Motor vehicle ownership has a strong relationship with private transport mode share, and has recently seen declines in some Australian cities (e.g. Melbourne). In addition, we know that younger adults more recently have been deferring the acquisition of a driver’s licence (see: Update on Australian transport trends (December 2020)), so have they also been deferring motor vehicle ownership? For which age ranges has motor vehicle ownership increased and decreased? How might this have influenced journey to work mode shares? And how do changes in motor vehicle ownership relate to changes in driver’s licence ownership?

This post aims to answer those questions for Australia’s six largest cities, primarily using 2011 and 2016 census data, but also using household travel survey data for Melbourne.

But first…

A quick update on motor vehicle ownership trends in Australia

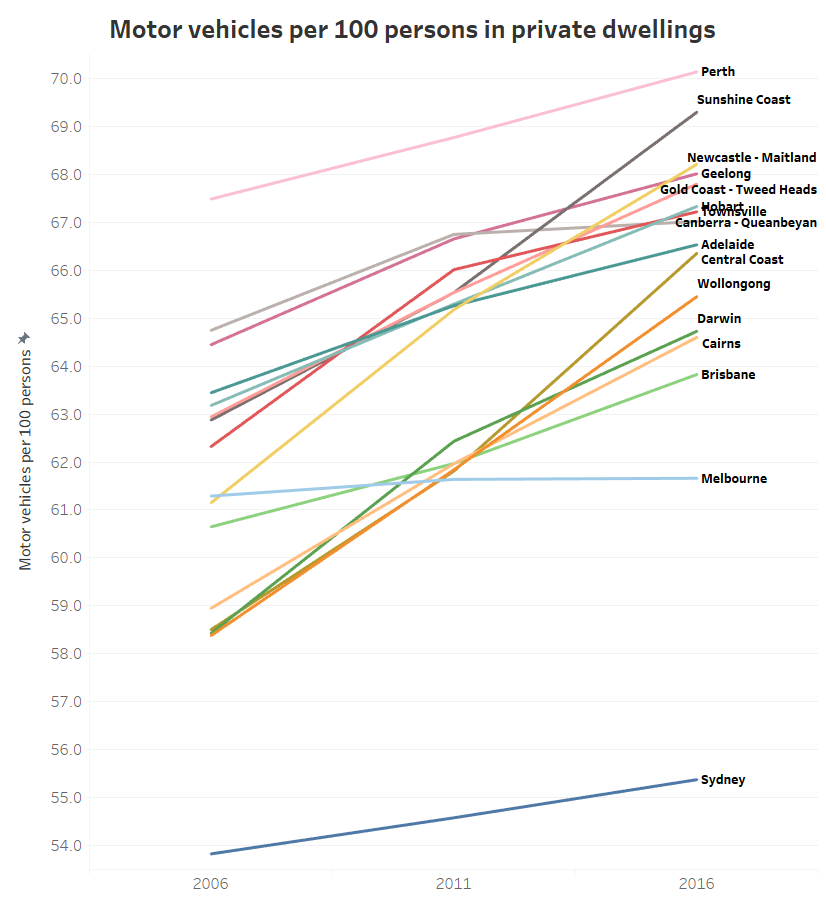

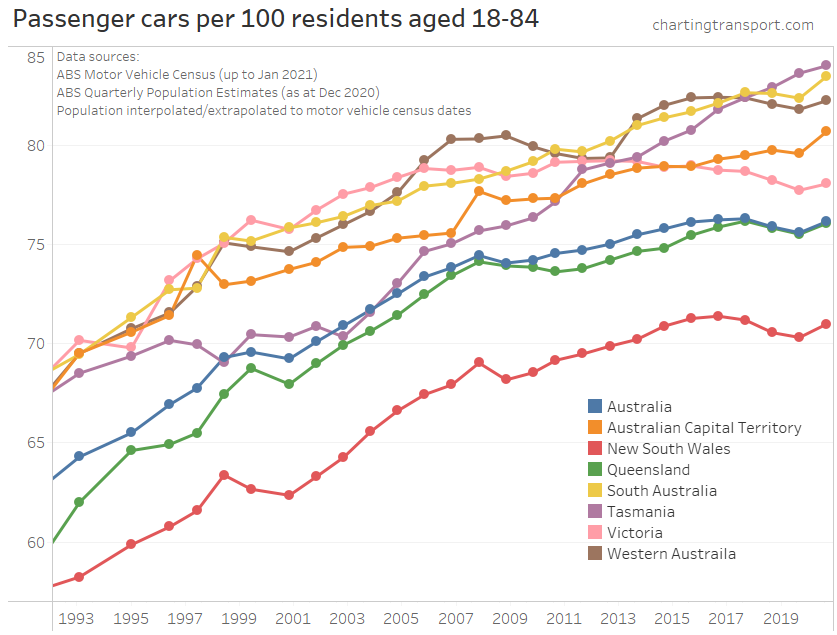

As I was writing this post, ABS released data for their Census of Motor Vehicle use – January 2021 (sadly the last motor vehicle census run by the ABS). I’ve matched this up with the latest available population data, and found a small but significant uptick in motor vehicle ownership rates in all Australian states in 2021 following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic:

I suspect this uptick will be at least partly due to a massive reduction in immigrants into Australia – who I’ve recently found to have much lower rates of motor vehicle ownership for the first few years they live in Australia (see Why were recent immigrants to Melbourne more likely to use public transport to get to work?) and also probably low motor vehicle ownership – see How and why does driver’s licence ownership vary across Sydney?).

It could also reflect a mode shift from public to private transport, as people seek to avoid the perceived risk of COVID-19 infection on public transport.

But there’s another likely explanation of this uptick and it relates to ages, so keep reading.

What does household travel survey data tell us about motor vehicle ownership by age in Melbourne?

My preferred measure is the ratio of household motor vehicles to adults of driving age (notionally 18 to 84).

