Sydney’s public transport total patronage in March 2023 was at 79.5% of March 2019 patronage, but then April 2023 total patronage was 73.1% of April 2019 patronage. Does that mean there was a 6.4% decline in the rate of public transport use in April 2023? Actually, no, not at all.

The most common, simple, and obvious way to report public transport patronage is monthly totals. Plenty of agencies do this, but I’m here to argue that invites bad analysis and false conclusions. We can and need to do better.

Let me explain…

Not all days are the same

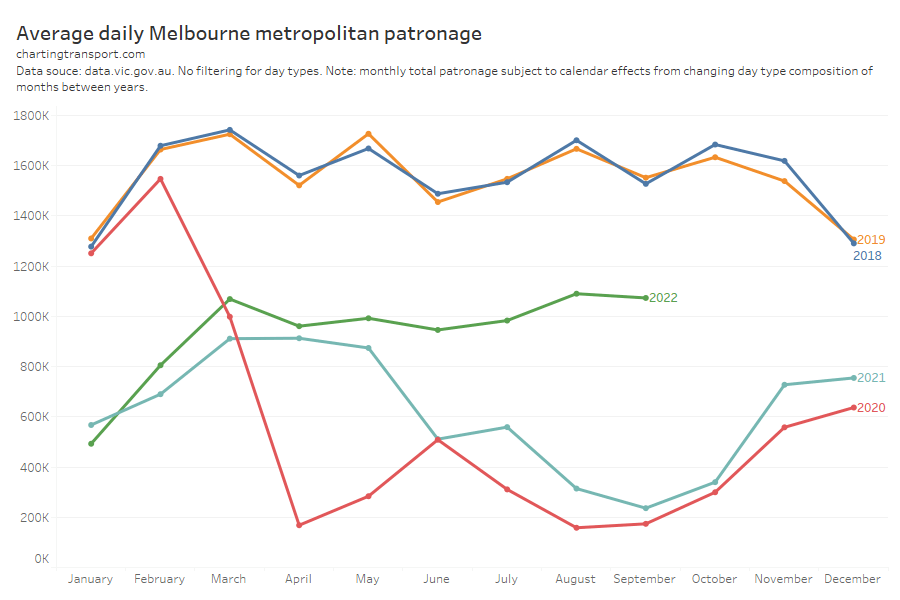

This is stating the obvious, but patronage generally varies by day of the week, and also between school and non-school weekdays. Here’s how it looks for Melbourne 2019 (thanks to newly published data):

The variations across Monday to Friday have increased even more post the pandemic, but that’s another story.

Not all months are the same

Obviously months are not all the same length. A month with 31 days is generally likely to have higher patronage than a month with 28 or 30 days.

Also, most months have a number of days that is not a multiple of 7 – which means that any month is going have a different mix of days of the week in any year (although three-quarters of Februarys are an exception). And we know patronage varies by individual day of the week.

Furthermore, school holidays and public holidays don’t always fall in the same months each year. In particular, Easter is sometimes in March and sometimes in April, and many jurisdictions shift school holidays to line up with Easter in each year. The end result is that the composition of each month can vary considerably between years, both in terms of days of the week and day types.

