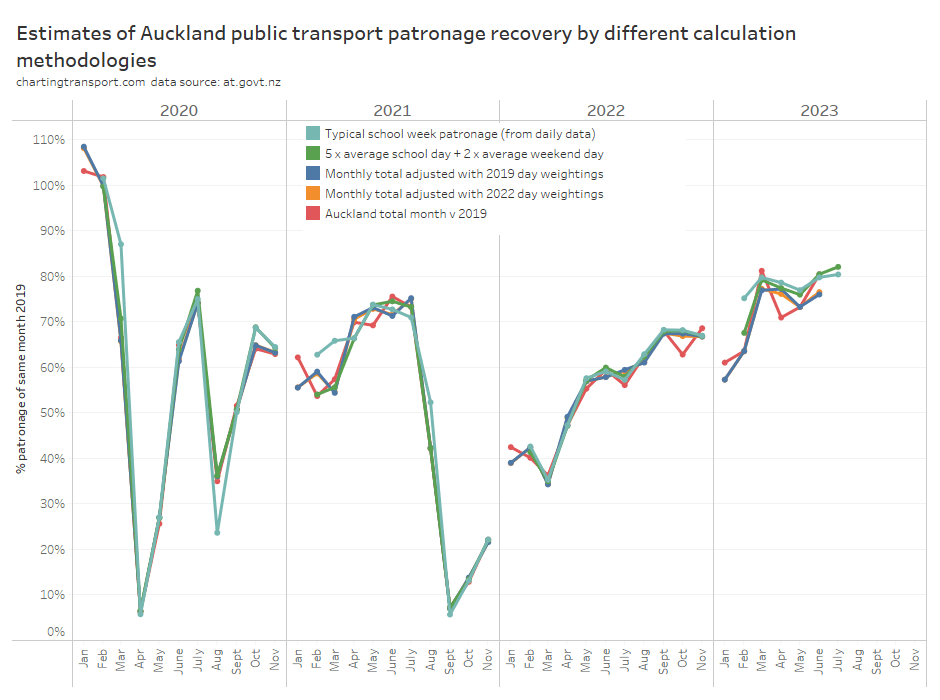

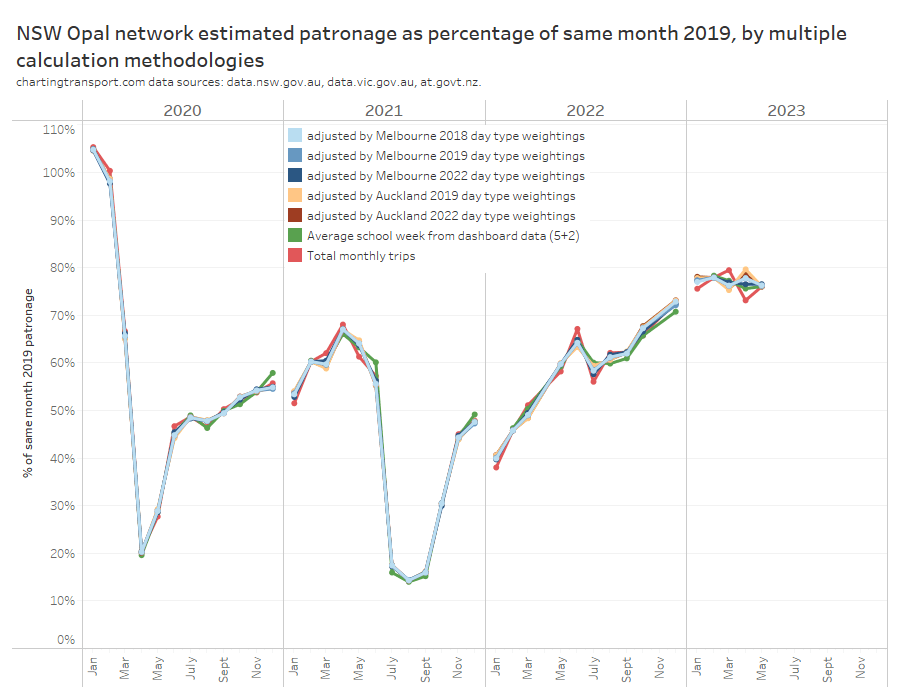

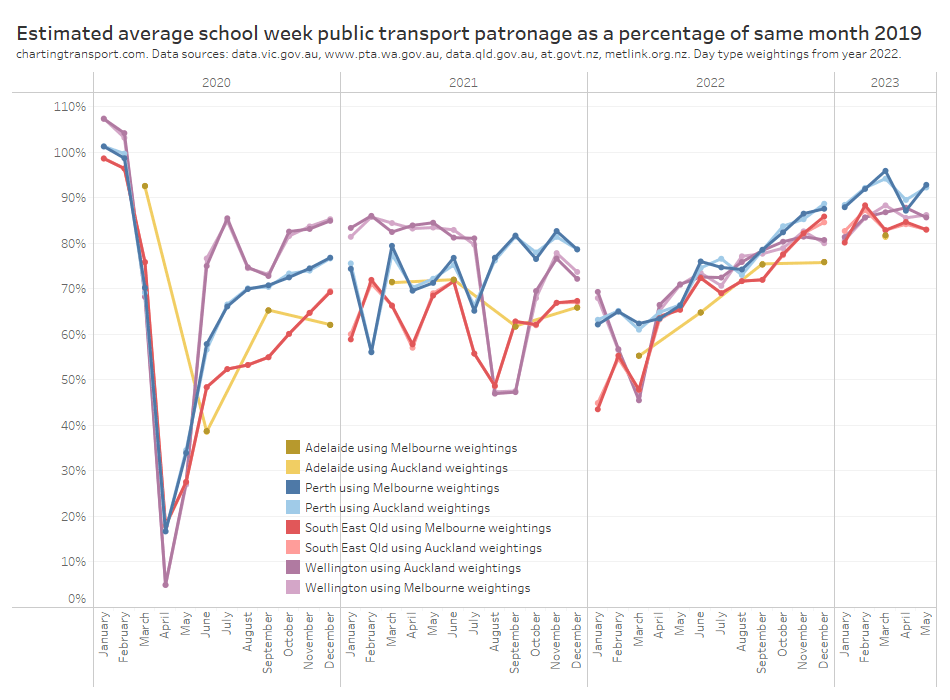

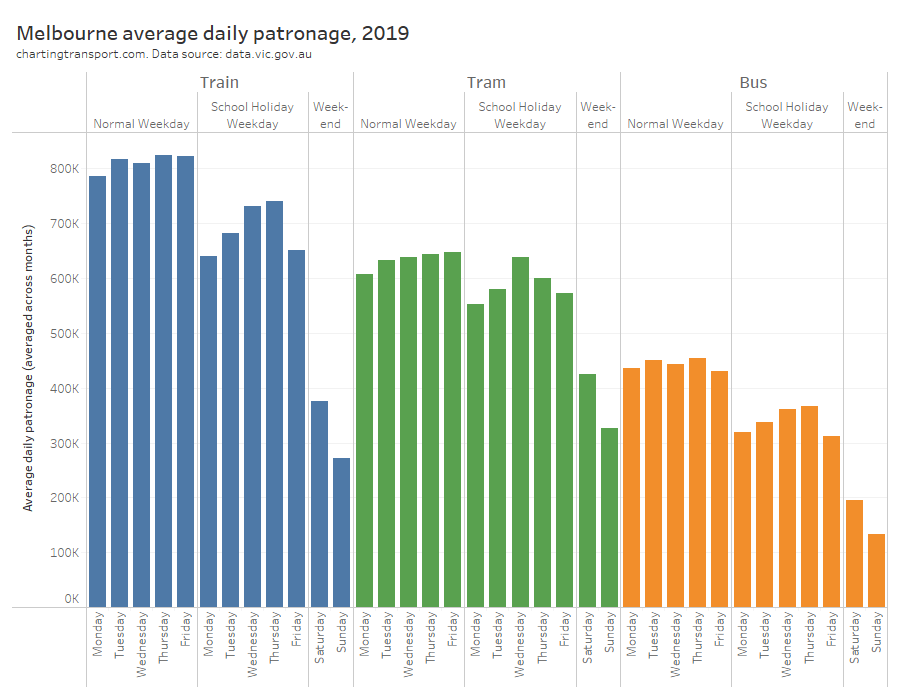

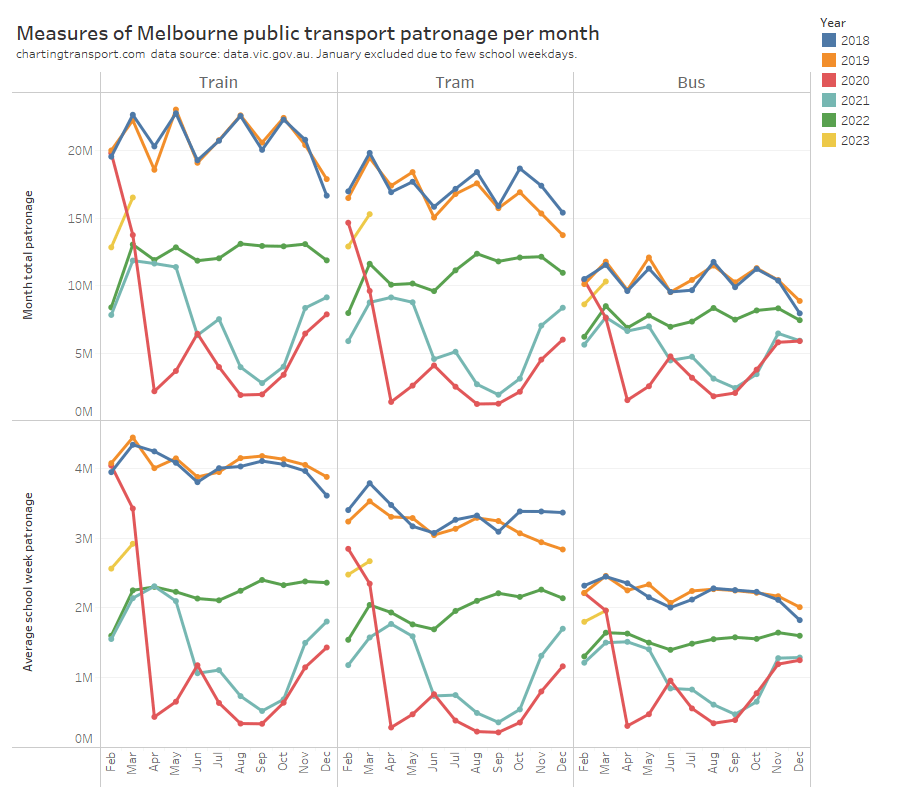

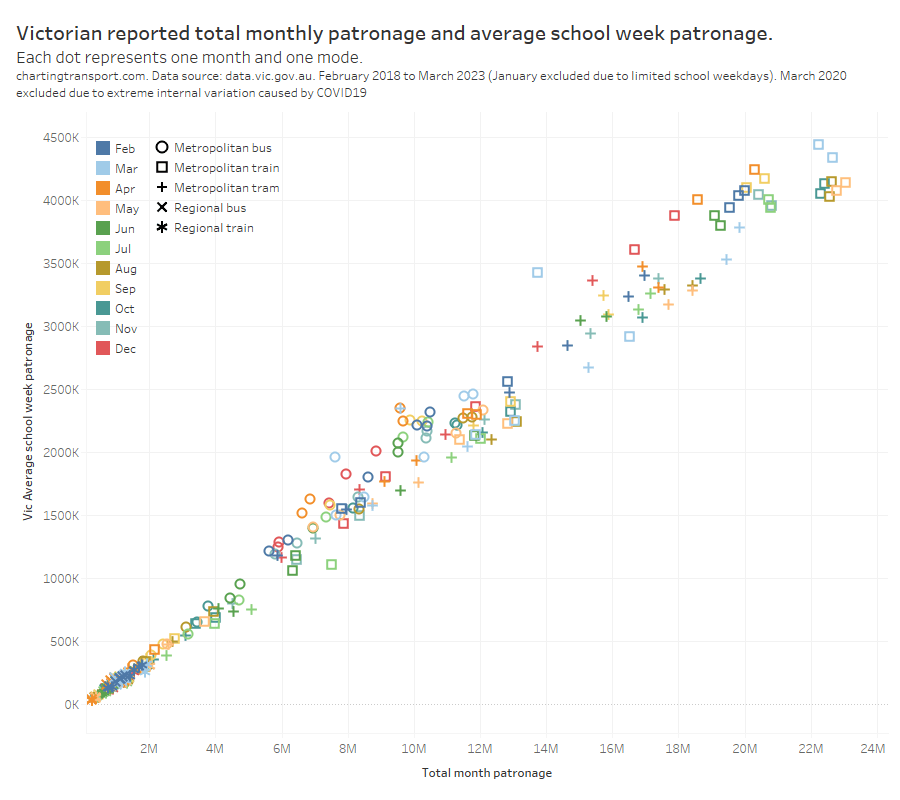

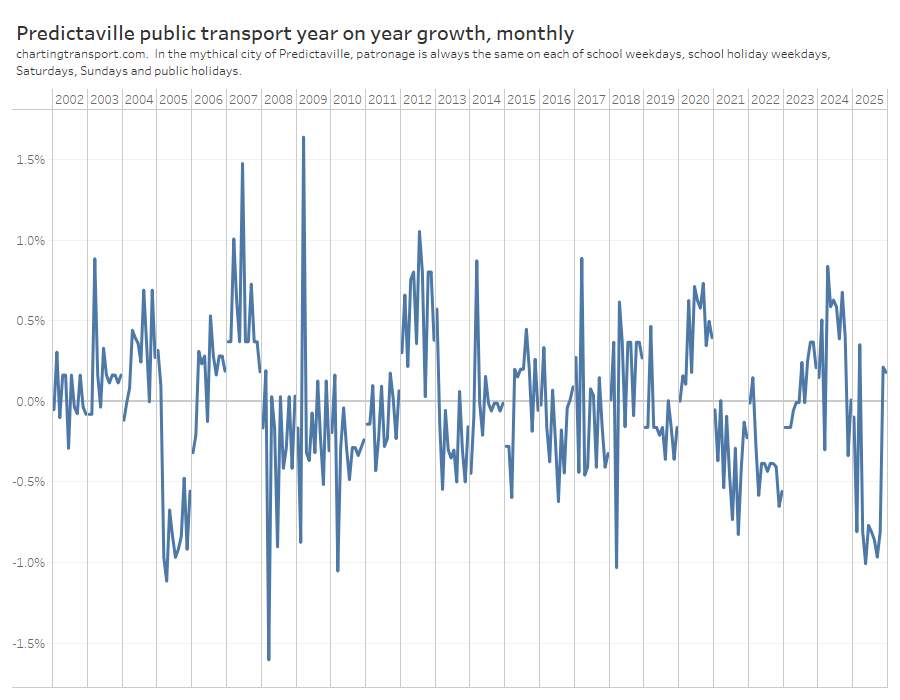

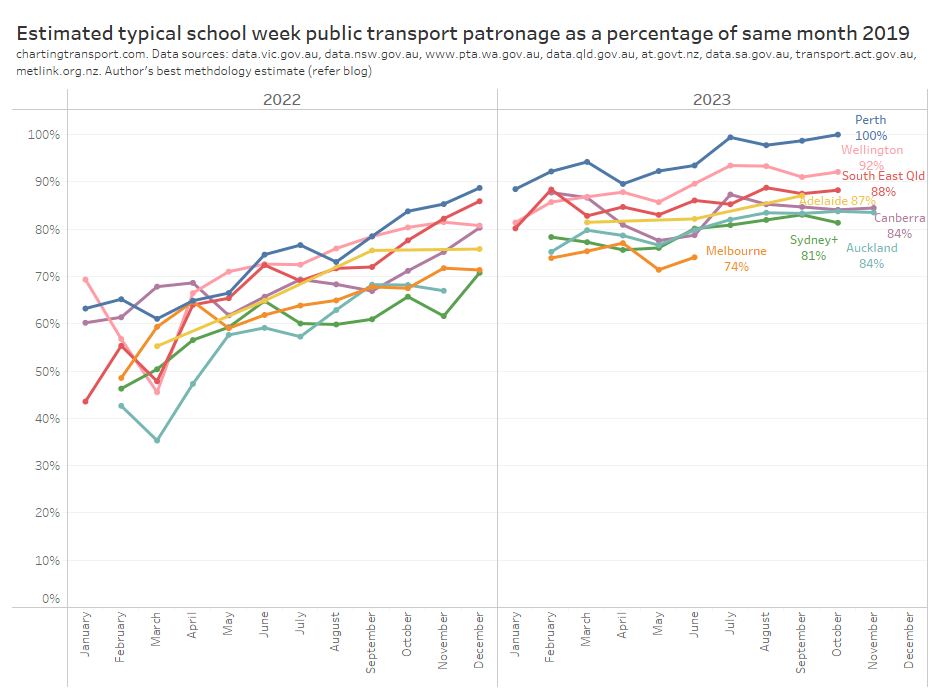

Public transport post-pandemic patronage recovery

I’ve been estimating public transport patronage recovery using the best available data for each city (as published by state governments – unfortunately the usefulness and resolution of data provided varies significantly, refer: We need to do better at reporting and analysing public transport patronage). This data provides a more detailed and recent estimate of patronage recovery compared to 2019 levels. Here’s the latest estimates at the time of preparing this post:

Perth seems to be consistently leading Australian and New Zealand cities on patronage recovery, while Melbourne appears to be the laggard in both patronage recovery and timely reporting. For more discussion and details around these trends see How is public transport patronage recovering after the pandemic in Australian and New Zealand cities?.

[refer to my twitter feed for more recent charts]

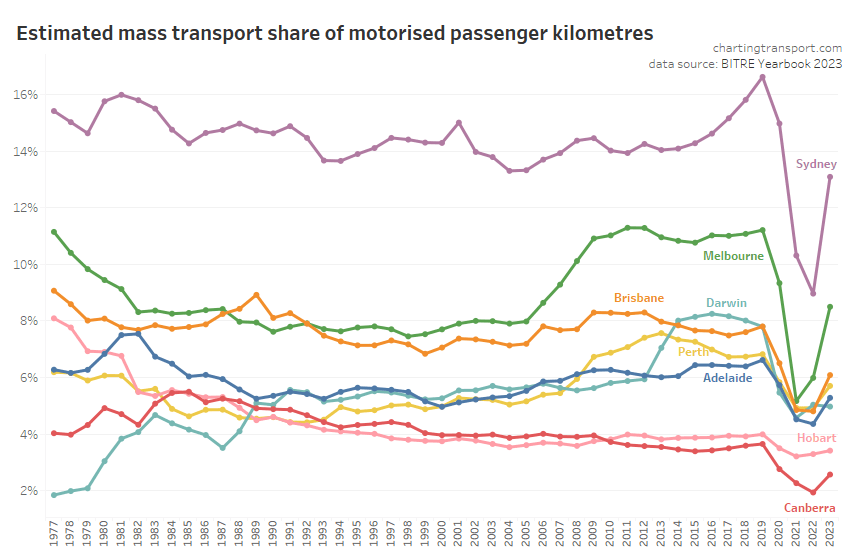

Passenger travel mode split

It’s possible to calculate “mass transit” mode share using the passenger kilometres estimates from BITRE (note: I use “mass transit” as BITRE do not differentiate between public and private bus travel):

Mass transit mode shares obviously took a dive during the pandemic, but have since risen, although not back to 2019 levels – presumably at least partly because of working from home.