Using Melbourne household travel survey data (VISTA), I can calculate the average ratio by age group pretty easily, and the following chart also breaks this down for parents, children, and other people (living in households without parent-children relationships):

With 2-year age bands there is a limited span of age ranges for some categories due to the small survey sample sizes (I’m only showing data points with 400+ people). So here is a similar chart using 4-year age bands, which washes out some detail but provides values for wider age ranges:

You can see some pretty clear patterns. Motor vehicle ownership was high for households with children (peaking for ages 12-13), parents – particularly in their late 40s, and those aged in their 50s and early 60s in households without children. Average motor vehicle ownership was lowest for young adults living away from their parents, and for those in older age groups.

Unfortunately the VISTA dataset isn’t really big enough to enable significant analysis of changes over time – the sample sizes for age bands get too thin when you split the data over years or even groups of years. I’d like to understand changes over time, so…

What can census data tell us about motor vehicle ownership by age?

Unfortunately it’s not possible to calculate the ratio of household motor vehicles to adults using Census (of Housing and Population) data (at least when using ABS Census TableBuilder).

The numerator is pretty easy for the 2011 and 2016 censuses which classify private dwellings as having zero, 1, 2, 3, 4, …, 28, 29, or “30 or more” motor vehicles. Only a very small number of households report 30+ motor vehicles. Unfortunately the 2006 census’s top reporting category is “4 or more” motor vehicles which means you cannot calculate the motor vehicle ratio for many households.

My preferred denominator – the number of adults of driving age – is not available in ABS’s Census TableBuilder. The closest I can get is the “number of persons usually resident” for dwellings – and private dwelling are classified as having 1, 2, 3, 4, 4, 5, 6, 7, or “8 or more” usual residents in the 2006, 2011 and 20216 censuses. Obviously I cannot calculate the ratio of motor vehicles to usual residents if there were “8 or more” usual residents.