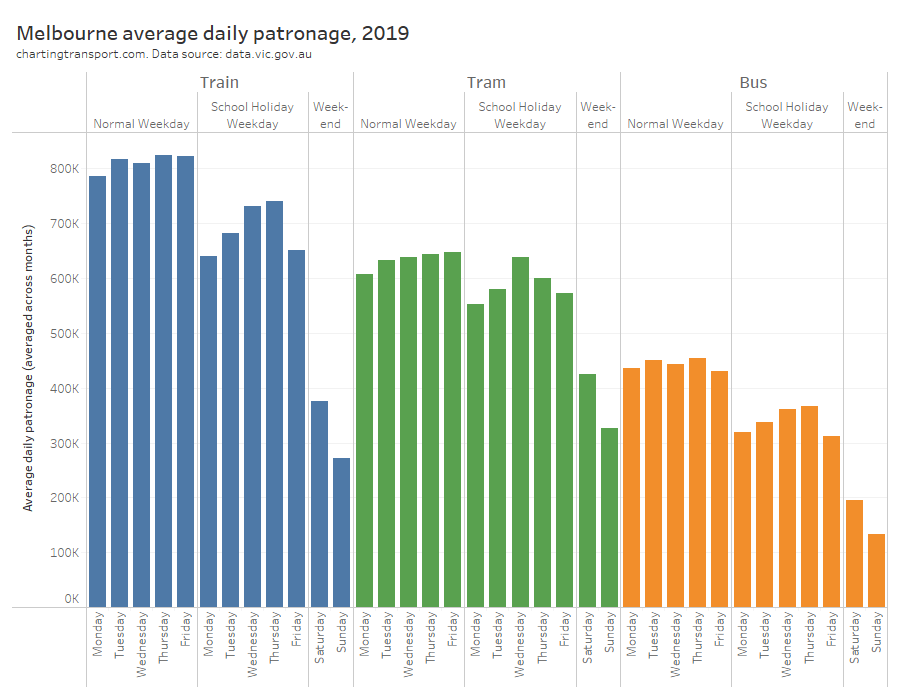

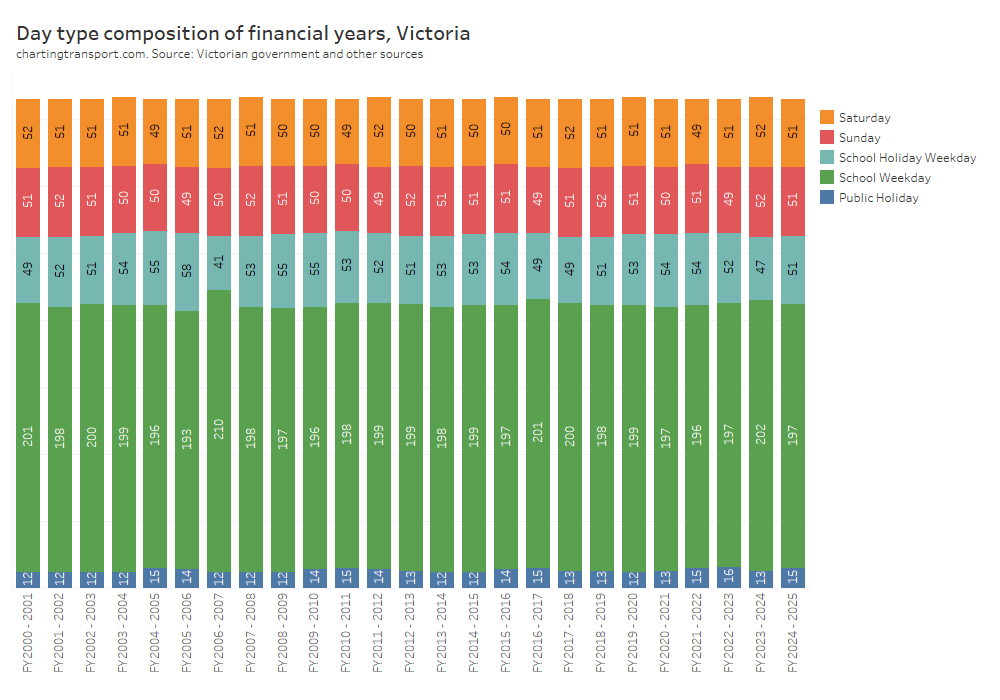

Here’s the day type make up of each month for Victoria for 2000 to 2025:

Some months are pretty consistent – May generally has 21 to 23 school weekdays. But other months vary wildly. March can have anywhere between 8 and 17 school weekdays and anywhere between 1 and 5 public holidays (counting all days of the Easter long weekend as public holidays). There are also big fluctuations in June and July, with school holidays mostly falling in July but sometimes partly or fully in June. And any given month might have 4 or 5 Saturdays and 4 or 5 Sundays (or maybe even 3 if one of them is a public holiday).

In March 2006, Victorian autumn school holidays were in March (when Melbourne hosted the Commonwealth Games) instead of the normal April, and the winter school holidays were entirely in June (normally mostly in July). This will happen again in 2026 when Victoria again hosts the Commonwealth Games.