The relative estimates of share of motorised passenger kilometres are quite different to the estimates of passengers trips per capita we saw just above. Canberra is much lower than the other cities, and Brisbane and Melbourne are closer together. The passenger kilometre estimates rely on data around average trip lengths (which is probably not regularly measured in detail in all cities), while the passenger boardings per capita figures are subject to varying transfer rates between cities. Neither are perfect.

So what else is there? I have been looking at household travel survey data to also calculate public transport mode share, but I am getting unexpected results that are quite different to BITRE estimates (especially Melbourne) and with unexpected trends over time (especially Brisbane), so I’m not comfortable to publish such analysis at this point.

What would be excellent is if agencies published counts of passenger journeys (that might involve multiple boardings), so we could compare cities more readily.

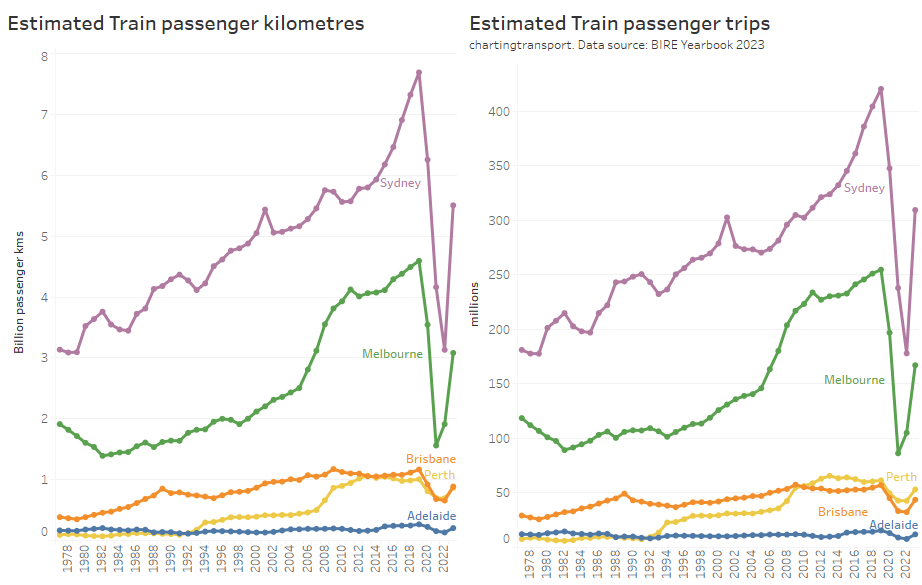

Rail Passenger travel

Here’s a chart showing estimates of annual train passenger kilometres and trips.

All cities are bouncing back after the pandemic.

Note there are some variances between the ranking of the cities – particularly Perth and Brisbane (BITRE have average train trip length in Brisbane at around 20.3 km while Perth is 16.3 km).

Here’s rail passenger kilometres per capita, but only up to 2021-22:

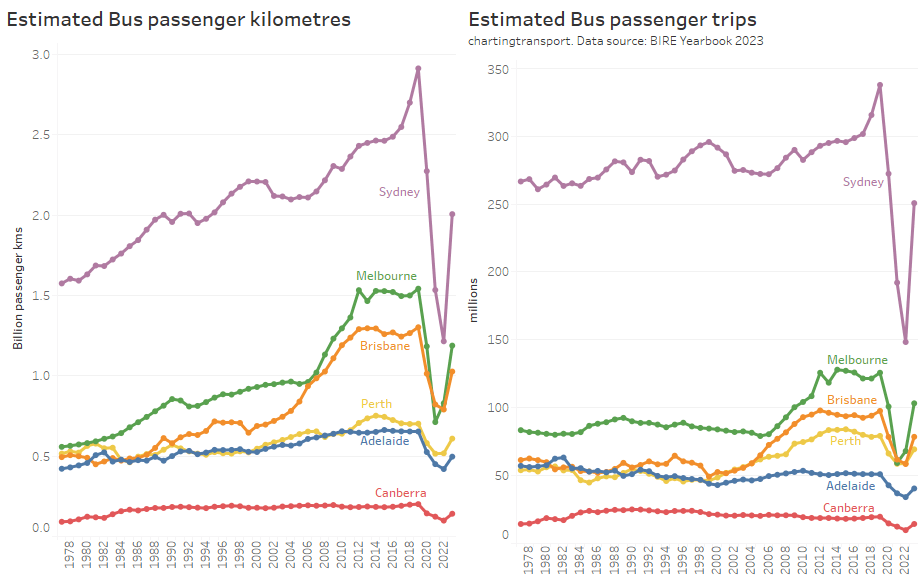

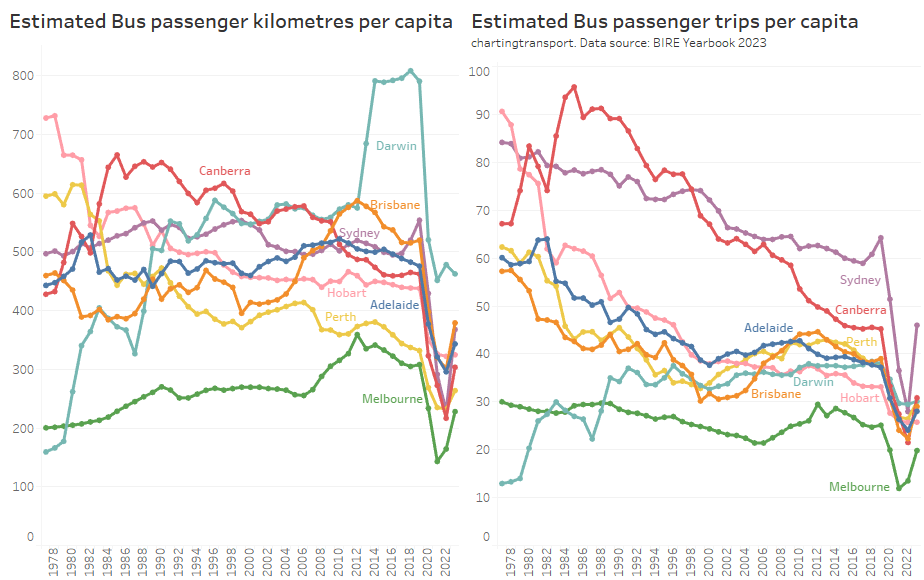

Bus passenger travel

Here’s estimates of total bus travel for capital cities:

