[Updated 1 December 2017 with reissued Place of Work data]

The ABS has now released all census data for the 2016 journey to work. This post takes a city-level view of mode share trends. It has been expanded and updated from a first edition that only looked at place of work data.

My preferred measure of mode share is by place of enumeration – ie how did you travel to work based on where you were on census night (see appendix for discussion on other measures).

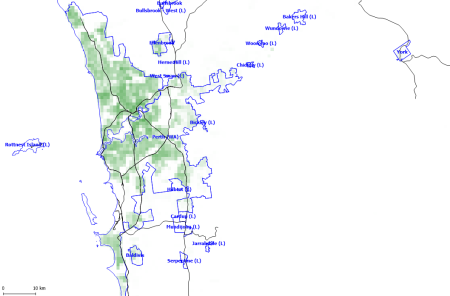

I’m using Greater Capital City Statistical Areas (GCCSA) geography for 2011 and 2016 and Statistical Divisions for earlier years. For Perth, Melbourne, Adelaide, Brisbane and Hobart the GCCSAs are larger than the Statistical Divisions used for earlier years, but then those cities have also grown over time. See appendix 1 for more discussion.

Some of my data goes back to 1976 – I’ll show as much history as I have for each mode/modal combination.

Public transport mode share

Sydney continues to have the largest public transport mode share, and the largest shift of the big cities. Melbourne also saw significant positive mode shift, but Perth and particularly Brisbane had mode shift away from public transport.

There’s so much to unpack behind these trends, particularly around the changing distribution of jobs in cities that I’m going to save that lengthy discussion for another blog post.

But what about the…

Massive mode shift to “public transport” in Darwin?!?

[this section updated 26 Oct 2017]

Yes, I have triple-checked I downloaded the right data. “Public transport” mode share increased from 4.3% to 10.9%. The number of people reporting bus-only journeys went from 1648 in 2011 to 5661 in 2016, which is growth of 244%. There has also been a spike in the total number of journeys to work in 2011, 30% higher than in 2011, while population growth was 13%.

Initially I thought this might have been a data error, but I’ve since learnt that there is a large LNG gas project just outside Darwin, and up to 180 privately operated buses are being used to transport up to 4700 workers to the site. This massive commuter task is swamping the usage of public buses.

Here’s the percentage growth in selected journey types between 2011 and 2016:

Bus + car as driver grew from 74 to 866 journeys, which reflects the establishment of park and ride sites around Darwin for the special commuter buses. Bus only journeys increased from 1953 to 5744. So it looks like most workers are getting the bus from home and/or forgot to mention the car part of their journey (in previous censuses I’ve seen many people living kilometres from a train station saying they got to work by train and walking only).

So this new project has swamped organic trends, although it is quite plausible that some people have shifted from cycling/walking to local jobs to using buses to commute to the LNG project (which is outside urban Darwin). When I look at workplaces within the Darwin Significant Urban Area (2011 boundary), public transport mode share is 6.0%, in 2016, still an increase from 4.4% in 2011. More on that in a future post.

Train

Sydney saw the fastest train mode share growth, followed by Melbourne, while Brisbane and Perth went backwards.

Bus

Darwin just overtook Sydney for top spot thanks to the LNG project. Otherwise only Sydney, Canberra and Melbourne saw growth in bus mode share. Melbourne’s figure remains very low, however it is important to keep in mind that trams provide most of the on-street inner suburban radial public transport function in Melbourne.

Train and bus

Sydney comes out on top, with a large increase in 2016 (although much of this is still concentrated around Bondi where there are high bus frequencies and no fare penalties for transfers – more on that in an upcoming post). Melbourne is seeing substantial growth (perhaps due to improvements in modal coordination), while Perth, Adelaide and Brisbane had declines in terms of mode share (Brisbane and Adelaide were also declines on raw counts, not just mode share). I’m sure some people will want to comment about degrees of modal integration in different cities.