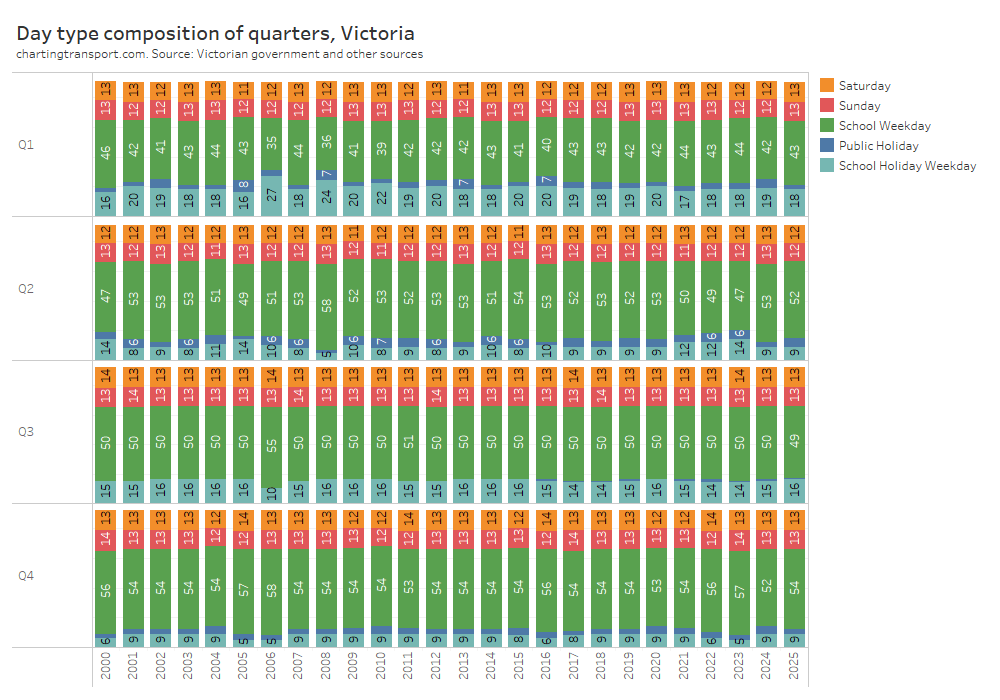

Not all quarters are the same

If months are quite variable in composition, does aggregating to quarters reduce the issues?

In Victoria (and most Australian states), school holidays generally straddle or fall very close to the start/end of quarters. This means there is a fair amount of variability in the day type makeup of most quarters:

In Victoria, quarter 1 can have anywhere between 35 and 44 school days, and between 3 and 7 public holidays. You might also notice that a new Q3 public holiday was introduced in 2016 (Grand Final Eve in late September), and then there was a one-off extra public holiday for the Queen’s death in 2022. The number of public holidays also increases when Christmas Day falls on a Saturday or Sunday.

If you want to understand underling patronage trends, you don’t want to be led astray by these sorts of changes. Quarters are no better than months for analysing total public transport patronage.

Not all financial years are the same either

Another very common way to report patronage data – especially in annual reports – is by financial years (July – June) but they aren’t all that consistent over time either, given that school holidays can slide between June and July, like has happened in Victoria:

Hopefully you’ve got the idea that it isn’t a great idea to analyse total monthly, quarterly, or even financial year patronage if you want to assess trends over time. Yet that’s exactly the most common data you are likely to find.

Calendar years are slightly better for day type composition consistency, but in Victoria calendar years can vary between 50 and 54 school holiday weekdays. And of course every fourth year is one day longer than the others.

A better way: average daily patronage by day of the week and day type

Victoria is now publishing average daily patronage by day of the week and day type (school or non-school weekday) for each month (excluding public holidays).

This means it is possible to compile average school week patronage (being the sum of average daily Sunday, school Monday, school Tuesday, school Wednesday, school Thursday, school Friday, and Saturday patronage). An average school week patronage figure is readily calculable for all months except January (because they have few school days and variable start dates between schools make it a bit messy).

An average school week figure can be calculated regardless of shifting dates of school holidays, public holidays and the general day of the week composition of any month across years. And analysts don’t need to worry about having their own calendar of school and public holidays.