And per capita bus travel up to 2021-22:

Note that Melbourne has the second highest volume of bus travel (being a large city), but the lowest per-capita usage of buses, primarily because – unlike most other cities – trams perform most of the busy on-street public transport task in the inner city. It probably doesn’t make sense to directly compare cities for bus patronage per capita, and indeed I won’t show such figures for the other public transport modes.

Darwin had elevated bus passenger kilometres from 2014 to 2019 due to bus services to a resources project (BITRE might not have counted these trips as urban public transport).

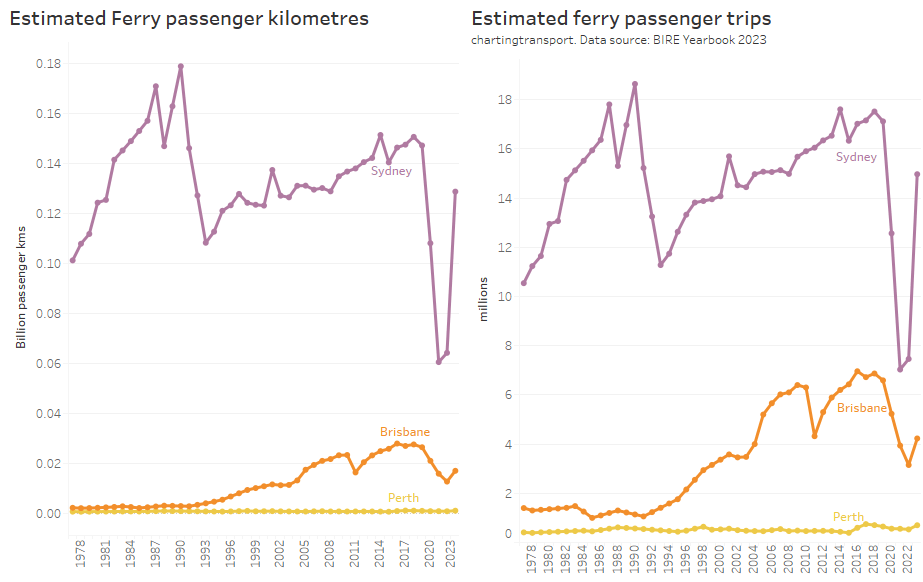

Ferry passenger travel

Sydney ferry patronage has almost recovered to pre-pandemic levels, while Brisbane’s ferries have not (as at 2022-23).

Light rail / tram passenger travel

Sydney light rail patronage is now growing strongly – after two new lines opened a few months before the pandemic hit.

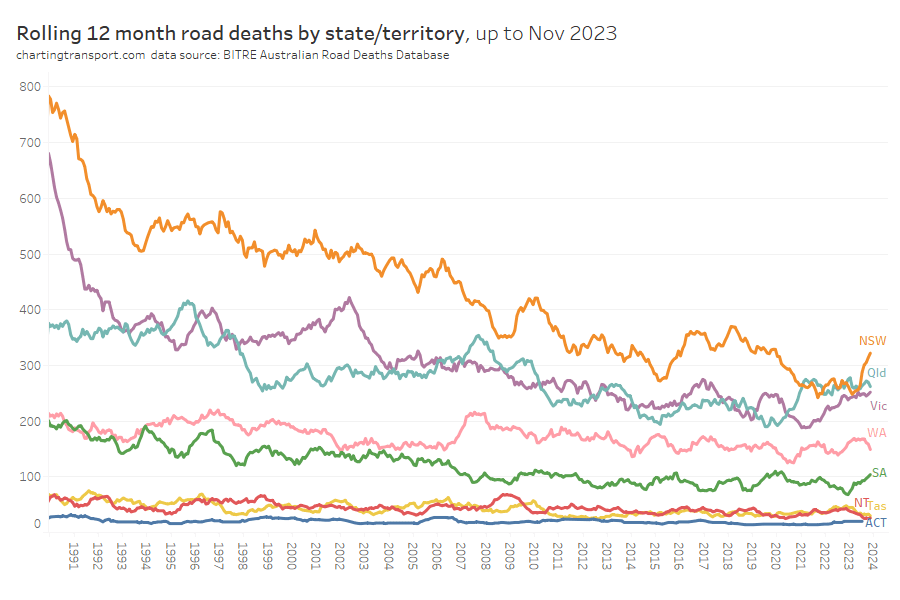

Road deaths

In recent months there has been an uptick in road deaths in NSW and SA. Victorian road deaths dropped during the pandemic but are back to pre-pandemic levels.

It’s hard to compare total deaths between states with very different populations, so here are road deaths per capita, for financial years:

There is naturally more noise in this data for the smaller states and territories as the discrete number of trips in these geographies is small. The sparsely populated Northern Territory has the highest death rate, while the almost entirely urban ACT has the lowest death rate.

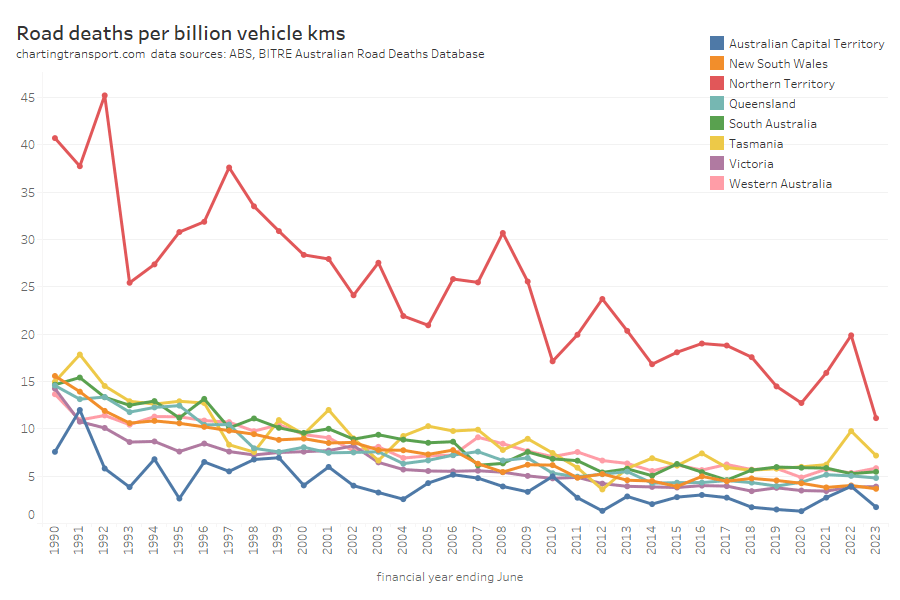

Another way of looking at the data is deaths per vehicle kilometre:

This chart is very similar – as vehicle kilometres per capita haven’t shifted dramatically.

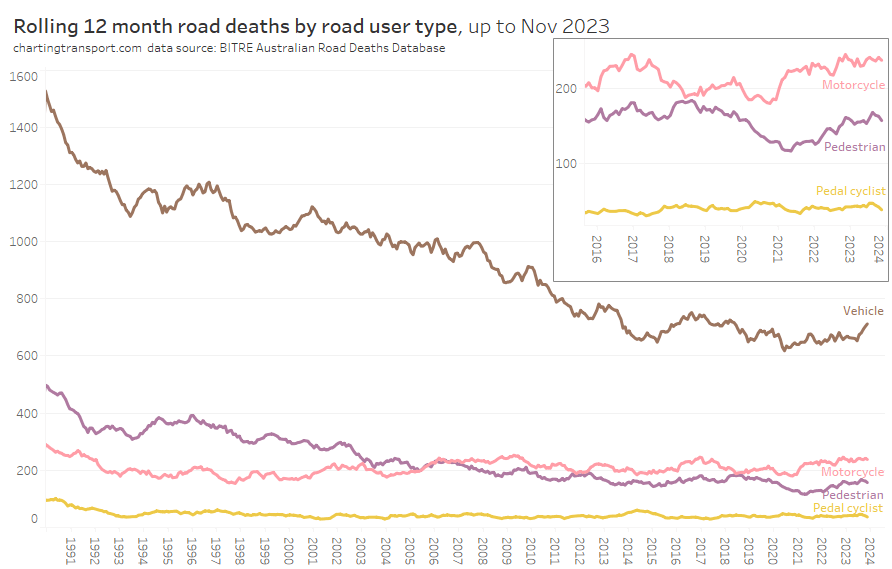

Next is road deaths by road user type, including a close up of recent years for motorcycles, pedestrians, and cyclists. I’ve not distinguished between drivers and and passengers for both vehicles and motorcycles.

Vehicle occupant fatalities were trending down until around 2020. Motorcyclist fatalities have been relatively flat for a long time but have risen slightly since 2021.

Pedestrian fatalities were trending down until around 2014 and have been bouncing up and down since (perhaps a dip associated with COVID lock downs).

Cyclist fatalities have been relatively flat since the early 1990s (apart from a small peak in 2014).

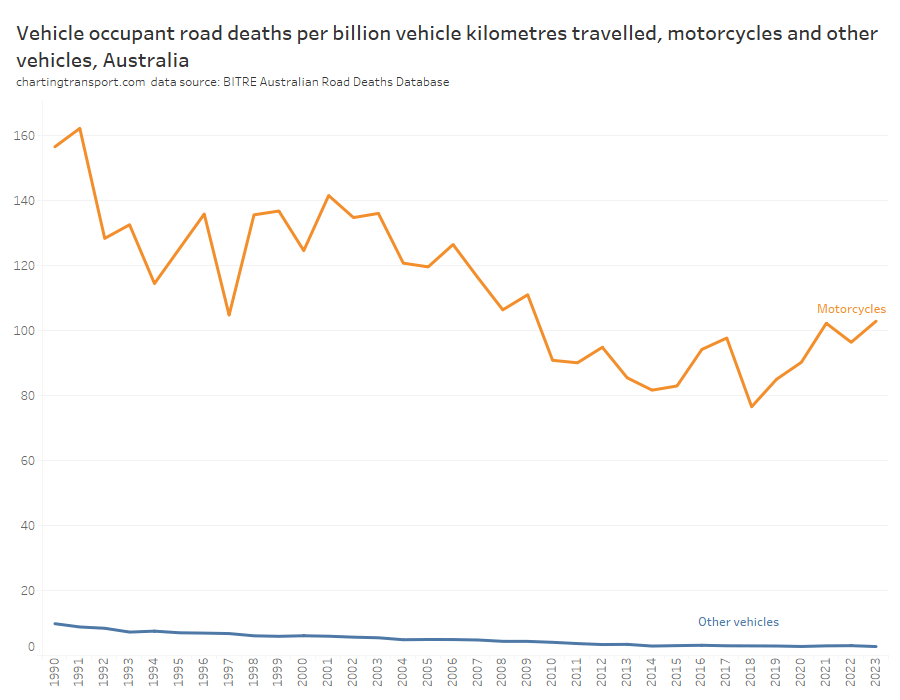

It’s possible to distinguish between motorcycles and other vehicles for both deaths and vehicle kilometres travelled, and the following chart shows the ratio of these across time:

The death rate for motorcycle riders and passengers per motorcycle kilometre was 38 times higher than other vehicle types in 2022-23. The good news is that the death rate for other vehicles has dropped from 9.8 in 1989-90 to 2.7 in 2022-23. The death rate for motorcycles was trending down from 1991 to around 2015 but has since risen again in recent years.