Train and bicycle

Some cities are also trying to promote the bicycle and train combination as an efficient way to get around (they are the fastest motorised and (mostly)non-motorised surface modes because they can generally sail past congested traffic). The mode shares are still tiny however:

Sydney and Melbourne are growing but the other cities are in decline in terms of mode share.

As this modal combination is coming off an almost zero base, it’s also probably worth looking at the raw counts:

The downturns in Brisbane and Perth are not huge in raw numbers, and probably reflect the general mode shift away from public transport (which is probably more to do with changing job distributions than bicycle facilities at train stations).

Cycling

I have a longer time-series of bicycle-only mode share, compared to “involving bicycle”, so two charts here:

Observations:

- Darwin lost top placing for cycling to work with a large decline in mode share (refer discussion above about the massive shift to bus).

- Canberra took the lead with more strong growth.

- Melbourne increased slightly between 2011 and 2016 (note: rain was forecast on census day which may have suppressed growth, more on that in a moment).

- Hobart had a big increase in 2016, following rain in 2011.

- Sydney remains at the bottom of the pack and declined in 2016.

Walking and cycling mode share is likely to be impacted by weather. Here’s a summary of recent census weather conditions for most cities (note: Canberra minimums were -3 in 2001, -7 in 2006, 0 in 2011 and -1 in 2016):

Perth had rain on all of the last four census days, while Adelaide had significant rain only in 2001 and 2011 (and indeed 2006 shows up with higher active transport mode share). Hobart had significant rain in 2011, which appears to have suppressed active transport mode share that year.

But perhaps equally important is the forecast weather as that could set people’s plans the night before. Here was the forecast for the 2016 census day, from the BOM website the night before:

Note that it didn’t end up raining in Melbourne, Adelaide, or Hobart.

The census is conducted in winter – which is the best time to cycle in Darwin (dry season) and not a great time to cycle in other cities. However the icy weather in Canberra clearly hasn’t stopped it getting the highest and fastest growing cycling mode share of all cities!

Indeed here is a chart from VicRoads showing the seasonality of cycling in Melbourne at their bicycle counters:

And in case you are interested, here are the (small) mode shares of journeys involving bicycle and some other modes (other than walking):

Walking only

Canberra was the only city to have a big increase, while there were declines in Darwin, Perth, Adelaide, Brisbane, and Sydney.

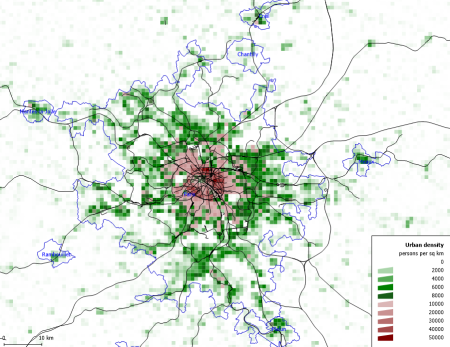

The smaller cities had the highest walking share, perhaps as people are – on average – closer to their workplace, followed by Sydney – the densest city. But city size doesn’t seem to explain cycling mode shares.

Car

The following chart shows the proportion of journeys to work made by car only (either as driver or passenger):

Sydney has the lowest car only mode share and it declined again in 2016. It was followed by Melbourne in 2016. Brisbane and Perth had large increases in car mode share in 2016 (in line with the PT decline mentioned above). Darwin also shows a big shift away from the car to public transport (although the total number of car trips still increased by 24%). Adelaide hit top spot, followed by Hobart and Perth.

Here is car as driver only:

And here is car as passenger only:

Car as passenger declined in all cities again in 2016, but was more common in the smaller cities, and least common in the bigger cities. I’m not sure why car as passenger declines paused for Perth and Sydney in 2006.

We can calculate an implied notional journey to work car occupancy by comparing car driver only and car passenger only journeys. This is not actual car occupancy, because it excludes people not travelling to work and excludes journeys that involved cars and other modes. However it does provide an indication of trends in car pooling for journeys to work.