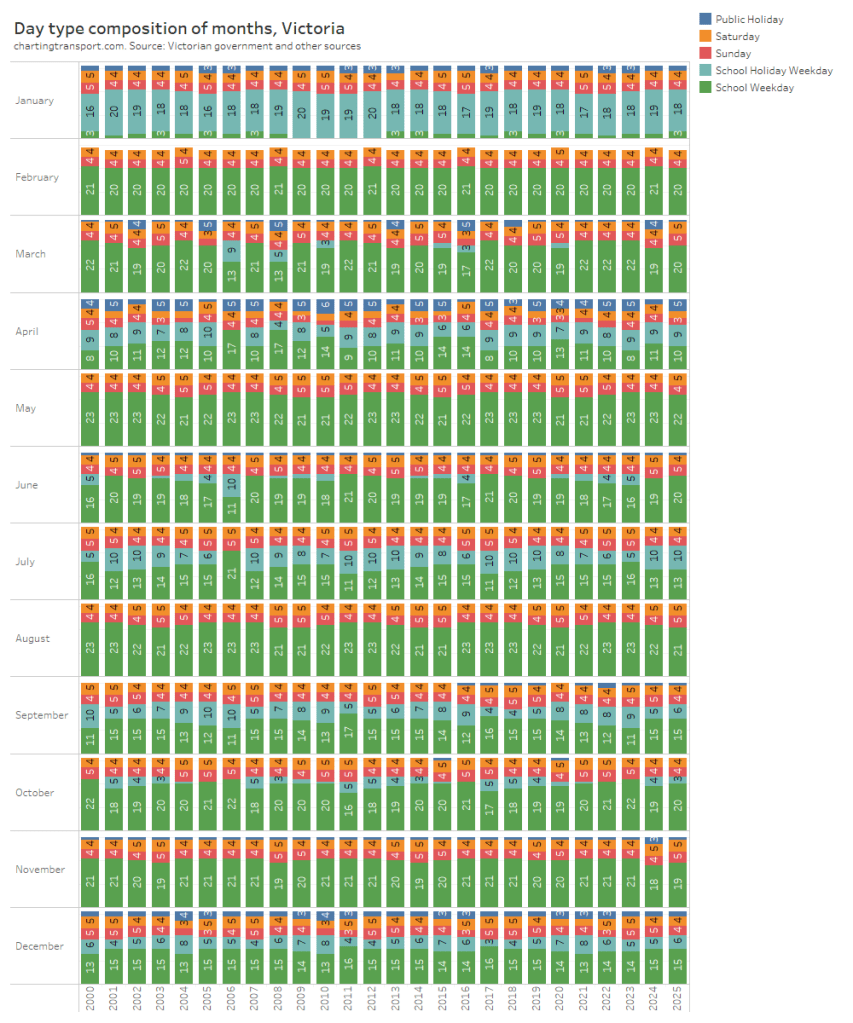

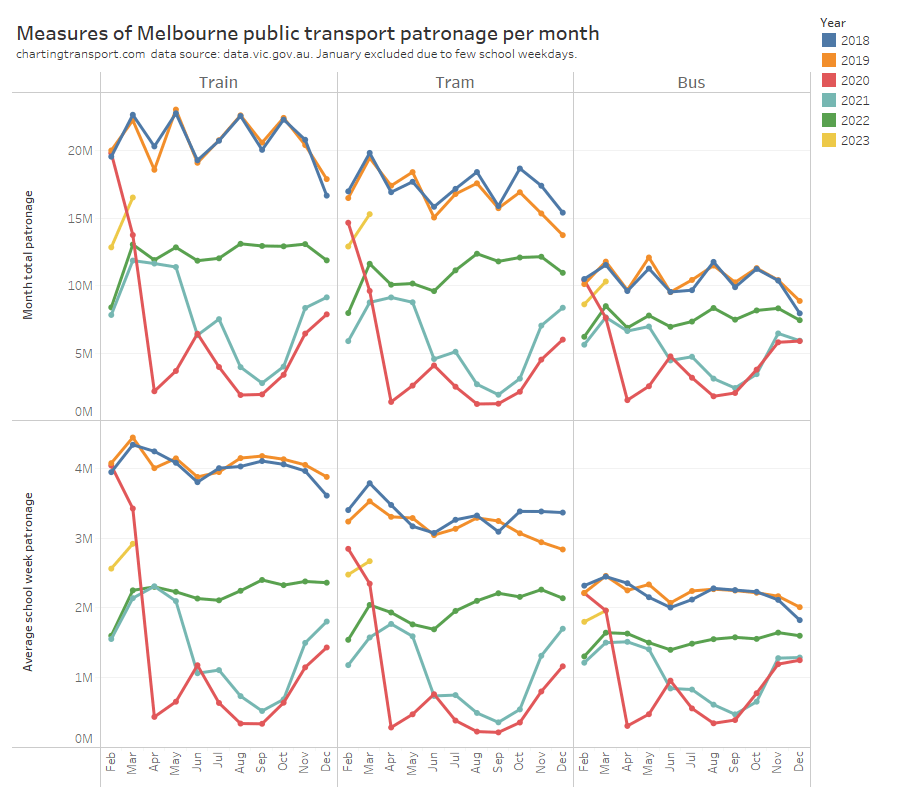

How much cleaner is average school week patronage? Victoria also publishes monthly totals, which makes it possible to compare to average school week figures, as per the following chart:

Note: This time period of course includes the COVID pandemic including lockdowns which is interesting in itself, but for the point of this post I suggest you focus on pre-pandemic years 2018 and 2019.

Monthly total patronage jumps up and down a fair bit in 2018 and 2019 (with higher totals for most 31-day months, who would have guessed?), but average school weekday patronage was relatively smooth across the year as you might