(For the census data nerds out there: I tried to get a good guess of adults by using family composition, but it can only distinguish parents (who may or may not be of driving age), children under 15, and dependent students aged 15-24. And worse still, that doesn’t work for multi-family households, and you cannot filter for single family households as well as distinguish family types.)

So I’m stuck with household motor vehicles per person usually resident. And an obvious drawback is that motor vehicle ownership will be lower for adults living in households with children, compared to those without children.

Here’s the distribution of motor vehicle : household size ratios for Greater Melbourne for 2011 and 2016 (I’ve left out 2006 because too many households cannot be calculated). There are a lot of different ratio values, but only about a dozen common ratios, several of which I have labelled on the chart.

Sure enough, there were much lower ownership ratios for children’s households, and adult ages where children were more likely to be resident (generally mid-20s to around 60). Higher ratios peaked for people in their early 60s and then steadily declined into older ages, with most people in their 90s living in dwellings with no motor vehicles (if they are not living in non-private dwellings). For adults in their 60s, one car per person was the most common ratio.

I can also calculate the average motor vehicle ownership ratio for each age as an aggregate statistic (excluding 3-4% of households where I don’t know the precise number of residents and motor vehicles). Here’s how that looks for 2011 and 2016:

As mentioned, I cannot calculate this ratio for households where I don’t know the precise number of both motor vehicles and usual residents (or where I don’t know the number of usual residents, but do know there were zero motor vehicles). Across Australia’s five biggest cities that’s 4.1% of population in the 2016 census, 3.4% in 2011, and 10.4% in 2006 (but much higher proportions of younger adults). They sound like small numbers, but aren’t that small when you consider the shifts in ownership between censuses.

But there is another way to classify households with fewer unknowns – whether they have:

- no motor vehicles;

- fewer usual residents than motor vehicles; or

- at least one motor vehicle per usual resident.

The benefit of this approach is that you can classify almost half of the households where you cannot calculate an exact ratio:

- If a household had 30+ motor vehicles (very rare) but fewer than 8 usual residents, then it had at least one vehicle per person.

- If a household had 4+ motor vehicles (quite common in 2006 census) and 4 or fewer usual residents, then it had at least one vehicle per person.

- If a household had 8+ usual residents (about 1.3% of population in 2016), but 7 or fewer motor vehicles (93.5% of the 1.3%), then it had less than one vehicle per person.

Across Australia’s biggest five cities I can now classify all but 2.5% of the 2016 population, 2.3% of the 2011 population and 6.1% of the 2006 population.

The next chart shows the distribution of this categorisation for Melbourne (using Melbourne Statistic Division for 2006, and “Greater Melbourne” for 2011 and 2016). I’ve put the remaining people living in uncategorisable households (“unknown”) in between 0 and <1 motor vehicles per person, as it is likely households who did not answer the question about household motor vehicles probably had few or no motor vehicles (refer to the appendix at the end of this post for more discussion).

I have also removed people who did not provide an answer to the usual residents question (hoping they are not overly biased – they are probably households who didn’t respond to the census), and non-private dwellings (where motor vehicle ownership is not recorded).

The patterns are similar to the previous chart, with a double hump pattern of 1+ motor vehicles per person. There are some changes over time, which I’ll discuss shortly.

Unfortunately the unknown band is still pretty wide in 2006 – in fact I still cannot categorise around 15% of 20 year olds in 2006 (many must have lived in households with 4+ motor vehicles), so it doesn’t really support good time series evaluation between 2006 and 2011.

So how has motor vehicle ownership by age changed over time in Melbourne?

Many of the previous charts were animated over 2-3 censuses but there’s a lot of take in with different lines moving in different directions for different age groups. To help to get better sense of those changes, what follows are a set a static charts, and then some discussion summarising the patterns.