Freight volumes and mode split

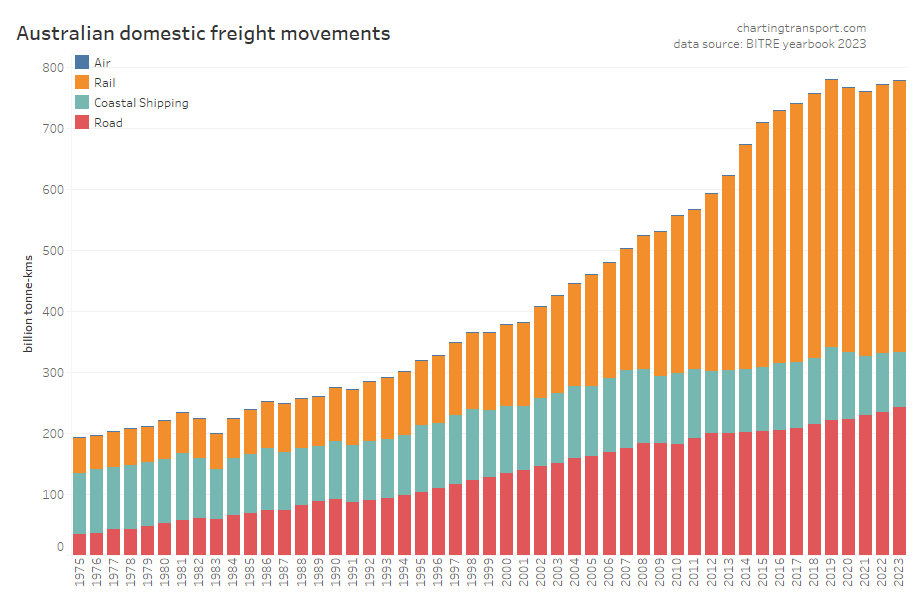

First up, total volumes:

This data shows a dramatic change in freight volume growth around 2019, with a lack of growth in rail volumes, a decline in coastal shipping, but ongoing growth in road volumes. Much of this volume is bulk commodities, and so the trends will likely be explained by changes in commodity markets, which I won’t try to unpack.

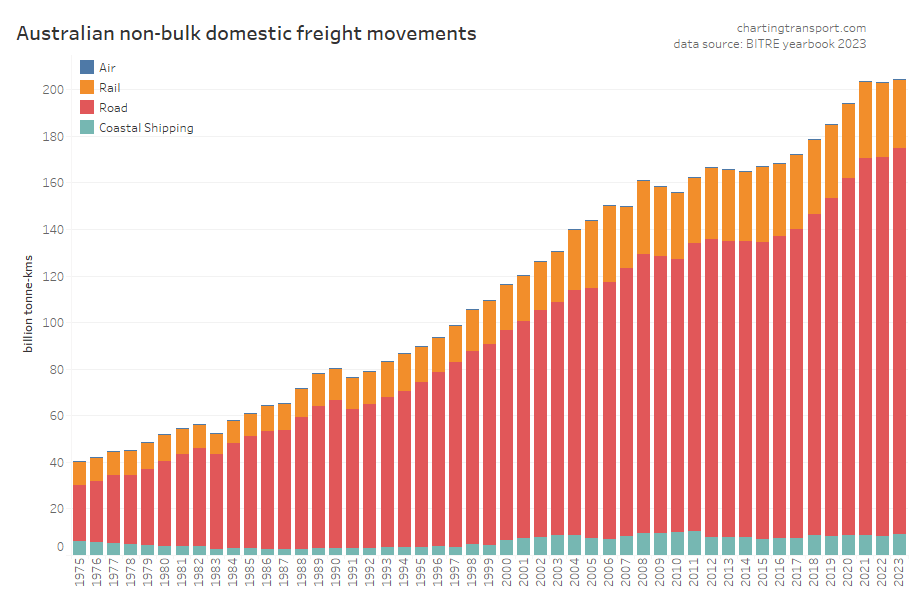

Non-bulk freight volumes are around a quarter of total freight volume, but are arguably more contestable between modes. They have flat-lined since 2021:

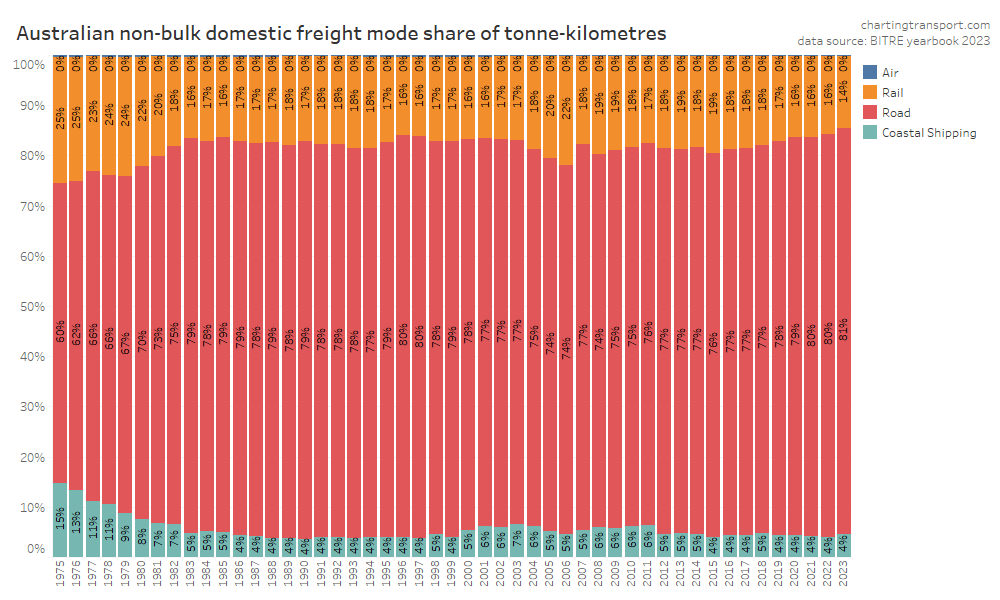

Here’s that by mode split:

In recent years road has been gaining mode share strongly at the expense of rail. This is a worrying trend if your policy objective is to reduce transport emissions as rail is inherently more energy efficient.

Air freight tonnages are tiny in the whole scheme of things so you cannot easily see them on the charts (air freight is only used for goods with very high value density).

Driver’s licence ownership

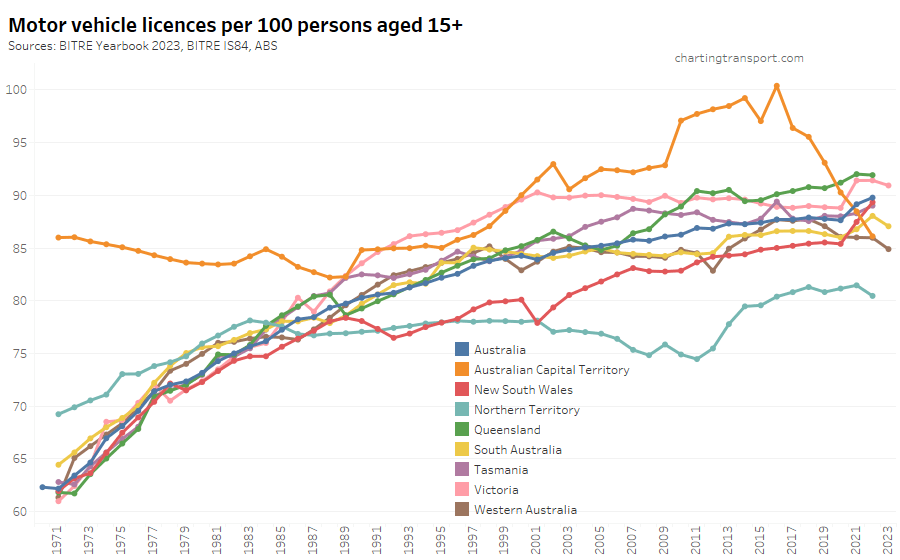

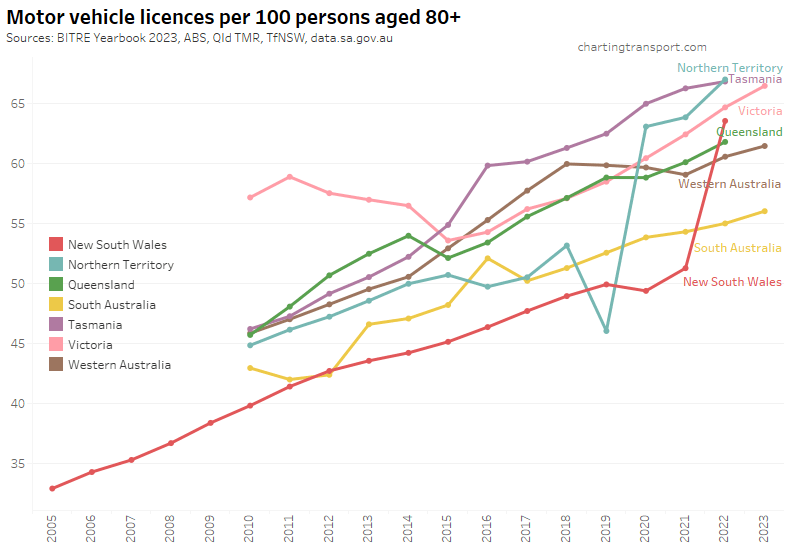

Here is motor vehicle licence ownership for people aged 15+ back to 1971 (I’d use 16+ but age by single-year data is only available at a state level back to 1982). Note this includes any form of driver’s licence including learner’s permits.

Technical note: the ownership rate is calculated as the sum of car, motorbike and truck licenses – including learner and probationary licences, divided by population. Some people have more than one driver’s licence so it’s likely to be an over-estimate of the proportion of the population with any licence.

Unfortunately data for June 2023 is only available for South Australia, Western Australia and Victoria, so we don’t know the latest trends in all states. South Australia and New South Wales regrettably appear to have recently stopped publishing useful licence holder numbers.

2023 saw a decline in licence ownership in the three states that reported. 2022 was a mixed bag with some states going up (NSW, South Australia, Tasmania), many flat, and the Northern Territory in decline.

Licence ownership rates have fluctuated in many states since the COVID19 pandemic hit, most notably in Victoria and NSW which saw a big uptick in 2021.

The data series for the ACT is unusually different in trends and values – with very high but declining rates in the 1970s, seemingly elevated rates from 2010 to around 2018, followed by a sharp drop. BITRE’s Information Sheet 84 (published in 2017) reports that ACT licences might remain active after people leave the territory (e.g. to nearby parts of NSW) because of delays in transferring their licences to another state, resulting in a mismatch between licence holder counts and population. However, New South Wales requires people to transfer their licence within 3 months of moving there, and other states likely do also. But that requirement might be new, changed, and/or differently enforced over time (please comment if you know more).