expect. The average school week patronage data also shows clearly that March is the busiest month of the year. But if you looked at the monthly totals you might draw the false conclusion that days in May are generally as busy as days in March (at least for 2018).

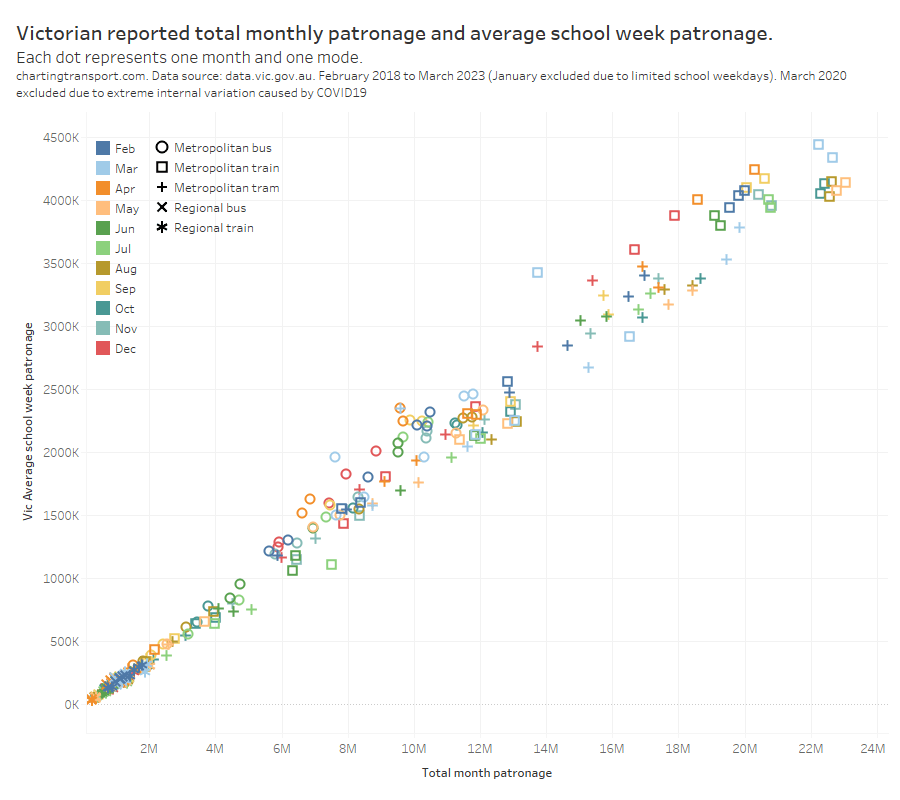

To further illustrate the differences, the next chart compares monthly average school week patronage to total monthly patronage, for all months February 2018 to March 2023 (excluding Januarys). Each dot is a mode and a month/year, and if total monthly patronage was as good a representation of patronage as school week patronage then this would need to be a fairly thin cloud as data points.