Firstly, the change in average motor vehicles per usual resident for each age year (but only for households where the exact number of motor vehicles and usual residents is known):

Secondly, here’s a static chart that shows the proportion of population living in households known to have 1+ motor vehicles per person for both 2011 and 2016 for Melbourne, and the difference between 2011 and 2016 (I’ve excluded 2006 as there were too more unknowns). I haven’t removed uncategorisable households from the calculations, on the assumption they bias towards lower motor vehicle ownership (as discussed above).

This chart shows very little change for children under 18, but also very few such households had 1+ motor vehicle per occupant in 2011 or 2016 so it’s not a very useful metric. Lower ownership ratios are much more common for households with children, so here’s a chart showing the proportion of the population living in dwellings with at least 0.5 motor vehicles per person, and the change between 2011 and 2016: (I used equivalent rules to classify households with 8+ usual residents or 30+ motor vehicles, where possible)

And finally, here’s a chart showing the proportion of the population living in dwellings reported to have no motor vehicles (probably an underestimate as I think many “not stated” responses are likely to be zero motor vehicles).

Each of these charts paints a similar picture. Here’s a summary by age ranges:

| Age range | Motor vehicle ownership trend |

| 0-17 | Slight increase |

| 18-26 | Certainly a decline, including around 1-2% more people living in dwellings with no motor vehicles. |

| 27-45 | Small decline of around 2-3% living in households with 1+ or 0.5+ motor vehicles per person. But there was no significant increase in households with no motor vehicles, and average motor vehicles per person was relatively stable. |

| 46-64 | Very small decline (around 1%) of people living in households with 1+ and 0.5+ motor vehicles per person, but little change in households without motor vehicles. |

| 65+ | Significant increase in metrics of motor vehicle ownership, and a significant decline in dwellings without any motor vehicles. |

So while overall motor vehicle ownership in Melbourne declined between 2011 and 2016, it was mostly in working aged adults, partly offset by family households and older adults increasing their rates of motor vehicle ownership.

And going back to the uptick in motor vehicle ownership in January 2021… recent immigrants to Australia have skewed towards young adults (particularly through skilled migrant visas). The massive reductions in immigrants in 2021 will mean the population contains proportionately fewer young adults – who generally have low car ownership, particularly recent immigrants. This slightly but significantly smaller number of young adults will no longer be fully offsetting those over 70 who are increasingly retaining motor vehicles longer into their life.

What about other Australian cities?

As above, I’ll present a series of charts showing the various metrics then summarise the trends.

Firstly, a chart showing the average ratio of motor vehicles per resident by age for all cities between 2011 and 2016 – for private dwellings where the exact number of vehicles and usual occupants is known:

To help see those changes, here is a static chart showing the change in average motor vehicles per person by age (I’ve used three-year age bands as the data otherwise gets a bit too noisy):

Here’s an animated chart showing the percentage of people living in private dwellings with 1+ motor vehicle per person:

There’s a lot going on in that animation (and the data gets a bit noisy for Canberra due to the relatively small population), so next is a chart showing the difference in population living with 1+ motor vehicles per usual resident:

As before, the threshold of 1 motor vehicle per person is not useful for examining the households of children, so here’s a similar change chart for the 0.5 motor vehicles per person threshold:

These difference charts mostly form duck-shaped curves with a slight increases for children, a mixture of increases and decreases for working aged adults, and a large increase for older adults (particularly for those in their 70s).

For young adults (18-30), motor vehicle ownership mostly declined in Melbourne and Canberra, but for Perth and Adelaide there was a large increase in ownership for those aged 21-39.

There was less change in ownership for those aged 40-54. On the metrics of proportion of population with 1+ and 0.5+ motor vehicles per resident there was a small decline in all cities, but for average motor vehicles per person, some cities declined and some increased. So perhaps the amount of variation in motor vehicle ownership narrowed in this age range.

Melbourne was mostly at the bottom of the pack, with Brisbane, Adelaide or Perth mostly on top.

To continue this analysis, I want to know whether these changes in motor vehicle ownership might be impacted mode share, but first we need to look at…

How did journey to work mode shares change by age?