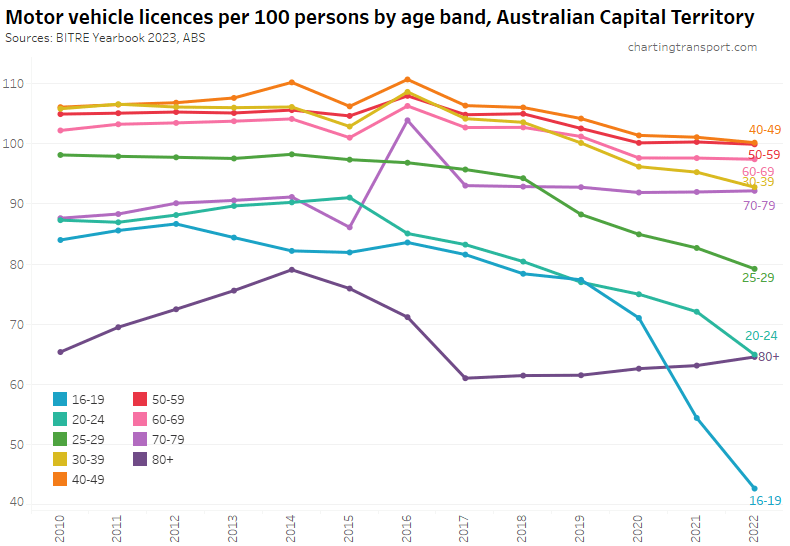

Here’s the breakdown of reported licence ownership by age band for the ACT:

Many age bands exceed 100 (more licence holders than population) and there are some odd kinks in the data around 2015-2017 for all age bands (especially 70-79). I’m not sure that it is plausible that licencing rates of teenagers might have plummeted quite so fast in recent years. I’m inclined to treat all of this ACT data as suspect, and I will therefore exclude the ACT from further charts with state/territory disaggregation.

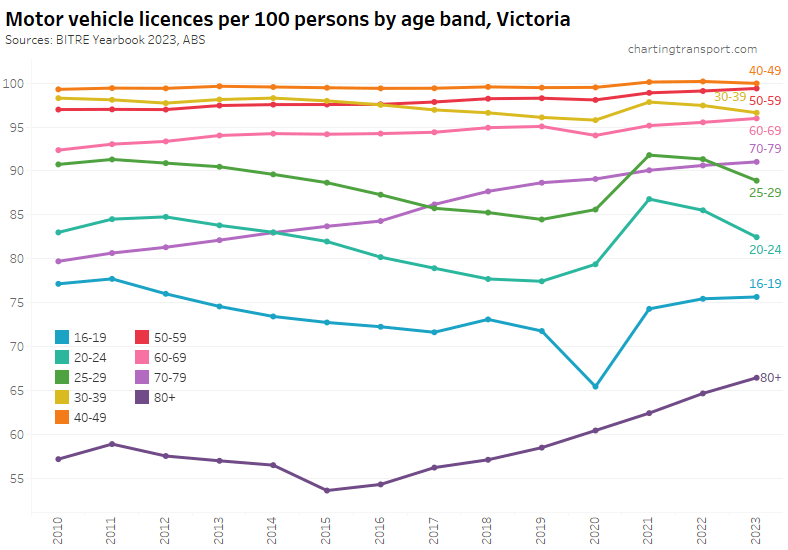

Here’s licence ownership by age band for Australia as a whole (to June 2022):

Between 2021 and 2022 ownership rates for 16-24 year-olds fell slightly, while ownership rates continued to rise for older Australians (quite dramatically for those 80 and over, mostly due to NSW, see below).

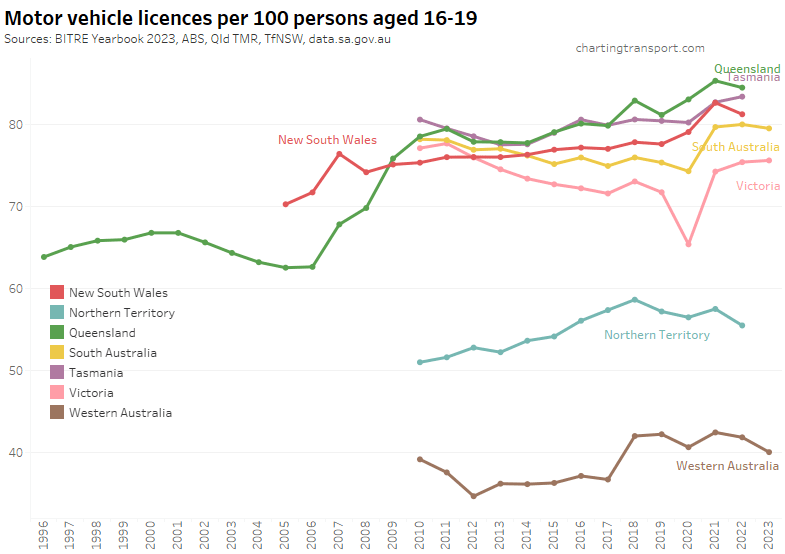

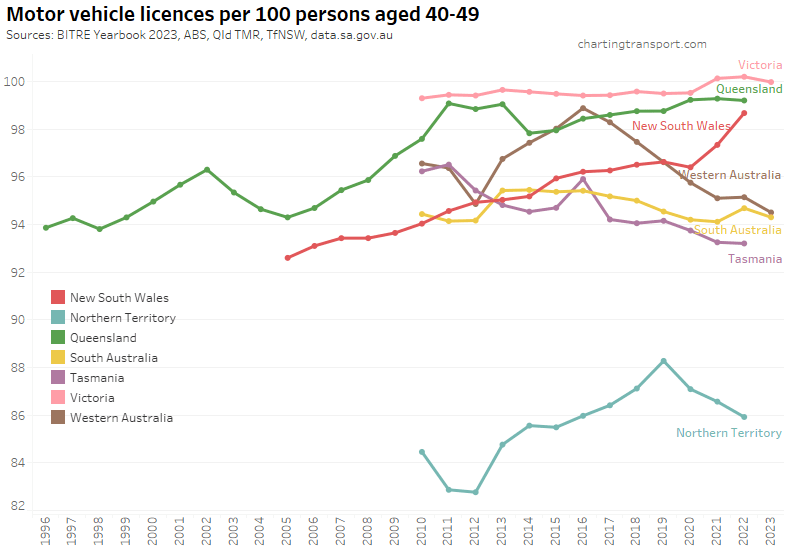

Let’s look at the various age bands across the states:

Victoria saw a sharp decline in Victoria to June 2020, followed by a bounce back to a higher rate in 2021. The pandemic has also been associated with increased rates in South Australia, Tasmania, and New South Wales (although it dropped again in 2022). Western Australia and the Northern Territory have much lower licence rates, likely due to different eligibility ages for learner’s permits.

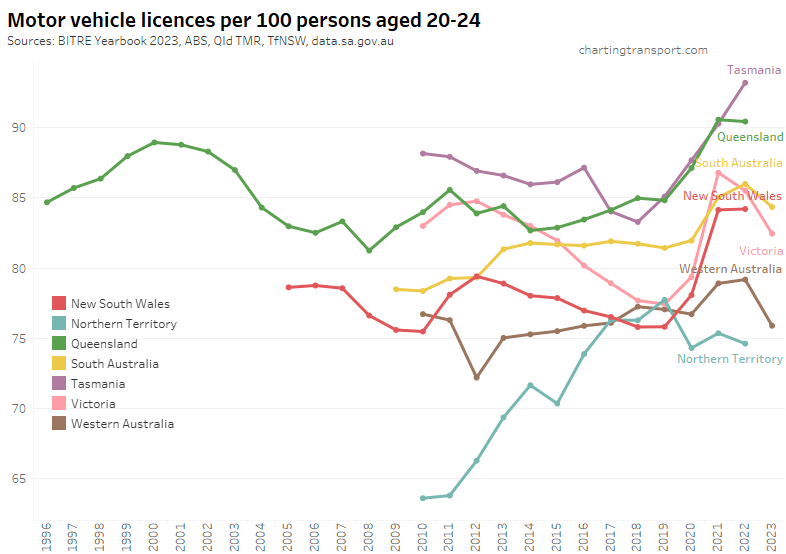

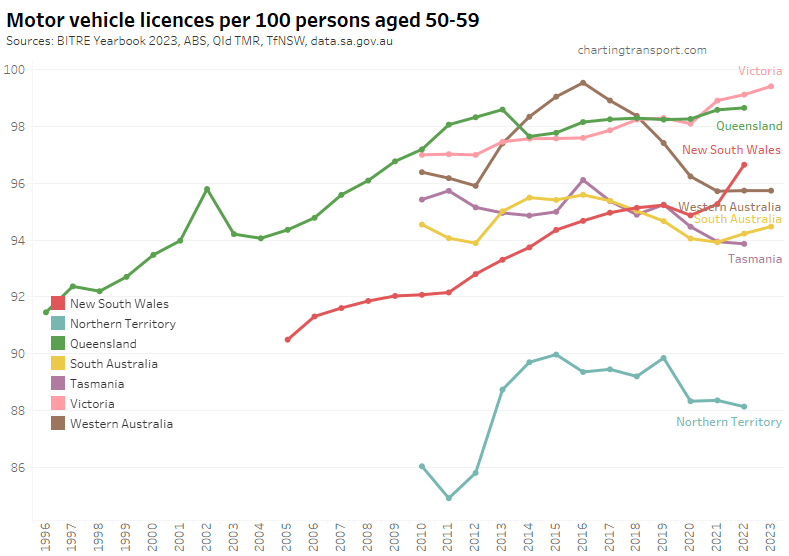

For 20-24 year olds the pandemic caused big increases in the rate of licence ownership in most states, however Victoria, South Australia, and Western Australian appear to have peaked. Licence ownership among 20-24 year olds was still surging in Tasmania up to June 2022.

Similar patterns are evident for 25-29 year olds:

One trend I identified a year ago was that the increasing rate of licence ownership seemed to largely reflect a decline in the population in these age bands during the pandemic period when temporary migrants were told to go home, and immigration almost ground to a halt. Most of the population decline was those without a licence, while the number of licence holders remained fairly steady.

New South Wales appears to follow this pattern, although there was strong growth in licence holders in 2021 and 2022 for teenagers.

Victoria saw a decline in licence holders in 2020 (likely teenagers unable to get a learner’s permit due to lockdowns), but the number of teenage licence holders has since grown. While for those in their 20s, the increase in the licence ownership rate is mostly explained by a loss of population without a licence:

Queensland has experienced strong growth in licence holders at the same time as a decline in population aged 20-29 in 2022. This might be the product of departing temporary immigrants partly offset by interstate migration to Queensland.

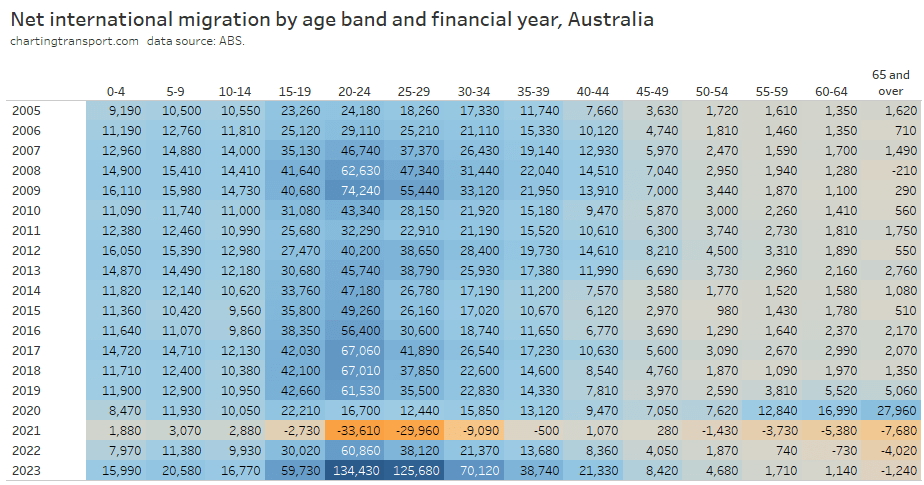

To illustrate how important migration is to the composition of young adults living in Australia, here’s a look at the age profile of net international immigration over time for Australia:

For almost all years, the age band 20-24 has had the largest net intake of migrants. This age band also saw declining rates of driver’s licence ownership – until the pandemic, when there was a big exodus and at the same time a significant increase in the drivers licence ownership rate. The younger adult age bands have seen a surge in 2022-23, and in the three states with data the licence ownership rates have dropped (as I predicted a year ago).