There were further significant decreases in car commuter occupancy, in line with increasing car ownership and affordability.

Private transport

Here is a chart summing all modal combinations involving cars (driver or passenger), motorcycle/scooter, taxis, and trucks, but excluding any journeys that also include public transport.

The trends mirror what we have seen above, and are very similar to car-only travel.

Overall mode split

Here’s an overall split of journeys to work by “main mode” (click to enlarge):

Note: the 2001 data includes estimated splits of aggregated modes based on 2006 data.

I assigned a ‘main mode’ based on a hierarchy as follows:

- Any journey involving train is counted with the main mode as train

- Any other journey involving bus is counted with the main mode as bus

- Any other journey involving tram and/or ferry is counted as “tram/ferry”

- Any other journey involving car as driver, truck or motorbike/scooter is counted as “vehicle driver”

- Any other journey involving car as passenger or taxi is counted as “vehicle passenger”

- Any other journey involving walking or cycling only as “active”

How different are “place of work” and “place of enumeration” mode shares?

[this section updated 1 December 2017 with re-issued Place of Work data. See new Appendix 3 below for analysis of the changes]

The first edition of this post reported only “place of work” data, as place of enumeration data wasn’t released until 11 November 2017. This second edition now focuses on place of enumeration – where people were on census night.

The differences are not huge, as most people who live in a city also work in that city, but there are still a number of people who leave or enter cities’ statistical boundaries to go to work. Here’s an animation showing the main mode split by place of work and enumeration so you can compare the differences (you’ll need to click to enlarge). The animation dwells longer on place of work data.

Public + active transport main mode shares are generally higher for larger cities with place of work data, and smaller for smaller cities.

Here’s a closer look at the 2016 public transport mode shares by the two measures:

See also a detailed comparison in Appendix 1 below for 2011 Melbourne data.

I’d like to acknowledge Dr John Stone for assistance with historical journey to work data.

Appendix 1 – How to measure journey to work mode share

Firstly, I exclude people who did not work, worked at home, or did not state how they worked. The first two categories generate no transport activity, and if the actual results for “not stated” were biased in any way we would have no way of knowing how.

I prefer to use “place of enumeration” data (ie where people were on census night). “Place of usual residence” data is also available, but is unfortunately contaminated by people who were away from home on census day. The other data source is “Place of work”.

Some people might prefer to measure mode shares on Urban Centres which excludes rural areas within the larger blobs that are Greater Capital City Statistical Areas and Statistical Divisions (use this ABS map page to compare boundaries). However, “place of work” data is not readily available for that geography, and this method also excludes satellite urban centres that might be detached from the main urban centre, but are very much part of the economic unit of the city.

Another option is “Significant Urban Area”, which includes more fringe areas, and some more satellite towns, and in Canberra’s case crosses the NSW border to capture Queanbeyan.

What difference does it make?

Here’s a comparison of public transport mode shares for the different methods for 2011.

If you look closely, you’ll notice:

- The more than you remove non-urban areas, the higher your public transport mode share, which makes sense, as those non-urban areas are mostly not served by public transport.

- Place of usual residence tends to increase public transport mode shares for smaller cities (people probably visiting larger cities) and depresses public transport mode share in larger cities (people visiting smaller cities and towns).

- Place of work is only readily available for Greater Capital City Statistical Areas. For the bigger cities it tends to inflate PT mode share where people might be using good inter-urban public transport options, or driving to good public transport options on the edges of cities (eg trains). However it has the opposite impact in Darwin and Canberra, where driving into the city is probably easier.

But I think the main point is that for any time series trend analysis you should use the same measure if possible.

If you want to compare the two, I’ve created a Tableau Public visualisation that has a large number of mode shares by both place of work and place of enumeration.