You can see the cloud is not very thin. March and April are often outliers, as they are subject to shifting Easter and school holidays.

March 2020 is actually one of the biggest outliers – as it was also when Melbourne first went into a COVID lockdown.

Another common form of analysis in recent (pandemic) times has been to compare monthly patronage to the same month in (pre-pandemic) 2019, to get an indication of patronage recovery. The following chart shows patronage relative to 2019 using both total monthly patronage and average school week patronage for Melbourne’s public transport:

You can see the orange line (total monthly patronage) is prone to bouncing around month to month, while the blue line (average school week) generally shows a smoother trend. Someone not knowing any better might have been slightly alarmed or confused about the steep decline in total monthly patronage recovery in October 2022, whereas on the average school week measure it was only a slight drop on September 2022 (perhaps because of planned disruptions to the network?).

Total March 2023 Melbourne public transport patronage was 78.8% of the total in March 2019, but 75.3% of the March 2019 average school week patronage. The total monthly patronage approach arguably overestimates the likely underlying patronage recovery by 3.5%.

How much noise gets introduced when analysing monthly totals?

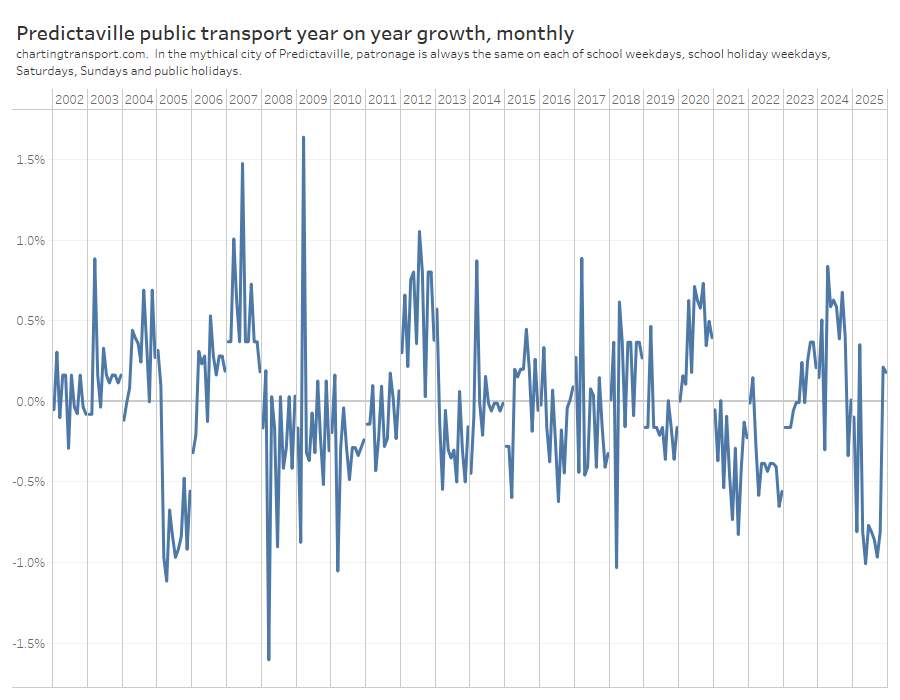

Let me introduce you to the mythical city of Predictaville. Nothing ever changes in Predictaville. There is no population growth, no behaviour change, no pandemics, no seasons, no illness. It’s very boring and entirely predictable.

Every school weekday there are exactly 440,000 public transport boardings, every school holiday weekday it is 340,000, every Saturday 195,000, Sunday 135,000, and public holiday 110,000. Remarkable round numbers, I know. It’s been like this since 2001 and all indications are that it will be like this until at least 2025.

These numbers just happen to be pretty similar to average Melbourne bus patronage in 2019, and Predictaville just happens to follow the Victorian school and public holiday calendar.

So public transport patronage growth in Predictaville is going to be exactly zero all the time, right?

That’s what you will get when measuring growth by average school weeks.

But what if you were measuring growth year on year using total monthly patronage?

According to this measure, patronage in Predictaville sometimes grows at +1.6% per annum and sometimes declines at -1.6% per annum. You might think 2012 and 2020 were growth years, while 2005, 2008 and 2021 saw declines. All misleading.