Curiously as an aside, 2019-20 saw a big increase in older people migrating to Australia (perhaps people who were overseas returning home during the pandemic lock downs). But then big negative numbers were seen in 2020-21, and since then there has continued to be net departures in 65+ age band.

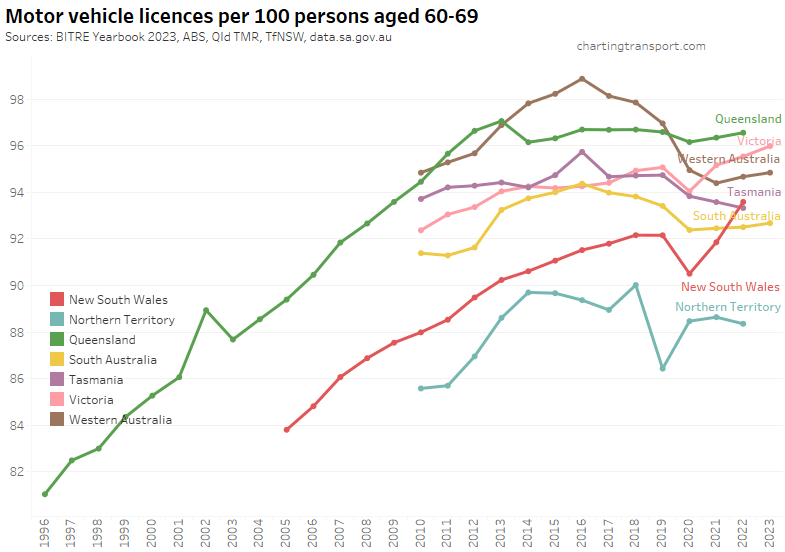

For completeness, here are licence ownership rate charts for other age groups:

There appear to be a few dodgy outlier data points for the Northern Territory (2019) and South Australia (2016).

You might have noticed some upticks for New South Wales in 2022, particularly for those aged over 80. I’m not sure how to explain this. Here’s all the age bands for NSW:

Here’s Victoria, which includes data to 2023:

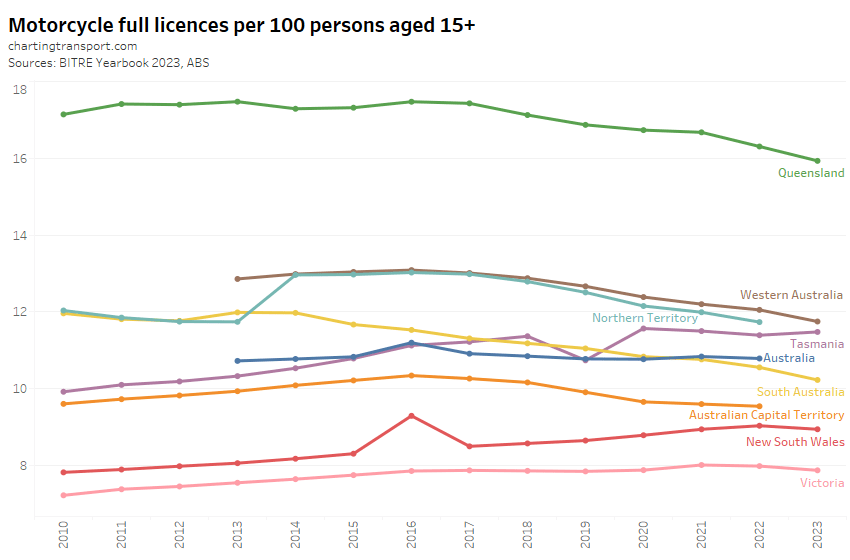

For completeness, here are motor cycle licence ownership rates:

Motorcycle licence ownership per capita has been declining in most states and territories, except Tasmania. I suspect dodgy data for New South Wales 2016, and Tasmania 2019.

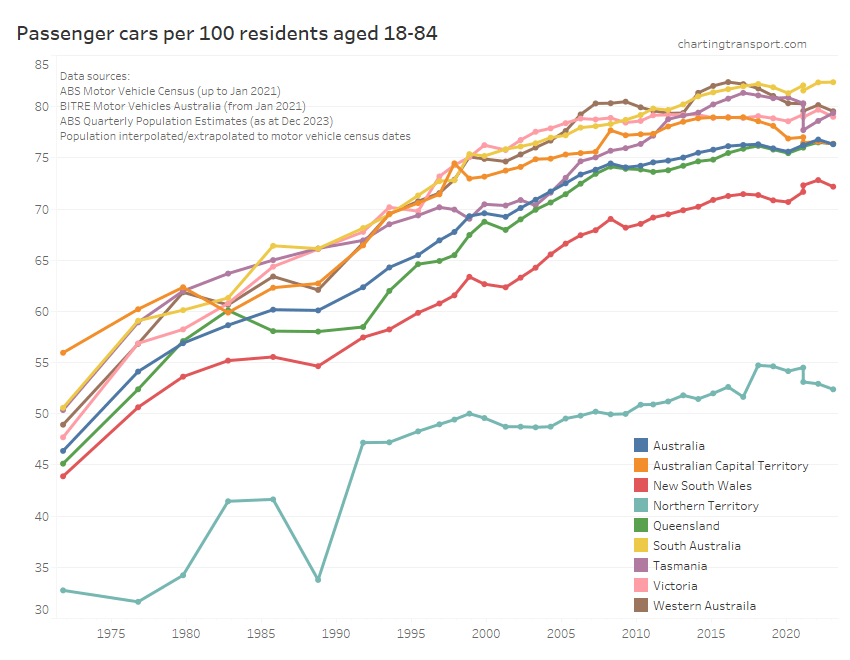

Car ownership

Thankfully BITRE has picked up after the ABS terminated it’s Motor Vehicle Census, and are now producing a new annual report Motor Vehicle Australia. They’ve tried to replicate the ABS methodology, but inevitably have come up with slightly different numbers in different states for different vehicle types for 2021 (particularly Tasmania). So the following chart shows two values for January 2021 – both the ABS and BITRE figures so you can see the reset more clearly. I suggest focus on the gradient of the lines between surveys and try to ignore the step change in 2021.

Let’s zoom in on the top-right of that chart:

All except South Australia, Tasmania, and ACT showed a decline in motor vehicle ownership between January 2022 and January 2023. This might reflect the recent return of “recent immigrants” (as I predicted a year ago).

Tasmania had a large difference in 2021 estimates between ABS and BITRE that seems to be closing so who knows what might be going on there.

Several states appear to have had peaks – Tasmania in 2017, Western Australia in 2016, and ACT in 2017.

Vehicle fuel types

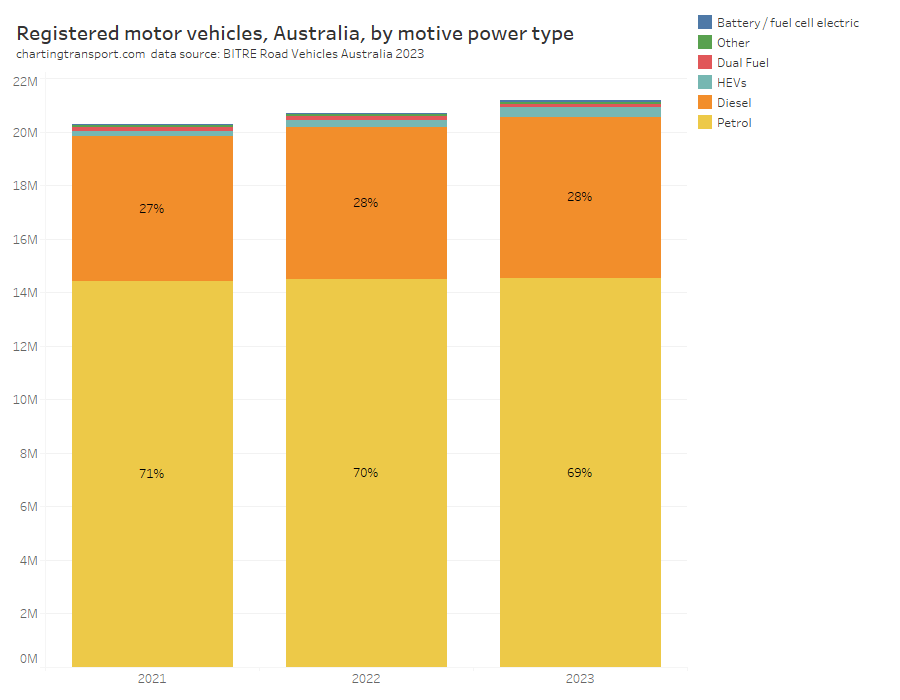

Petrol vehicles still dominate registered vehicles, but are slowly losing share to diesel:

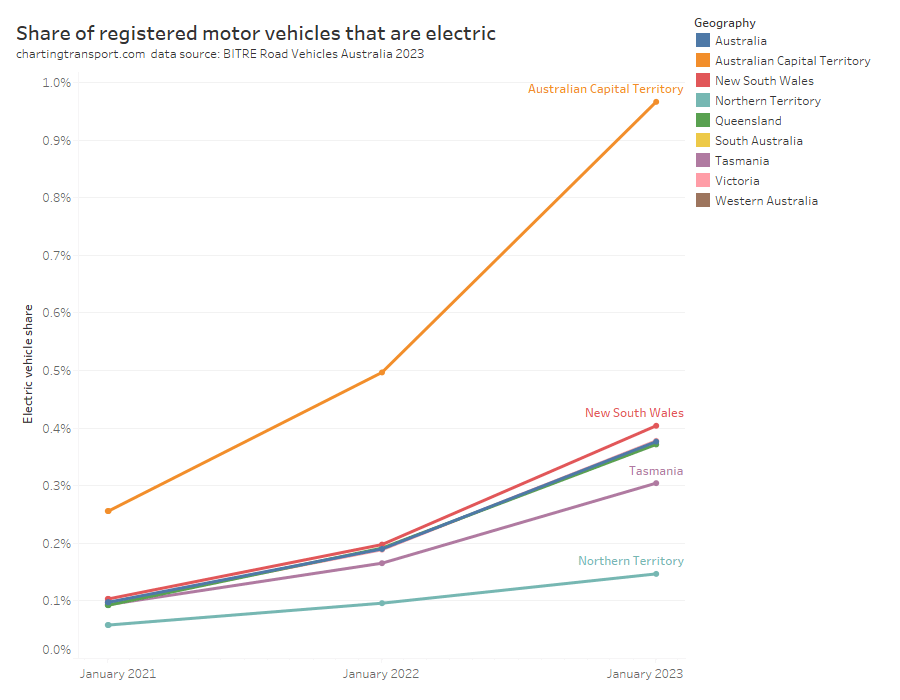

Can you see that growing slither of blue at the top, being electric vehicles? Nor can I, so here’s the share of registered vehicles that are fully electric (battery or fuel cell, but not hybrids):

The almost entirely urban Australian Capital Territory is leading the country in electric vehicle adoption, while the Northern Territory is the laggard.