Here are public transport mode shares of journeys to work by age for Australia’s six biggest cities, 2006 to 2016:

Public transport mode shares were much higher for younger adults in all cities in all censuses. Most cities rose between 2006 and 2011, but then different cities went in different directions between 2011 and 2016.

Here’s the mode shift between 2006 and 2011:

Most cities and ages had a mode shift towards public transport, particularly for those aged around 30, but less so for young adults.

Here’s the mode shift between 2011 and 2016:

Between 2011 and 2016 there was a mode shift to public transport in most cities for people in their 30s and 40s, but for younger adults there was a decline in public transport mode share in most cities, with only Sydney, Melbourne, and Canberra seeing growth.

However we are talking about motor vehicle ownership, and declining motor vehicle ownership may be because of mode shifts to walking, cycling, and/or public transport. So it is worth also looking at private transport mode shares (journeys involving private motorised modes but not public transport modes).

To help see the differences, here is the mode shift for private transport 2006 to 2011:

There’s a similar curve for all cities, but different cities are higher or lower on the chart. There was a shift towards private transport for young workers, a shift away in most cities for those in their 20s and 30s, and smaller shifts for those in their 40s and 50s

And from 2011 to 2016:

Again similar curves across the cities, with younger adults again more likely to shift towards private transport in most cities, a big shift away from private transport for those in their 30s and early 40s in Sydney and Melbourne, and smaller shifts for those in their 50s and 60s.

What’s really interesting here is that the mode share and mode shift curves are similar shapes across most cities (except the much smaller city of Canberra). There are some age-related patterns of travel behaviour change consistent across Australia’s five biggest cities.

How did changes in motor vehicle ownership compare to changes in private transport mode share?

If motor vehicle ownership increases you might expect an increase in private transport mode shares, and likewise you might expect a decrease in ownership to relate to a decline in private transport mode shares.

Indeed when you look at cities as a whole, there is generally a strong relationship between these measures, although different cities moved in different directions between 2011 and 2016.

In this post I’m interested in shifts for people in different age groups. The following chart shows the changes in motor vehicle ownership and private transport mode shares for each city and age group: (note different axis scales are used in each row of charts)

However I’m particularly interested in the change in these factors, rather than where they landed in each of 2011 and 2016. So the following chart plots the change in motor vehicles per 100 persons and the change in private transport mode share of journeys to work between 2011 and 2016 for five-year age bands (noting that of course every living person got five years older between the censuses).

That’s a busy chart but let me take you though it.

There’s one mostly empty quadrant on this chart (top-left): for no city / age band combinations did motor vehicle ownership decline but private transport mode share increase, which isn’t really surprising.

But in city / age band combinations where motor vehicle ownership did increase there there wasn’t always an increase in private transport mode shares – quite often there was actually a decline. So increasing motor vehicle ownership doesn’t necessarily translate into higher private transport mode shares – for journeys to work at least. Perhaps increasing affordability of motor vehicles means more people own them, but don’t necessarily switch to using them to get to work.

The largest declines in private transport mode share occurred in city/age band combinations that actually saw a slight increase in motor vehicle ownership.

The cloud is quite spread out – which to me suggests that motor vehicle ownership is probably not a major explanation for changes in mode share between 2011 and 2016 – there must be many other factors at play to explain changes in mode shares across cities. Indeed, see my post What might explain journey to work mode shifts in Australia’s largest cities? (2006-2016) for more discussion on these likely factors.

What is the relationship between motor vehicle ownership and driver’s licence ownership?

As I’ve previously covered on this blog (eg see: Update on Australian transport trends (December 2020)), data is available on the number of licenced drivers by different age groups, but only at the state level.

I’d prefer not to be using state level data as city and country areas might wash each other out, but I’d don’t have a lot of choice because of data availability. (Licencing data is available at postcode resolution in New South Wales (see How and why does driver’s licence ownership vary across Sydney?), but unfortunately you cannot disaggregate by both geography and age.)