This is actually a chart indicating the sort of avoidable error introduced when you do analysis on total monthly patronage. We don’t need and shouldn’t have this sort of error in our analysis; particularly if it is going to influence policy decisions.

How is patronage data being reported in Australia and New Zealand now?

At the time of writing…

Transperth and Wellington’s Metlink only publish monthly totals, which is problematic, as explained above.

Transport for NSW publishes monthly total patronage which is likewise problematic.

They also have an interactive dashboard that effectively provides average weekday patronage, average school weekday patronage, and average weekend/public holiday daily patronage (but not average school holiday weekday patronage). Unfortunately you cannot download this data, and it doesn’t take into account that different months contain different numbers of Sundays, Mondays, Tuesdays, Wednesday, Thursdays, Fridays, and Saturdays. We know patronage varies by day of the week. Worse still, there is likely a significant difference between typical Saturday and Sunday patronage and different months might have 4 or 5 Saturdays and 4 or 5 Sundays. This means the average weekend daily patronage figures have avoidable misleading variations between months and years.

NSW have also published very detailed Opal data for selected weeks in 2016 and 2020 (only two were pre-pandemic school weeks), but no such data on an ongoing basis.

Transport Canberra reports average weekday and weekend daily boardings by quarter, but doesn’t distinguish school and non-school weekdays and bundles public holidays with weekends, which makes it very difficult to cleanly analyse growth trends. However they also publish daily data which is useful, but you need a calendar of school and public holidays.

The South Australian government reports quarterly Adelaide boardings (buried in a dataset about complaints) which is problematic as I’ve explained above. You can also get daily Metrocard validations by route (not quite the same as boardings), although exact numbers are not reported – just bands in multiples of 10, which makes it pretty much impossible to sum to estimate total daily patronage.

Translink (south east Queensland) publishes weekly passenger trip counts (to 2 decimal places!), which is slightly better than monthly, but analysts still need to have their own calendar of school holidays or public holidays to make sense of variations week to week. And at the time of writing data unfortunately hadn’t been updated since October 2022.

Auckland publishes monthly and daily patronage figures which is very handy. The daily data allows you to construct average school week patronage, but you need a calendar of school and public holidays.

So my plea to all agencies is to consider publishing average daily patronage by day type and day of the week, as Victoria now does. This will enable external analysts to do cleaner patronage analysis with much less effort. Perhaps an organisation like BITRE could even compile a national database of such data.

Even better would be for agencies to also publish daily patronage estimates, along with a day type calendar including school and public holidays, which would enable analysts to do even more with the data.

Can we do even better for patronage reporting and analysis?

Average patronage by day of the week and day type avoids much of the misleading variations in total monthly patronage data, helping us to better understand underlying trends.

But there will still be other smaller sources of misleading variations and you could definitely take this further, for example:

- Filter out Mondays next to a Tuesday public holiday and Fridays next to a Thursday public holiday, as these are popular days for workers to take leave to create a long weekend.

- Likewise, filter out weeks with more two or more public holidays falling within Monday to Friday – which are also popular times to generate longer holidays with fewer annual leave days.

- Filter out the first / last weeks of the school year if some schools follow a slightly different calendar (particularly in New Zealand). I discarded January above partly for this reason. All Decembers (in Australia at least) will also be impacted by senior students finishing school earlier, but the impact might vary year to year.

- Filter only for weeks where both school and most universities are teaching (although that leaves you with only about six months of the year, plus not all universities follow the same academic calendar).

- Filter out any days with free travel or large-scale disruptions (planned or unplanned). For example, free travel is usually offered on New Year’s Eve and Christmas Day in Victoria. And Sydney had several free travel days following major unplanned disruptions in 2022.

- Filter out Saturdays and Sundays on long weekends and during school holidays, which are probably more likely to be impacted by larger scale planned disruptions.

I mentioned at the start of this post that variations in Sydney monthly total patronage recovery figures were misleading, and hopefully you now understand why. In an upcoming post I’ll estimate underlying patronage recovery across big cities in Australia and New Zealand, and explain why I think actual underlying patronage recovery in Sydney didn’t change so much between March and April 2023.

Posted by chrisloader

Posted by chrisloader