Motor vehicle sales

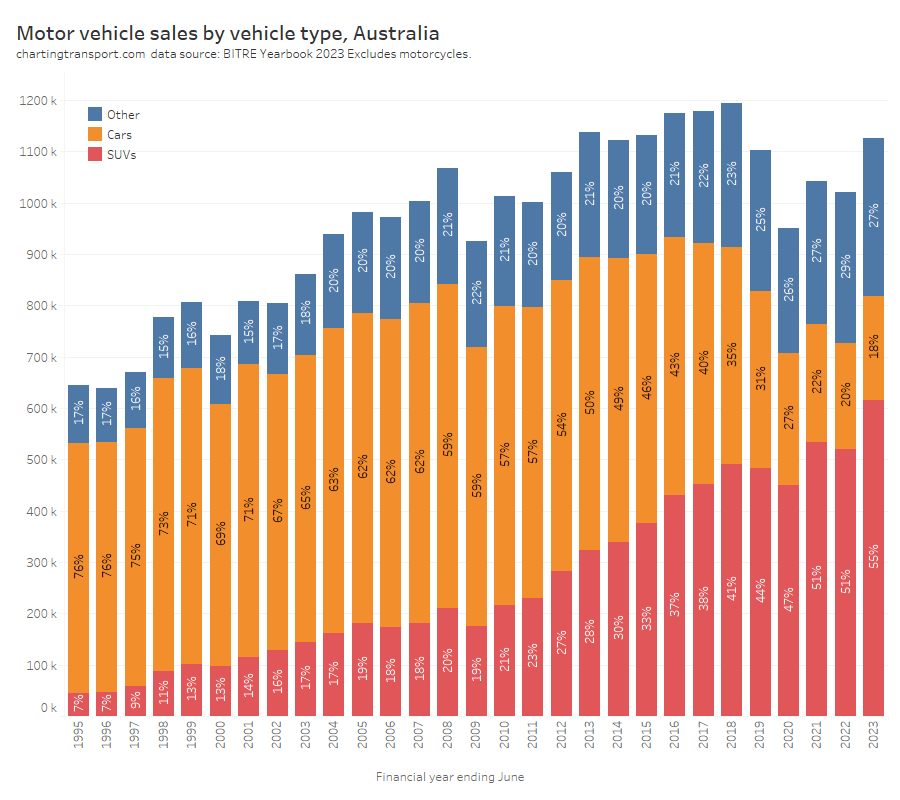

Here are motor vehicle sales by vehicle type:

The trend to larger and heavier vehicles (SUVs) might make it harder to bring down transport emissions (and perhaps reduce road deaths).

Electric vehicle sales are small but currently growing fast in volume and share:

[Updated 7 January 2024:] I’ve included calendar year 2023 sales from FCAI (their 2022 figures were very close to BITRE’s) and calculated the percentage of sales that were battery electric based on FCAI/ABS totals.

Transport Emissions

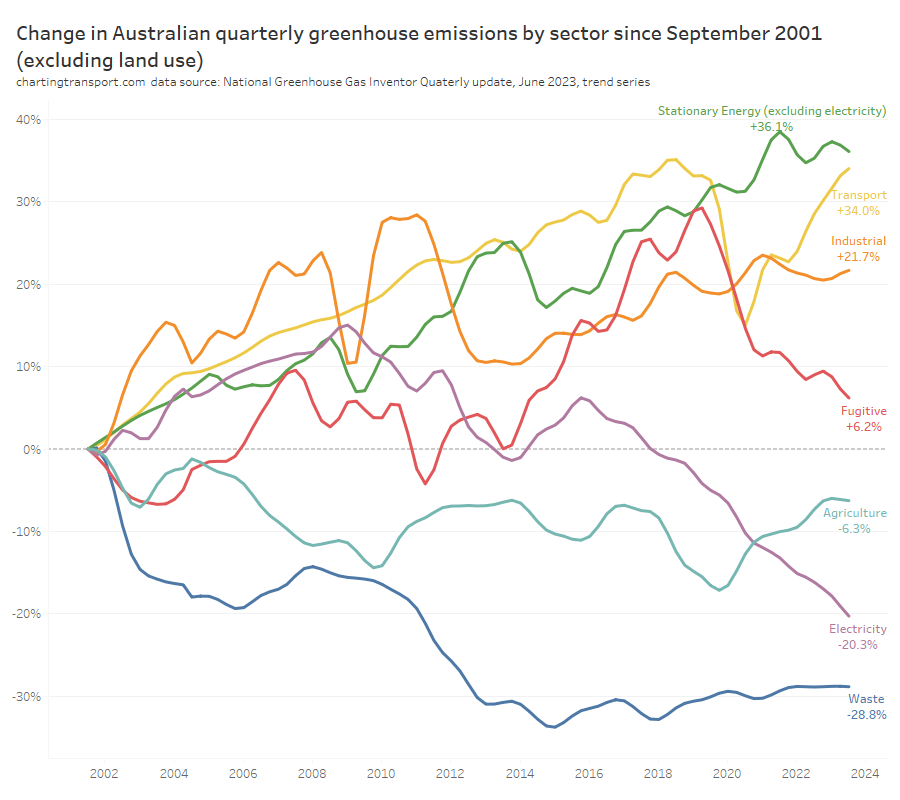

Transport now makes up 19% of Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions (excluding land use), up from 15% in 2001:

You can see that Australia’s total emissions excluding land use have actually increased since 2001. Emissions reductions in the electricity sector have been offset by increases in other sectors, including transport.

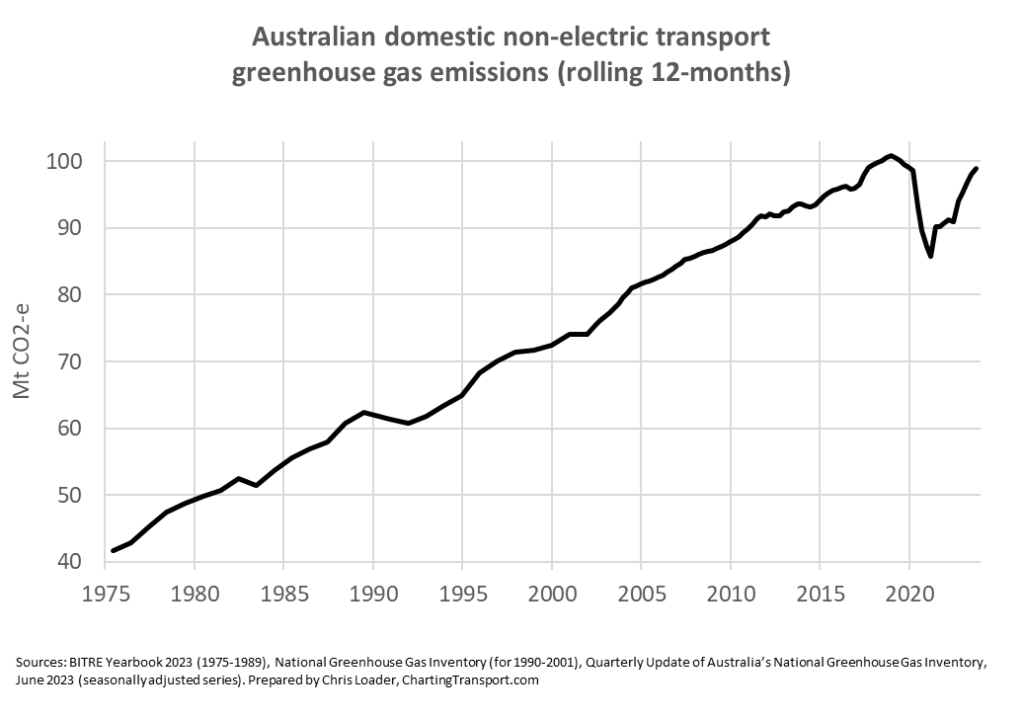

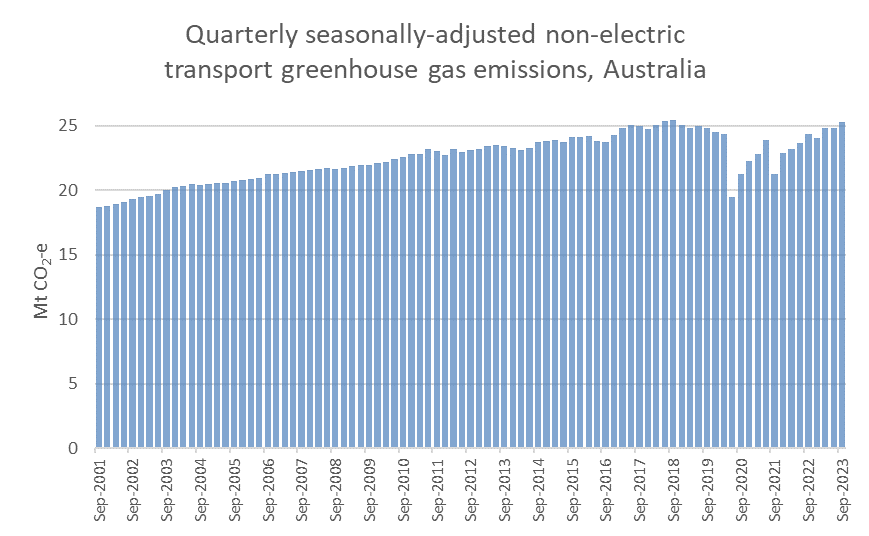

Australia’s transport rolling 12 month emissions dropped significantly with COVID lockdowns, but are bouncing back strongly:

Here are seasonally-adjusted quarterly estimates, showing September 2023 emissions back to 2018 levels:

Transport emissions are around 34% higher in September 2023 than in September 2001, the second highest growth of all sectors since that time:

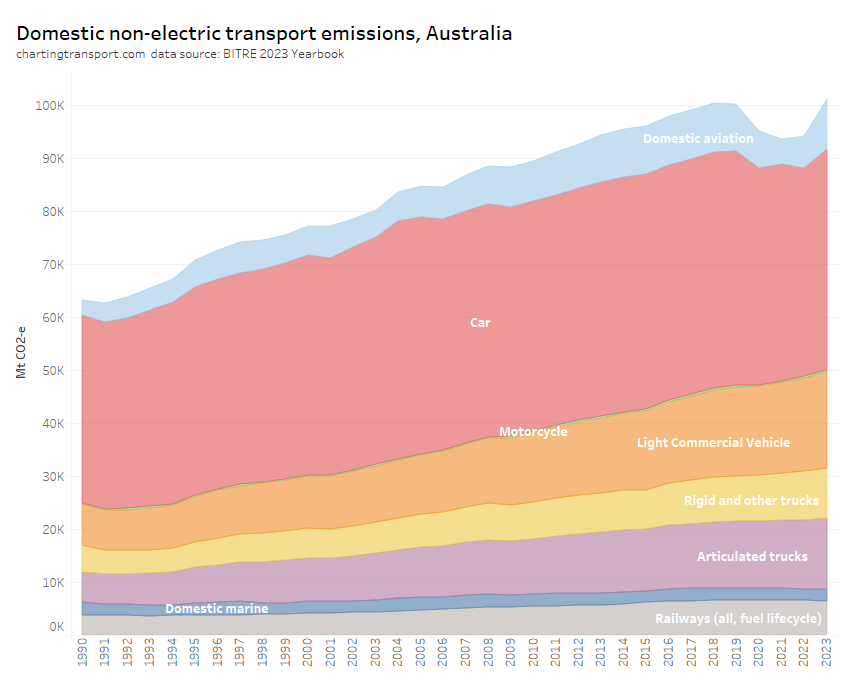

Here are annual Australian transport emissions since 1975:

And in more detail since 1990:

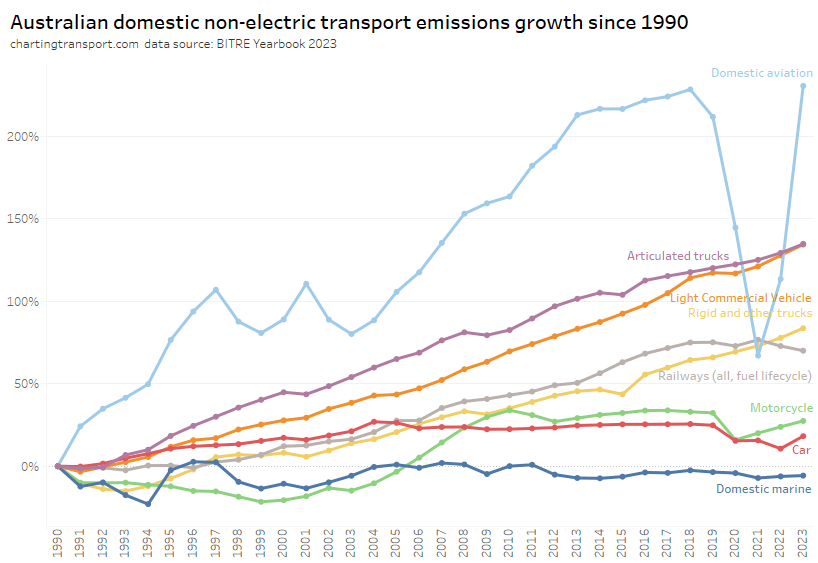

The next chart shows the growth trends by sector since 1990:

Aviation emissions saw the biggest dip during the pandemic but are now back above 2018 levels.