Appendix 2 – Estimating pre-2006 mode shares from aggregated data

For 2006 onwards, ABS TableBuilder provides counts for every possible combination of up to three modes (other than walking, which is assumed to be part of every journey). For example, in Melbourne in 2006, 36 people went to work by taxi, car as driver, and car as passenger (or so they said!). Unfortunately for years before 2006 data is not readily available with a full breakdown.

The 2001 data includes only aggregated counts for the following categories:

- train and other (excluding bus)

- bus and other (excluding train)

- other two modes (no train or bus)

- train and two other modes

- bus and two other modes (excluding train)

- three other modes (no train or bus)

Together these accounted for 3.7% of journeys in Melbourne and 4.5% of journeys in Sydney.

However all but two of those aggregate categories definitely involve train and/or bus, so can be included in public transport mode share calculations.

Journeys in the aggregate categories “Other two modes” and “Other three modes” might involve tram and/or ferry trips (if such modes exist in a city), but we don’t know for sure.

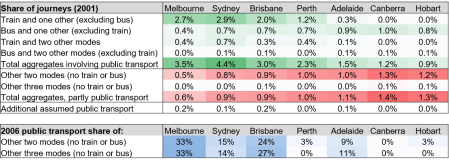

I’ve used the complete modal data for 2006 to calculate the percentage of 2006 journeys that fit into these two categories that are by public transport. I’ve then assumed these same percentage apply in 2001 to estimate total public transport mode shares for 2001 (for want of a better method).

Here are the 2001 relevant stats for each city:

(note: totals do not add perfectly due to rounding)

The estimates add up to 0.2% to the total public transport mode shares in cities with significant modes beyond train and bus (namely ferry and tram in Sydney, tram in Melbourne, ferry in Brisbane, tram and Adelaide). This almost entirely comes from “other two modes” category while “other three modes” is tiny. For these categories, almost no journeys in Perth, Canberra and Hobart actually involved a public transport mode.

In the past I have knowingly ignored public transport journeys that might be part of these categories, which almost certainly means public transport mode share is underestimated (I suspect most other analysts have too). By including some assumed public transport journeys my estimate should be closer to the true value, which I think is better than an underestimate.

But are these reasonable estimates? Are the 2001 modal breakdowns for these categories likely to be the same as 2006? Maybe not exactly, but because we are multiplying small numbers by small numbers, the impact of slightly inaccurate estimates is unlikely to shift the total by more than 0.1%. I tested the methodology between 2006 and 2011 results (eg using 2011 full breakdown against created 2006 aggregate categories and vice versa) and the estimated total mode shares were almost always exactly the same as the perfectly calculated shares (at worst there was a difference of 0.1% when rounding to one decimal place).

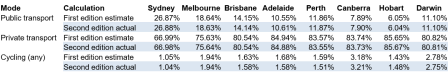

In the first edition of this post I had to estimate 2016 place of work mode shares in a similar way for public and private transport, but I wasn’t confident enough to estimate mode share of journeys involving cycling.

I now have the final data and I promised to see how I went, so here’s a comparison:

If you round to one decimal place, the estimates were no different for public and private transport and out by up to 0.1% for cycling (which is relatively significant for the small cycling mode shares).

I’ve applied a similar approach to estimate several other mode share types, and these are marked on charts.

Appendix 3 – How different is the re-issued place of work data?

In December 2017, ABS re-issued Place of Work data due to data quality issues. This is how they described it:

**The place of work data for the 2016 Census has been temporarily removed from the ABS website so an issue can be corrected. There was a discrepancy in the process used to transform detailed workplace location information into data suitable for output. The ABS will release the updated information in TableBuilder on December 2. The Working Population Profiles will be updated on December 13.**

I have loaded the new data, and here are differences in public transport and private transport mode shares for capital cities:

You can see differences of up to 0.3% (Melbourne PT mode share), but mostly quite small.

Posted by chrisloader

Posted by chrisloader