Here’s another (busy) chart showing the relationship between licence and motor vehicle ownership by age band and city, across 2011 and 2016:

The main thing to take away here is that most of the points are within a diagonal cloud from bottom-left to top-right – as you might expect: there is less value having a driver’s licence if you don’t own a car, and little point owning a car if you don’t have a licence to drive it. The exceptions to the diagonal cloud are mostly age bands 30-39 and 40-49, where the average motor vehicle ownership rates are lower because many of these people often have children in their households, and I cannot remove children from the calculation using census data.

But I can control for the issue of children by going back to city geography by using household travel survey data for Melbourne (VISTA, 2012-2018). The following chart shows the relationship between average motor vehicle and driver’s licence ownership for adults by different age brackets.

The data points again generally form a diagonal cloud as you’d expect. Higher motor vehicle ownership generally correlates with higher licence ownership.

The change in ownership rates by age are interesting. Children under 10, on average, lived in households where adults have very high levels of motor vehicle and licence ownership. Licence ownership was slightly lower for adults in households with children aged 10-17 (although this could just be “noise” from the survey sample). Young adults (18-22) then on average lived in households with relatively low motor vehicle and licence ownership. As you move into older age brackets licence ownership increased, followed by increases in motor vehicle ownership, with both peaking again around ages 40-69 (although not as high as households with children). Those aged 70-79 and 80+ then had significantly lower rates of licence and vehicle ownership, as you might expect as people age and become less able to drive. These patterns are fairly consistent with the census data scatter plot, except for the key parenting age bands of 30-39 and 40-49 where the census data analysis cannot calculate ownership per adult (just per person).

How has licence and motor vehicle ownership been changing for different age groups?

Across Australia, licence ownership has been increasing in recent years for older adults (particularly those over 70), and declining in those aged under 30 in states such as Victoria, New South Wales and Tasmania (for more detail see Update on Australian transport trends (December 2020)).

The following chart shows state-level changes in motor vehicle ownership and licence ownership between 2011 and 2016 by age bands: (note different scales on each axis)

This chart also shows something of a direct relationship between changes in motor vehicle and licence ownership, with people aged 70+ having the largest increases in both measures (except for Victorians aged 80+ who saw a decline in licence ownership). Younger age bands often had a decline in licence ownership, even if motor vehicle ownership in their households increased slightly (on average). For those aged in their 40s, there was generally an increase in licence ownership but only small changes in motor vehicle ownership – including slight declines in most states.

Teenagers in the ACT were an outlier, where there was a significant decline in licence ownership between 2011 and 2016 that someone with local knowledge might be able to explain.

Overall the relationship between changes licence ownership and changes in motor vehicle ownership is not super strong. Increasing licence ownership does not automatically translate into increasing motor vehicle ownership. There must be more factors at play.

I hope you’ve found this post interesting.

Appendix: What about households where census data is missing?

The non-response rate to the question about household motor vehicles was around 8.4% in 2016 (up from 6.5% in 2011) and most of these were for people who did not respond to the census at all. Non-response was fairly consistent across age groups as the next chart shows. Quite a few people had a response to the question about number of usual occupants, but did not respond to the question about motor vehicles. Poking around census data, these people often:

- didn’t answer other questions;

- were less likely to be in the labour force;

- were generally on lower incomes;

- were more likely to be renting;

- were less likely to have a mortgage; and

- were more likely to live in a flat, apartment or unit, and less likely to live in a standalone/separate house.

So my guess is that they were less likely to have high motor vehicle ownership.

The number of “not applicable” responses increased significantly into older age groups, and I expect most of these will be people in non-private dwellings (e.g. aged care). I have removed people with “not applicable” responses for usual occupants and household motor vehicles as they are likely to be non-private dwellings.

The chart gets a bit noisy for ages above 100 as very few such people live in private dwellings.

Posted by chrisloader

Posted by chrisloader