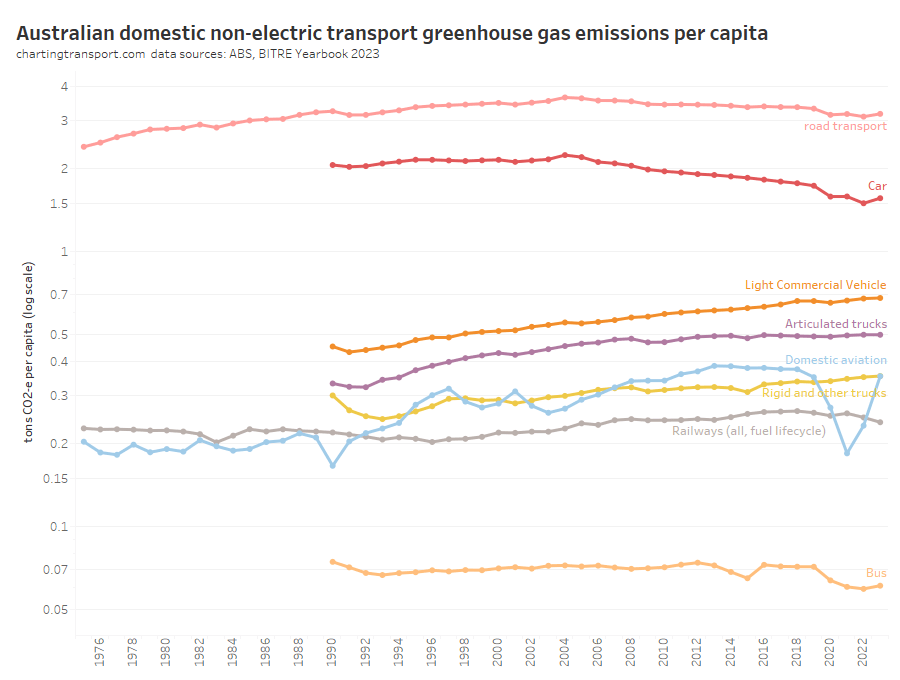

Here are per capita emissions by transport sector (note: log scale used on Y-axis):

Truck and light commercial vehicle emissions per capita have continued to grow while many other modes have been declining, including a trend reduction in car emissions per capita since around 2004.

Next up, emissions intensity (per vehicle kilometre):

I suspect a blip in calculation assumptions in 2015 for bus and trucks.

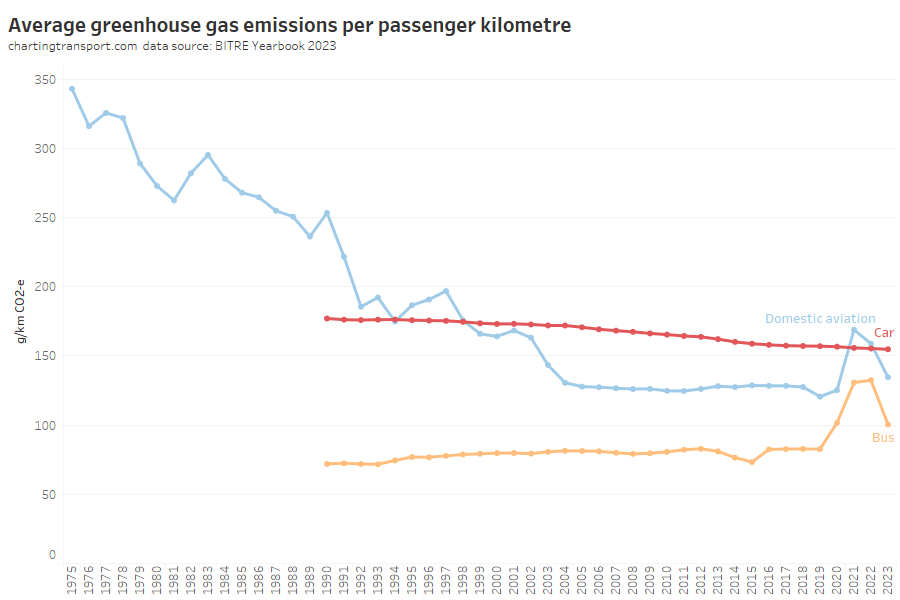

Emissions per passenger kilometre can also be estimated:

Car emissions have continued a slow decline, but bus and aviation emissions per passenger km increased in 2021, presumably as the pandemic reduced average occupancy of these modes.

Aviation was reducing emissions per passenger kilometre strongly until around 2004, but has been relatively flat since, and the 2022-23 value is above 2004 levels. This seems a little odd as newer aircraft are generally more energy efficient.

Transport consumer costs

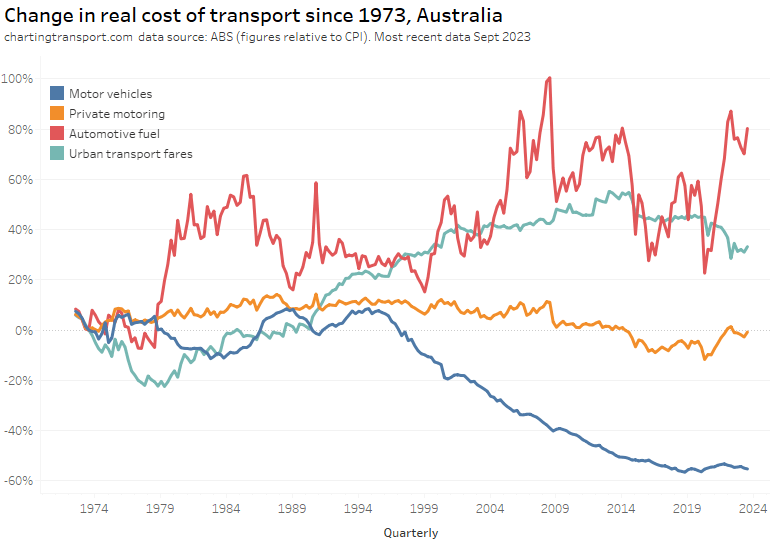

The final category for this post is the real cost of transport from a consumer perspective. Here are headline real costs (relative to CPI) for Australia, using quarterly ABS Consumer Price Index data up to September 2023:

Technical note: Private motoring is a combination of factors, including motor vehicle retail prices and automotive fuel.

The cost of motor vehicles was in decline from around 1995 to 2018 and has been stable or slightly rising since then. Automotive fuel has been volatile, which has contributed to variations in the cost of private motoring.

Urban transport fares (a category which unfortunately blends public transport and taxis/rideshare) have increased faster than CPI since the late 1970s, although they were flat in real terms between 2015 and 2020, then dropped in 2021 and 2022 in real terms – possibly as they had not yet been adjusted to reflect the recent surge in inflation. They picked up slightly in 2023.

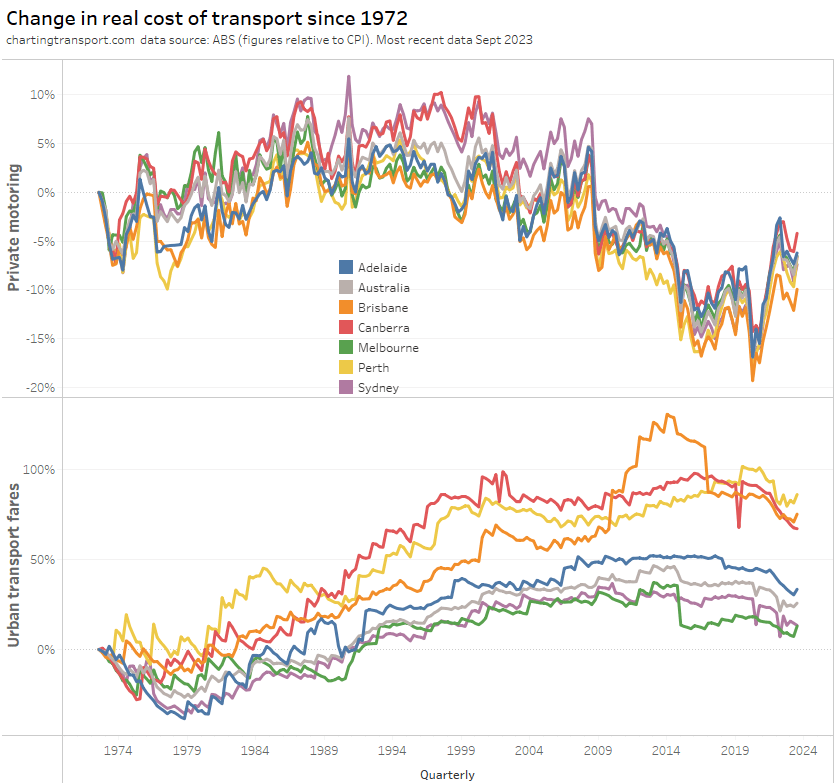

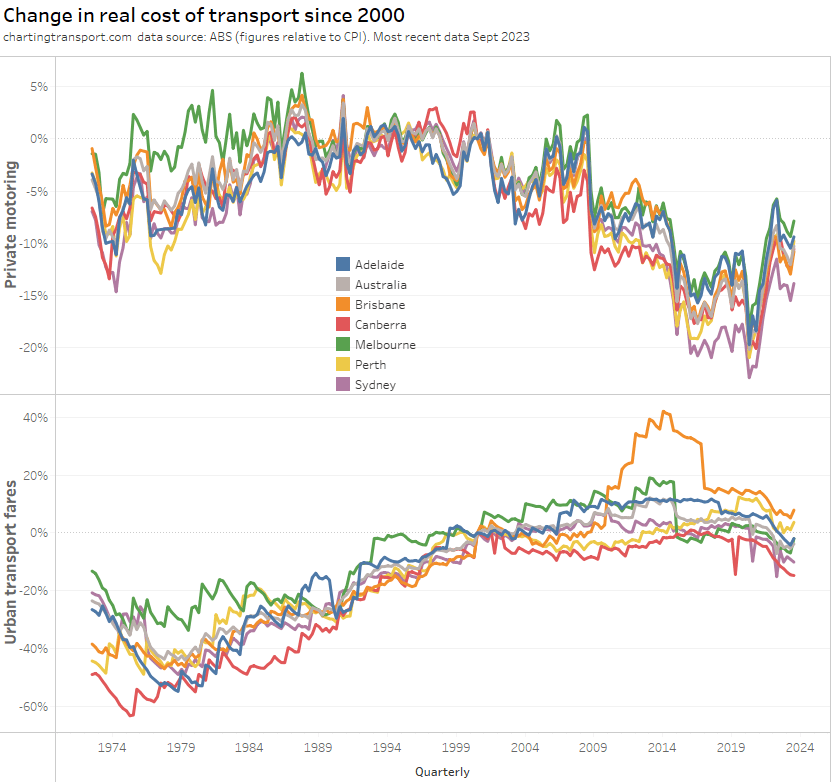

The above chart shows a weighted average of capital cities, which washes out patterns in individual cities. Here’s a breakdown of the change in real cost of private motoring and urban transport fares since 1972 by city (note different Y-axis scales):

Technical note: The occasional dips in urban transport fares value are likely related to periods of free travel – eg May 2019 in Canberra.

The cost of private motoring moves much same across the cities.

Urban transport fares have grown the most in Brisbane, Perth, and Canberra – relative to 1972. However all cities have shown a drop in the real cost of urban transport fares in June 2022 – as discussed above.

If you choose a different base year you get a different chart:

What’s most relevant is the relative change between years – e.g. you can see Brisbane’s experiment with high urban transport fare growth between 2009 and 2017 in both charts.

Melbourne recorded a sharp drop in urban transport fares in 2015, which coincided with the capping of zone 1+2 fares at zone 1 prices.

And that’s a wrap on Australian transport trends. Hopefully you’ve found this useful and/or interesting.

Posted by chrisloader

Posted by chrisloader